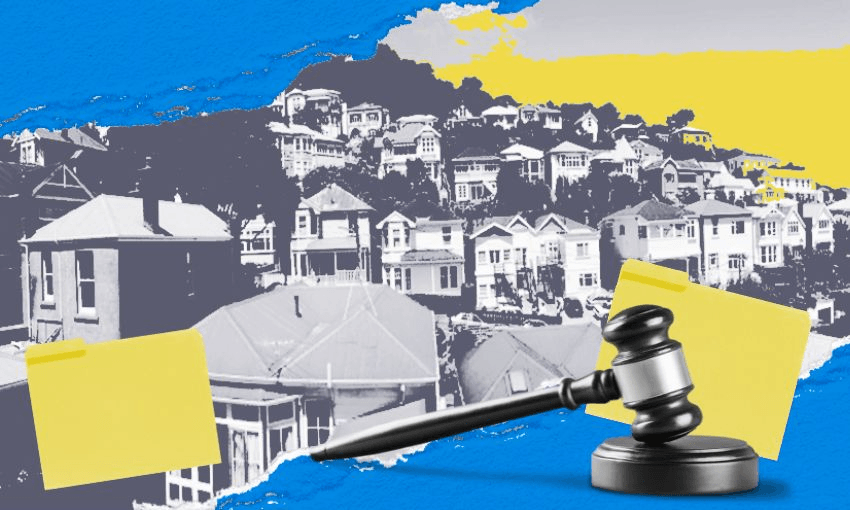

After the high court backed Wellington City Council’s decision to reduce the city’s character areas, Joel MacManus looks back at the five decades that shaped the restrictive housing policy.

The motorway came and tore the community in two. A great big gash of concrete. Eight lanes of destruction and separation.

Thorndon is New Zealand’s oldest residential neighbourhood; the place where the British occupation of Wellington city began. Then, Wellington Urban Motorway cut right through its heart.

The foothills motorway, as it was originally known, was first laid out in 1963 by an American consulting firm. By 1978, it was complete. Hundreds of homes were demolished, and thousands of bodies were dug up from Bolton Street cemetery and dumped in a mass grave.

Whether or not you believe the motorway was necessary – and many today would say it was – Thorndon was never the same. Arguably, Thorndon no longer exists as one cohesive area. The chunk on the city side of the motorway could more accurately be called Pipitea, and the other side is centred around Tinakori Village.

It wasn’t the first time this had happened, and it wouldn’t be the last. In the 1890s, entire blocks of Wellington were demolished in “slum clearance” because council authorities decided they had become so unsanitary that destruction was the only option. In the 2000s, the Inner City Bypass tore through the “bohemian” areas at the back of Te Aro, demolishing dozens more homes and changing the fabric of the community.

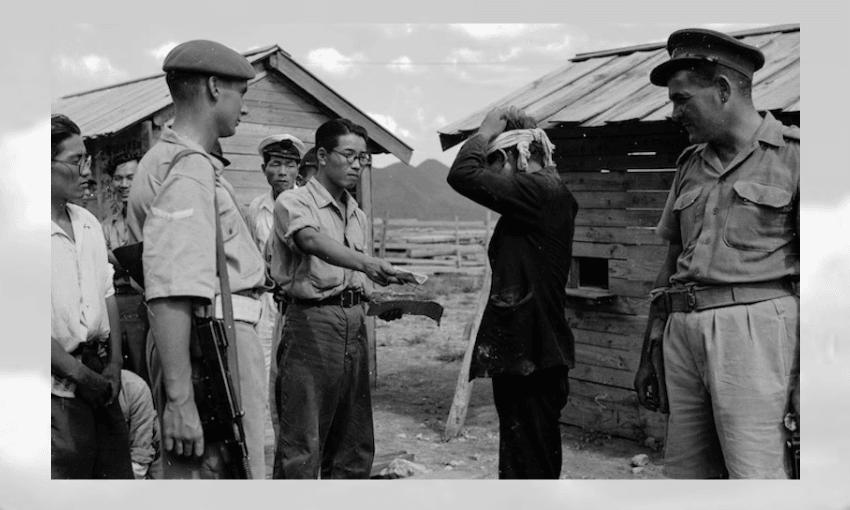

In the 1960s, the motorway construction faced years of protest from locals who correctly foresaw the damage it would do to their community. It was a time when change was in the air. The postwar boom had made cars financially accessible to the masses, and suburban living was the hot new thing. Cities around the world, trying to respond to the influx of traffic clogging their streets, embraced urban motorways as the future.

The hot new thing in city planning was modernism, which emphasised large-scale infrastructure, car-centric development, and top-down control to impose order and efficiency on chaotic urban environments.

The movement was exemplified by New York’s powerful planning commissioner Robert Moses. His most famous and controversial project was the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have demolished 416 buildings and the entire neighbourhood of Greenwich Village. What happened next has become part of the gospel of urban design.

Jane Jacobs, a journalist and activist with no formal qualifications in urban planning, started a campaign against the expressway. Her writing, most notably The Death and Life of Great American Cities, pushed back against Moses’ unsympathetic approach, advocating instead for human-scale design, vibrant streets, public spaces and the organic complexity of neighbourhood life. She viewed cities from the ground, while Moses saw them from a 30,000-foot view.

The modernists liked high-rise housing projects, separated from one another by wide roads and green spaces. Jacobs encouraged a great appreciation for older buildings and medium-density blocks, where everything was connected.

Today, Jacobs is known as “the mother of urban design”. Hundreds of cities around the world celebrate her birthday on May 4 by holding Jane’s Walks, volunteer-led walking tours that highlight interesting and overlooked parts of the city. Living Streets Aotearoa is hosting one in Wellington this weekend.

In response to the motorway construction and inspired by Jacobs’ ideas, Thorndon residents created the Thorndon Society to “protect and preserve” what remained of Thorndon. They organised walking tours in their area, installed information signs and plaques highlighting notable homes, and encouraged a renewed interest in neighbourhood character.

In 1974, Thorndon residents successfully lobbied Wellington City Council to create New Zealand’s first special character area: Residential E Zone, a five-hectare area centred around Sydney Street West. It was the remnant of an old residential gully that had been mostly wiped out by the motorway, filled with an interesting combination of grand wooden villas and small workers’ cottages.

It did not mean that every building within the zone was subject to heritage restriction, though some individual buildings are heritage-listed, including the Rita Angus Cottage. The intent of the Residential E Zone was purely stylistic; any alterations or new buildings had to be approved by the council to ensure they fitted within the existing architectural style. The Thorndon Society’s newsletters from the time, which are archived online, made it clear that “the zone was not intended as a museum zone and elements of change are inevitable”.

Gradually, though, the Thorndon Society’s ambitions grew. It opposed a new apartment building on Murphy Street, a new church on Hill Street, two townhouse developments on Grant Street, a doctor’s surgery on Tinakori Road, and several new offices.

Perhaps most egregiously, the society took Wellington City Council to the planning tribunal to stop a restaurant at 328 Tinakori Road (the site of the recently closed Daisy’s) from expanding to add 20 additional seats. In today’s eyes, this seems absurdly anti-business. But at the time, the society was operating from a position of fear. In the words of one newsletter writer: “Contemplate the amount of traffic that can be generated by the addition of 20 extra seats to an existing cafe, a takeaway food outlet, a childcare centre or a supermarket… increased traffic congestion lends argument for road widening and subsequent destruction of historic buildings.”

By 1989, the Thorndon Society was pushing to expand Residential E Zone to cover broader swathes of Thorndon. In the 1990s, a new generation of activists fought against the Inner City Bypass (including current city councillors Iona Pannett and Laurie Foon). The protesters took inspiration from the Thorndonites and the Jacobites, leading to a renewed interest in neighbourhood protection.

In the 2000 District Plan, Wellington City Council added character areas in Aro Valley, Berhampore, Mt Victoria, Mt Cook, Newtown, and more of Thorndon. Further additions were made in 2008 and 2011. These new character areas weren’t like Residential Zone E. They weren’t just focused on small, architecturally cohesive areas. They covered entire suburbs. And the legal restrictions were much stronger. No house built before 1930, regardless of condition or style, could be demolished without a resource consent, which meant neighbours had immense power to block new developments.

It seems no one realised just how vast the character areas had become until, in 2019, the NZ Herald’s Georgina Campbell reported that they covered 87.9% of land parcels in Wellington’s inner residential areas. Laurie Foon – now the deputy mayor – said she “felt really sick and stunned” when she saw the numbers.

The pushback against character areas was led by A City for People, a group of young activists closely tied to Generation Zero. They were part of the rising yimby movement (yes in my backyard). They believed rules preventing new housing developments (such as character areas) had played a key role in the housing crisis. A City for People started a campaign to eliminate, or at least seriously reduce, the character areas. For them, it wasn’t just about housing supply, but urban form – they wanted higher-density housing close to the city centre and train lines so people could live low-carbon lifestyles.

In the submissions on the council’s Spatial Plan in 2020 and District Plan in 2022, the yimbys were vastly outnumbered. But they convinced a majority at the council table to support their position. Marko Garlick’s submissions for Generation Zero and A City for People became the key piece of evidence the council used to reduce the areas covered by character restrictions from 306 hectares to 85 hectares. Housing minister Chris Bishop signed off the change last year, and the new District Plan became official.

Live Wellington, a group that supports character restrictions, launched a judicial review challenging the decision. On April 17, the high court backed the council and the minister’s decision. (Emma Ricketts wrote an excellent explainer of the case for Stuff.)

Bishop has signalled that his upcoming reforms to the Resource Management Act may make it more difficult for councils to create character areas – or even force councils to compensate homeowners if they impose rules preventing them from developing their property.

The yimbys won the battle and, with the political winds blowing in their direction, it seems likely that they’ll win the war. But I’m not sure they’ve ever truly understood their opponents.

Supporters of character areas have been accused of creating a supply shortage to boost their property values. But that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. If someone only cared about their property value, they would want their land to be more developable, not less. They’ve been accused of wanting to keep poor people out of their area, but that ignores the fact that character areas have some of the highest rates of renters. Others have suggested fans of character areas are simply old-fashioned conservatives who don’t want anything to change. But the people who fought the bypass and the motorway weren’t conservatives. They were progressives. The Thorndon Society had to defend itself against claims that it was an extension of the Labour Party.

Character areas were a well-intended policy, but they were a victim of their own success. The Jacobites successfully created a new appreciation for neighbourhood character and historic architectural styles. In the 1980s, cheap government-backed loans encouraged people to renovate old villas, and they did so en masse. The idea of “slum clearance” for new motorways fell out of fashion. Robert Moses is reviled, Jane Jacobs is beloved.

The policy problem that character areas were created to solve mostly no longer exists. But all solutions eventually beget new problems. In the case of character areas, they contributed to an inner-city housing shortage, high rents, urban sprawl and a generation of young people locked out of the property ladder.

We can, and should, recognise that people have powerful emotional connections to character areas and the wooden villas within them. But we should also recognise that cities must evolve, and that confronting the housing crisis necessarily requires change.