The violent deportation of migrants is not new, and New Zealand forces had a hand in such a regime after World War II, writes historian Scott Hamilton.

The world is watching the new Trump government wage a war against migrants it deems illegal. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials and police have dragged migrants from homes and streets and put them onto planes or into camps. Many have been denied due process. Seventy-nine years ago another American administration began a deportation programme, sending away tens of thousands of desperate migrants. But it was New Zealanders, not Americans, who were charged with hunting down and deporting them.

From 1946 to 1948, New Zealand soldiers and pilots were stationed in Japan’s Yamaguchi prefecture, at the southwest edge of Honshu Island. They were part of a Commonwealth force that also included Australians, Indians and Britons. Anxious to assert its relevance in the postwar Pacific, Britain had insisted that these forces share the job with Americans of occupying a defeated Japan.

New Zealand’s “Jayforce” consisted of 4,000 servicemen and a few dozen nurses. Most of them came from the army, but there were also 25 pilots and 250 air force support staff. Only narrow waters separate southwest Honshu from the large Korean port of Pusan, and the New Zealanders were quickly confronted by thousands of Koreans crossing the gap.

Japan seized Korea in 1910. Because they were subjects of the emperor, Koreans were considered Japanese nationals, and in the 1920s and 30s, hundreds of thousands were recruited to work in the imperial homeland. Although they faced discrimination, and could usually only secure low-paying jobs, they were free to move back and forth between Korea and Japan. The pre-war migrants had come willingly, but after Pearl Harbour, Japan became desperate for labour, and took slaves from Korea to mine coal and build weapons.

When Japan surrendered in 1945, it was hosting two and a half million Koreans. Many quickly repatriated themselves, commandeering ships from Honshu ports. But 600,000 Koreans opted to remain in Japan. Soon they were being joined by refugees from a hungry and violent Korea.

The Americans made their general Douglas MacArthur supreme ruler of postwar Japan and the southern half of Korea. In Japan, MacArthur established his own administration but retained national and local Japanese governments, getting them to implement his policies. After MacArthur declared the end of the Japanese Empire and the independence of Korea, both American and Japanese administrators expected Koreans in Japan to leave. For many Japanese Koreans, though, Japan had been home for decades. They had families, homes, and jobs or businesses in Japan.

For the defeated and humiliated Japanese, Koreans were a reminder of the empire they had lost. For MacArthur and his administration, Koreans were potential allies of the communist forces that already controlled the north of the peninsula. American hostility increased after South Koreans launched the Daegung Uprising against MacArthur’s rule in 1946. Demanding self-government, the Koreans staged a general strike and attacked US soldiers. The uprising simultaneously increased American suspicions about Koreans and sent refugees fleeing for the supposed safety of Japan.

MacArthur gave the job of overseeing the deportation strategy to Nicholas Collaer, who had worked for the US Border Patrol before running internment camps for Japanese Americans during World War II. Collaer was a xenophobe. In a 1949 article about his career, he called the US frontier with Mexico “ten thousand miles of trouble”, where a “human coyote” lurked. Collaer helped craft Japan’s Alien Registration Ordinance, which was modelled on wartime American legislation and required Koreans to register with authorities and carry special identity cards proclaiming their status as “aliens”. Koreans in Japan were banned from voting in the first postwar elections, and an American decree closed the ports of Japan.

When New Zealanders arrived in southwestern Honshu in 1946, they were immediately tasked with deporting Koreans and intercepting Korean ships headed for Japan. Ninety New Zealand troops were put in charge of Senzaki Repatriation Camp, a prison made from barbed wire and sheds on the waterfront of the port town of Kure.

New Zealand pilots worked with the Indian navy to try to intercept and force back vessels making the journey from Pusan to Honshu. Most of these boats were powered only by sails; migrants packed their decks and crammed their small holds. In her history of New Zealand’s air force, Margaret McClure describes “Corsairs with six machine guns swooping just a wingspan above the water” as they hunted for Koreans. Pilots “buzzed” the small migrant ships, trying to frighten them into reversing course. Ships that continued towards Japan were stopped, boarded, and towed into port. Their occupants were sent to Senzaki.

Photographs by New Zealanders show them leading long lines of Korean deportees from Senzaki camp to waiting American ships. Even the youngest and smallest migrants carry loads of belongings on their backs. Some deportees refused to go easily. In August 1946, New Zealand troops had to travel as guards on one huge ship taking 2,500 deportees to Korea. Reports in New Zealand papers explained that “mutinous” Koreans had threatened to take over the ship and turn it around.

Under New Zealand’s watch, conditions in Senzaki Repatriation Camp quickly deteriorated. In 1946 the camp’s population soared from 600 to more than 3,000. Food ran out, and the camp’s sheds were crammed with bodies. In the winter of 1946-47, cholera spread through Senzaki. Deportation became a death sentence for some of the camp’s captives.

The Trump administration claims illegal migrants come to rob Americans and spread diseases, but aid workers insist that most of them are motivated by poverty and desperation. The same was true for the Korean migrants who poured into New Zealand-occupied Japan. Commonwealth forces hired a Japanese Korean man named Cho Rinsik to interview the migrants and discover why they’d fled Korea. In his report, Rinsik that “80%” of them had “come to Japan on account of hard living and to procure food”. Rinsik said that better-off migrants wanted to recover “real estate, property, or savings in Japan”.

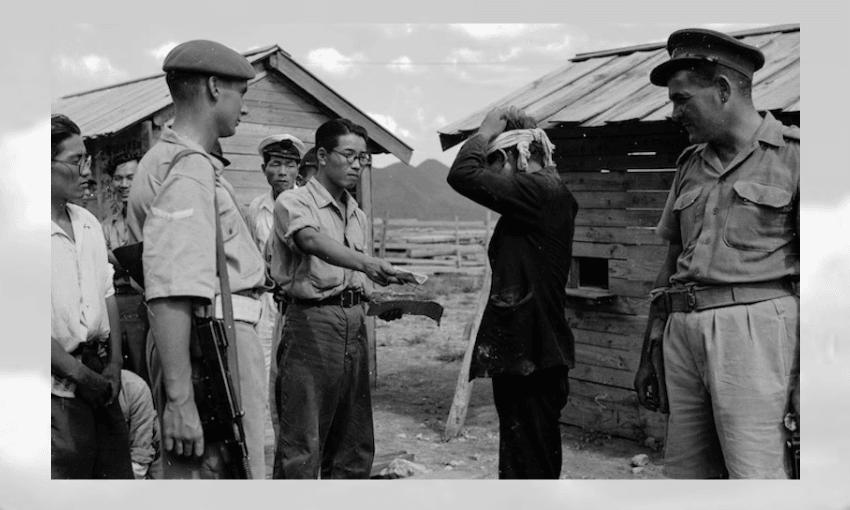

Koreans leaving Japan, whether voluntarily or compulsorily, could take with them only the paltry sum of 1,000 yen. A photograph in the Turnbull library shows a young Korean man tearing his hair in anger as a Japanese official confiscates a pile of banknotes from him. The man had been carrying 14,000 yen; he lost 13,000. Two New Zealand soldiers with rifles stand watching the confiscation.

Trump claims that migrants bring diseases and crime into America; media outlets like Fox News eagerly echo him. The same charges were made against Koreans in Japan by the American administration, and by newspapers in New Zealand. In October 1946, the Otago Daily Times claimed that Koreans were “spreading epidemics” in Japan and were behind “black market operations”. The Evening Star printed a disturbing photograph by a New Zealander showing a Korean mother and her small daughter being sprayed with the toxic chemical DDT at Senzaki camp. A caption by the photographer explained that they were being “deloused” under “New Zealand supervision”.

In 2025, communities threatened by deportation have organised and protested against Trump’s government. Californians cities have seen large anti-deportation marches. Koreans in Japan also organised and protested. In 1946, a League of Koreans was formed and spread through Japan, opening 300 branches in a few months. The League published a newspaper, opened Korean-language schools, and marched to demand equal rights.

When American and Japanese administrators banned Korean schools, the League staged huge protests. Photographs taken by New Zealand servicemen show crowds of Koreans protesting in southwest Honshu. Marchers carry Korean flags, and placards demanding the right to stay in Japan. In the city of Kobe, a march turned into a riot, as Koreans stormed a local government office and briefly held officials hostage. MacArthur responded by declaring a state of emergency and arresting thousands of Koreans.

In postwar Japan, the American administration used deportation as a way of punishing political dissent. In 1947, lieutenant-general John Hodge sent an official complaint to MacArthur about the number of Japanese Koreans being deported. Hodge claimed that the occupiers were deporting not just recent arrivals from Korea but “troublesome nationals” – Koreans who had lived in Japan for many years but who had protested American policies.

Elizabeth Ryan, who was a court reporter in Kobe, wrote that American authorities had issued orders to “arrest every last Korean” after the riot in that city in 1948. In the same year, Douglas Jenkins, the US Consul in Kobe, had estimated that there were “60 to 80 thousand Koreans in Kobe”, and called them “a low type” and “an alien group”.

In May 1947 a blaze destroyed the barracks of the New Zealand troops who ran Senzaki camp. It was the sixth suspicious fire at a New Zealand facility in six months. Some of the New Zealand troops suspected their work was being sabotaged. When questioned about the fires in parliament, defence minister Fred Jones said he was not sure whether they were deliberately lit or not.

New Zealand’s struggle with Korean migrants was reported extensively in our newspapers, but it has receded from memory, and has rarely been discussed by historians. In 2021, an article in NZ Army News remembered the mission to Japan, and mentioned that our troops deported “illegal migrants”. The tragedy is that those migrants only became illegal after the surrender of Japan and its occupation by the Allies. The end of World War II was supposed to bring peace and a better life in Japan, but for Japanese Koreans it meant becoming aliens in the country they had made home.