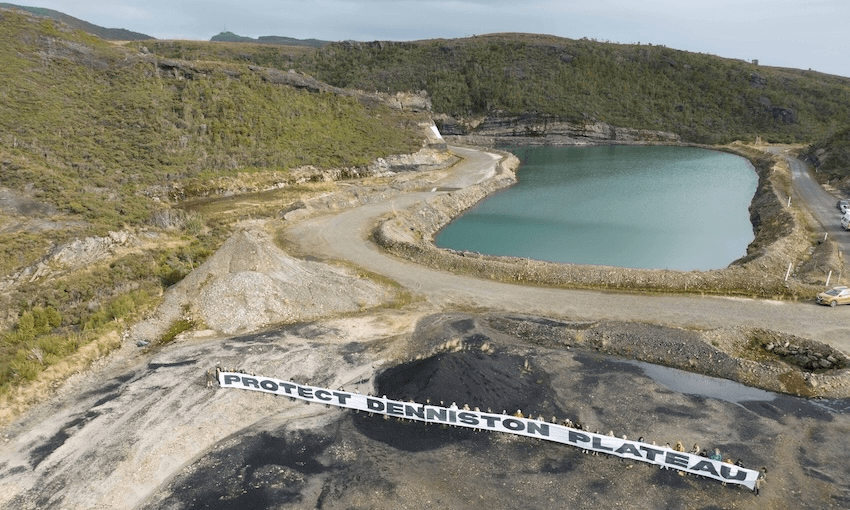

Coal mine expansion into the West Coast’s Denniston plateau attracted more than 70 protesters over the Easter weekend. Climate activists say this is only the first step in resisting the Bathurst mining company.

“Oh yeah – right there is where we’re digging trenches to keep tents from getting flooded,” said Adam Currie. It was April 19, Easter Saturday, and the climate activist was giving The Spinoff a tour (by video call) of an encampment on the Denniston Plateau. Seventy protesters were camping for the weekend on the remains of a coal mine, the proposed centre of an expanded mine project enabled by the fast-track legislation passed late last year.

It was hard to hear what Currie was saying over the wind. Two raincoated figures walked through a gazebo, the wall removed so it didn’t blow over. The screen pixellated; when it returned to focus, we were in the former coal mine office, abandoned since mining was suspended here in 2016. “We’ve just taken it over,” said Currie, pointing out a hand-drawn map. Illustrations of kiwi and lizards, then a red stain: the proposed mine site, flanked by bulldozers.

The Escarpment mine site is owned by Bathurst Resources, a mining company listed on the Australian Securities Exchange as BT Mining Limited. Beneath where the protesters were camping is 20 million tonnes of coking coal, which is used to make steel, mostly in India. According to Bathurst’s website, the mine requires “certain levels of production to be profitable” and its lifespan “depends on the coal market”. But as Bathurst told investors in October, the fast-track law, which allows infrastructure projects of national significance to bypass the resource consent process, means its mining permissions could become permanent, and will enable expansion of its existing mines.

“The emissions are crazy – big, bad, scary numbers,” said Rosie Cruickshank, one of the protesters at the encampment, wearing a burgundy raincoat and with hair escaping her ponytail in the wind. Using calculations from the Ministry for the Environment, it’s estimated that the coal produced by the Escarpment mine would generate 53 million tonnes of carbon dioxide. Combined with emissions from the Rotowaro mine in Waikato, which produces coal for domestic industrial use and is also approved as a fast-track project, Bathurst would be responsible for 66 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions over the period the mine is active. For comparison, the entirety of New Zealand produced 59 million tonnes of carbon emissions in 2022.

To the protesters, the proposed Denniston mine expansions represent everything wrong with the controversial fast-track law. “It really locks democracy out, it’s so ominous,” said Cruickshank. She gestured around her, the camera showing lush, dense bush broken up by dark land where the coal mine had been operating. “I’ve never seen bush like this before, I’m so grateful to have the opportunity to be here.” That the coal would be exported, for the profit of an Australian company, only makes it worse, Cruickshank said. “There are short-term benefits, but they’re not coming into our economy long-term. The gain is nothing compared to the climate crisis.”

Mining is often discussed as a vital part of the West Coast’s economy. “People do have the right to protest but what they’re doing is a health and safety risk. It’s affecting people’s working days and the company, what they need to produce, it’s just plain stupidity and grandstanding,” said Grey District mayor Tania Gibson, in comments reported by RNZ. “We’ve got about 1,200 new jobs from some of the [mining] initiatives that are being looked at on the coast at the moment.”

Of course, the views of the West Coast community are varied. “It’s humbling to see people from around the country spending their long weekend camping on a coal mine, instead of travelling,” Neil Silverwood, a West Coast local, told The Spinoff. He grew up getting to explore the “neat little caves” and forest on the Stockton plateau, which is now mostly a mining site. “We’ve lost access to the beautiful waterfalls and creeks,” he said, frustrated that he can’t share this with his young son. “The boom and bust cycle of mining is unsustainable, it’s done nothing for the West Coast.”

The encampment involved people from groups Climate Liberation Aotearoa and 350 Aotearoa, as well as other supporters. It’s part of a bigger campaign against Bathurst; 350 Aotearoa is also calling on ANZ to stop providing banking services to Bathurst and other fossil fuel companies.

Two days after talking to The Spinoff, Currie put those beliefs into practice. Along with six others, he climbed into the carts used to transport coal at Stockton, New Zealand’s biggest mine operated by Bathurst just north of Denniston. Seven climbers spent more than 60 hours in the coal carts, preventing coal from leaving the mine. Four people were arrested and 10 have been charged with trespass.

Resources minister Shane Jones criticised the protesters in a press release. “Mining brings in millions of dollars in royalties, and in wages and spending on infrastructure, plant and supplies. It is an industry with a proud history on the West Coast,” he said. “Businesses have a legal right, under a law passed by the New Zealand Parliament, to apply for fast-track approval. I’m confident in its robustness to ensure guard rails are in place for projects to ensure they comply with our environmental and conservation laws. These protesters should too.”

To Currie, the response was predictable. “His comments reflect a deeper truth: this government is doubling down on fossil fuels at the exact moment we need to be scaling up renewables,” he said. “We’ve stalled at least two days of coal extraction, sent a clear message to Bathurst and the government, and shown that people are ready to resist the Fast Track Act and the climate-wrecking projects it enables.”

The people resisting the expansion of the mine want it to become the poster child of the problems with the fast-track law: damaging to a vulnerable environment and the climate, putting native species at risk, the profits going offshore and the economic advantages uncertain. “There are 70 people here in the wind and rain, and it was essentially organised in secret,” said Currie on Saturday. “Imagine how many people will be angry about it once this project is public.”