Inundated with end-of-year lists, we all had big plans to do a lot of reading-for-pleasure over the holidays. Here’s where we ended up.

Despite the gazillion end-of-year reading lists and recommendations for the very latest books, summer is often a time for reading wildly. Whether it’s finally pulling a book, Jenga-style, from your to your to-be-read pile, or fossicking in the local Lilliput library, or making your way through the stack of NZ Geographic magazines at your aunty’s house – very rarely will summer reading adhere to crisp curation. And that is how gems are uncovered and lives changed.

Here, then, is what we managed to actually read over the holidays. We’d love to know what you read – go for gold in the comments (if you’re a member).

The Chthonic Cycle by Una Cruickshank

I somehow missed this when it was published in November and only picked it up after reading one of Una Cruickshank’s pieces in New Zealand Geographic. Tightly written, full of facts and definitely sparkly, the core of The Chthonic Cycle is a series of essays about different kinds of organic gems: jet, pearls, amber. From this starting point, Cruickshank leverages dozens of different threads that she stitches into beautiful wholes, taking surprising twists along the way. What do carved jet bears found in the graves of Roman babies say about attitudes towards childhood? Are the slats for rubbish to fall through in the Victorian Crystal Palace a metaphor for climate change? Who was the Quaker “Publick Universal Friend” who decided they were genderless in the eighteenth century? The answers to all these questions and more are in this delightfully-footnoted book, each essay containing, to borrow a term from one of Cruickshank’s sources, an immense world. / Shanti Mathias

Ghachar Ghochar by Vivek Shanbhag

Ah this weird little bitter pill of a story! Ghachar Ghochar, translated from South Indian language Kannada, is a novella that I read in almost one go on rainy Christmas Eve. It’s narrated by the son of a family whose fortunes have rapidly changed after their unmarried uncle starts a successful business selling spices. The uncle is the only character who seems to work; everyone else is at liberty to speculate wildly on each other’s personal lives. Is the dahl made by their uncle’s suspected lover more delicious than their mother’s? Why did the narrator’s sister run away from her expensively organised arranged marriage? And does the waiter at the coffee house know more about hallucinations of blood than he’s letting on? Meticulously observed, funny yet rancid, this is a story about wealth, family and the unsaid things that refuse to stay in the shadows. / SM

Take Two by Danielle Hawkins

Danielle Hawkins is one of New Zealand’s favourite romance writers for good reason: her rural, practical heroines experience the throes of passion and heartbreak, as well as juicy gossip and plates of scones. In this one, heroine Laura is adrift after finishing a lucrative government contract. She runs into the mum of her ex, Doug, and a series of so-unfortunate-they-might-be-unbelievable events lead her back to the farm where she once lived with Doug and his family. This time, Doug’s younger brother Mick is surprisingly grown up, and it’s amazing how feelings can bloom while dealing with flystrike, rescuing sheep from the swamp, reading children bedtime stories and having one’s good name besmirched at a funeral. Take Two is a lot of fun, a romance just as much about falling in love with a whole family as one brother or the other. / SM

Blue Blood by Andrea Vance

Sourced from the library of Toby Manhire, this was summer reading that was moreso summer homework to get myself up to standard on Aotearoa’s current political climate, and how we got here. In under 300 pages, Andrea Vance manages to sum up the years between the end of John Key’s reign as prime minister to the ascension of Luxon, leaving off with some speculation with how the 2023 election may pan out (simpler times). There’s some incredibly delightful (if pettiness gives you as much joy as it does me) comments from insiders and “unnamed senior MPs” in which some obviously bitter people are trying to get their just desserts. Delicious. / Lyric Waiwiri-Smith

Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead by Barbara Comyns

There is only one authority I trust in this world: Hera Lindsay Bird (and my editors). I was so amazed with her big-brained two-part ‘book for every year of your life’ series published last year that I made a promise to myself to check off all the recommended books for 24-year-olds before my next birthday, so I can officially be one of those really smart, well-read people (like Shanti). This Barbara Comyns classic is focused on a suicidal plague sweeping a small English town, where everyone seems to mostly hate each other. It’s the foulest book I’ve read, in language, setting and the way the characters just … are.

Did I enjoy it? That is a different question. It sticks like mud to your clothes and an odour of death in the air – one read through is more than enough. I’ve now regressed in age, and am reading one of the recommended books for 23-year-olds: Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer. This is much better. / LWS

The Love School by Elizabeth Knox

While reading this fantastic 2008 book of essays from Elizabeth Knox over summer, I dog-eared about a bajillion bits of advice to return to whenever I feel brittle and bad about writing (extremely often). For example: “The more personal the work, the more inclusive and unflinching. The less generalised it is to the experience of others, the more it is universally human.” Gah! Or this: “our only defence is having no shame.” Basically, if you see me oversharing big-time online this year, it’s wholly because of this advice. Beyond the writing wisdom, the book is packed with vivid accounts from Knox’s own life, including her time in the thick of the Springbok protests, golden childhood summers in Nelson and damp flats in Thorndon. A welcome peek into the inner world of one of our greatest ever of all time. / Alex Casey

Elaine Power’s Living Garden: An Illustrated Nature Diary by Elaine Powers

I love nothing more than unearthing a gem at a little free library, and over summer the Barrington Mall community nook provided a doozy in this truly beautiful book. After moving out to the countryside somewhere on the outskirts of Auckland, nature illustrator Elaine Powers spent an entire year from spring 1982 until spring 1983 chronicling the changes in her backyard. Capturing every day in both journal entries and stunning illustrations, this book was the perfect soothing read and a reminder to look the hell around you. Take this from December 1982: “I spent a quiet half hour sketching the pet baby Californian rabbits which were born three days ago. Nine soft little bundles of wrinkled skin with the tiny ears close to their heads.” / AC

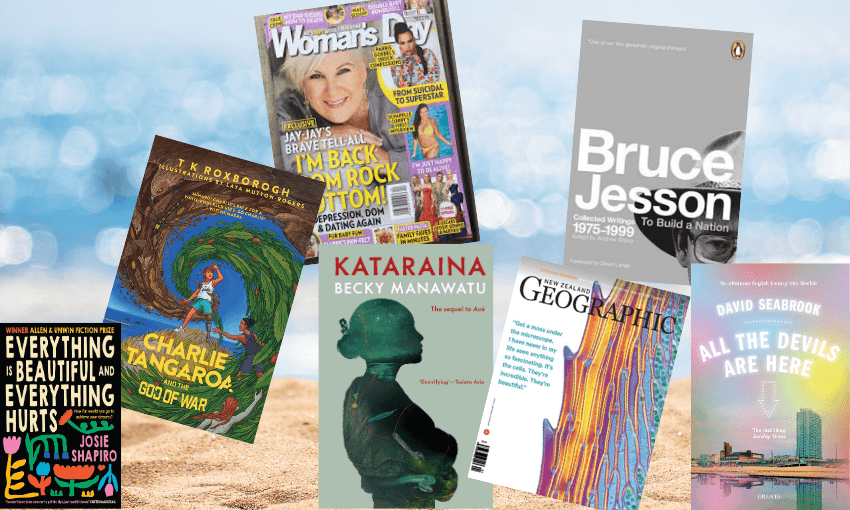

Everything is Beautiful and Everything Hurts by Josie Shapiro

I did not know this was a book about running, I just thought it had a pretty cover and was keen to read a fairly chunky novel. I ended up reading it in one big gulp and then lacing up my runners on Boxing Day (traditionally a day of rest). It was hard not to feel for little Mickey Bloom, with her splintering bones, short legs and big ambitions. The book is told in alternating chapters, half set in the present where Micky is running a marathon, and the other half telling her life story. Surprisingly, the parts about running aren’t boring and the coming-of-age narrative arc is not too predictable. The characters beyond Mickey sometimes feel one-dimensional, but this is a small complaint about a book I thoroughly enjoyed. / Gabi Lardies

Bruce Jesson: To build a nation (collected writings 1975 – 1999)

A book that’s been eyeing me down from my shelf since I found it at a school book fair last year. It’s a collection of Jesson’s columns and articles from 1975–1999 and I knew I should read it to get smarter and more knowledgeable about our recent past, but I wasn’t sure how fun it would be. I dipped in to find that Jesson’s writing is elegant, playful and understatedly insightful. So much of what he wrote about dear old Winnie holds up, like “Winston Peters created a constituency… of cranky, discontented and unforgiving people”, “His strength as a politician is that he has the ability to cause a sensation, but that does not make his simply a sensationalist” and “He invariably raises matters that are of real public concern, issues that other politicians are scared to deal with”. Some things never change, eh. / GL

New Zealand Geographic pretty much from front to back

I grabbed this along with a week’s worth of groceries for a New Year camping trip and it proved more popular than the cheese. I would throw it on the picnic blanket and some curious friend would pick it up, flick through and find something of interest. A story about moss perhaps, or the community at Lake Ellesmere/Te Waihora, or more bleakly, the great recycling delusion. We’d pawn off little “did you know”s to each other and feel like, while imperfect, at least the world is interesting. It’s the perfect read on hot summer days when books are just a bit too long and don’t have enough pictures. The truth is that the very few local magazines we have left are the créme of the crop, and hugely underrated. / GL

Woman’s Day Jay-Jay Feeney cover story

I acquired half a dozen books, all classics of some description, from the free community library thing near my house over the holidays, and got around to reading precisely none of them. Maybe one day I’ll get stuck into The Lying Life of Adults, Perfume, Man Alone, Being There, The Dice Man and whatever treasure I find in that upcycled dollhouse next. But this summer, probably the most substantial thing I read was the Woman’s Day cover story about how Jay-Jay Feeney has got back with her old flame Minou. Hard to find a novel as strange and compelling as this love story! / Calum Henderson

Kataraina by Becky Manawatu

The sequel to the much-lauded Auē hasn’t had as much hype as Becky Manawatu’s multi-award-winning, best-selling 2019 debut novel, but Kataraina is just as compelling. Just like Auē, there is darkness and violence here but there are also undeniable glimmers of hope that keep you turning the pages before it all gets too bleak. The narrative jumps between time periods and perspectives but Manawatu artfully weaves it all together. My favourite chapters were those centred around the kūkūwai, the wetland or swamp at the heart of the story that can’t be controlled or explained by anything in te ao Pākehā. I’d never heard of taramea before but reading Kataraina, I swear I could almost smell it. / Alice Neville

The Rural Hours: the country lives of Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Townsend Warner and Rosamond Lehmann by Harriet Baker

I’d hoarded this book for months. It’s a lovely hardback with fabric bindings and it has a photo of my favourite writer, Sylvia Townsend Warner, wading in a pond with a cigarette in her mouth on the cover. The book looks closely at the letters and diaries of the three women who in many ways defined literature in their time (and after) and how living in the country impacted their lives and work. Loved it. Made me wish for handwritten letters and to project myself into that time where the novel was a form still being turned around and new faces peered at. Fantastic writing, ideal Boxing Day transportation. / Claire Mabey

Charlie Tangaroa and the God of War by Tania Roxborogh

Set in Tolaga Bay, this novel (the second in the series) was high on my list for summer because Roxborogh’s writing is so clear and fluid it’s like being immersed in an East Coast lagoon. In this book, Charlie and his brother Robbie (who I love) are enmeshed with dodgy mining deals, feuding ātua, patupaiarehe and Charlie’s beautiful dad, Paketai (who is a ponaturi). Charlie is cool. Thanks to his dad he can hold his breath for ages under water and swim really well. The story is compulsive and political and will keep young readers engaged and old readers, like me, hooked. Perfect summer intrigue. / CM

All the Devils are Here by David Seabrook

I’ve had this book by my bed for about two years (I heard about it on Backlisted and then had to literally scour the world to find a copy of it – finally found a secondhand book dealer guy in Dorset who got a copy for me and posted it to my brother in London who brought it home with him one Christmas). It’s a collection of essays in which Seabrook weaves, effortlessly, information about dark characters who inhabit faded seaside towns in England, and his own meanderings in those places. He is a shadowy character in himself which makes the book feel like you’re entering into a den with a torch. If you’re into creative non-fiction you can’t get much better than this odd, dazzling, layered book. / CM