Before the Coffee Gets Cold by Toshikazu Kawaguchi opened the floodgates to a wave of cosy, melancholic Japanese and Korean fiction in translation. But what’s behind the popularity of these little books designed to give us big feelings?

@Grapiedeltaco can hardly speak through her tears. “Why would someone be crying over this book, bitch? I’m sad!” @sivanreads has mascara running down her face. “This book is not sad,” she sniffs. “And yet I feel the most insane, crippling sense of sadness in my chest that I don’t think will ever go away.” @Bootique2 is so distraught she struggles to squeeze the words out. “I didn’t finish the book. I can’t stop crying … Oh my god my eyes hurt! They deserved better… you guys were lying. My eyes burn!”

BookTok and GoodReads are strewn with the aftermath of Before The Coffee Gets Cold by Toshikazu Kawaguchi, first published in Japanese in 2015, and published in English in 2019 (translated by George Trousselot). The novel is nowhere near universally beloved (Sam Brooks published a lukewarm review on The Spinoff; and there are plenty of unimpressed responses between the exuberant five-star reviews on Good Reads; “so sickeningly sentimental, it’s almost unbearable” said Sam Quixote) but in the publishing trade it’s a bone fide smash hit.

Kawaguchi’s bestseller is set in a quaint back-alley cafe in Tokyo called Funinculi Funincula (more on that later) that bends the rules of space and time by allowing customers to visit the past, so long as they’re back before their magical coffee gets cold (an hour-ish). Encounters are ridden with loss, ennui and an opportunity to grapple with the idea that as much as we might want it to, the present can’t be changed by busting in on the past. There are four more books in the series – the latest one, Before We Forget Kindness, was published in 2024. Kawaguchi’s books have sold over six million copies and have been translated into over 40 languages.

Before the Coffee Gets Cold has regularly surfaced in the Unity Books Bestseller charts, published by The Spinoff, every year since 2019 (and didn’t leave the top ten for months in that year). In 2024, Kawaguchi appeared at the Auckland Writers Festival and spoke with journalist Maggie Tweedie, who observed that the Auckland audience seemed to strongly connect to his “ability to connect with grief; gently accept loss and move forward.” Melanie Taylor, who was Kawaguchi’s interpreter for the event, sat at the book signing table with him afterwards. It was so long that the queue stretched out the door and he was kept signing books for two hours. The people who came to the signing queue ranged in age, from early teens to seniors. “There were only two Japanese people,” said Taylor. “Many had read all of his books and were eagerly awaiting the next. Some shared [his books] helped them process losses and regrets.”

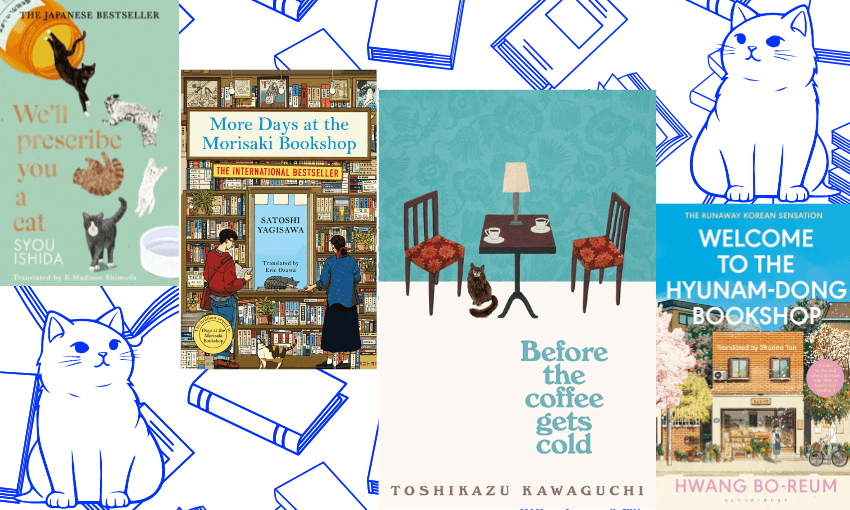

In Kawaguchi’s wake has marched a procession of similar novels: Days at the Morisaki Bookshop by Satoshi Yagisawa, Welcome To The Hyunam-Dong Bookshop by Korean writer Huang Bo-Reum, and the latest (published last week), We’ll Prescribe You a Cat by Siyu Ashida (one of many whimsical cat-related bestselling Japanese novels).

Mandy from Bookety Book Books confirms that for her bookshop, too, there’s been a marked increase in sales of this realm of heartstring-tugging translated fiction. “Before the Coffee Gets Cold was sitting on my bestseller chart towards the end of last year [2024] and we don’t always see backlist titles out performing new releases,” she says.

Each of the above titles was also a bestseller in Japan (or in Bo Reum’s case, Korea) before it was translated for an English-reading market. And each one features the hallmarks of what the publishing industry is calling “cosy” or “healing” fiction: quaint, bijou settings filled with books, cats and steaming mugs of time-travel coffee. The novels are written in an accessible style, are relatively short, and are designed to draw readers into a romanticised, domestic-adjacent world and take them far from the stresses of commuting, work, the encroaching mindfuck of AI, far right political agendas, genocides, billionaires, environmental catastrophe, and job losses. The emotionally loaded storylines often swerve hard into the sentimental and extract, at times, extreme emotional responses.

It’s far from uncommon in times of stress for people to turn to escapist art. The portal of story for relaxation has existed for as long as we have. But this particular moment of “healing” fiction – complete with snot and tear-soaked video responses that amass vast viewer numbers – suggests that readers around the world are not just in search of escape, but also catharsis. Japanese and Korean “healing” books are servicing a global demand for art that facilitates an almighty cry.

One origin for the melancholic tone of these novels can be found in Japanese literary criticism, in a concept called “mono no aware”, which roughly translates to “the pathos of things”, or feeling deeply about a thing. The idea is applied to art that is acutely aware of the poignancy of time passing, the impermanent state of life, of experience, of the senses. That everything is fleeting, and inherent in those moments is beauty as well as pain. It’s this undulation of feeling that underpins Before the Coffee Gets Cold and its specific peddling of tearjerking encounters.

But the closer you look, the more you can see shades of “mono no aware” in literature everywhere. The name of the cafe at the heart of Before the Coffee Gets Cold, Funiculi Funicula, references a song written by Luigi Denza with lyrics by Peppino Turce in 1880 to advertise the Vesuvius Funicular. The bouncy anthem has been made famous by a succession of artists including Pavarroti, Alvin and the Chipmunks, the Grateful Dead; and by its association with pizza (which also has origins in Napoli, where Denza and Turce are from). It may seem a curious name for Kawaguchi’s cafe, until you analyse the translation of the original Italian lyrics with “mono no aware” in mind:

I climbed up high yesterday evening, oh, Nannina,

Do you know where? Do you know where?

Where this ungrateful heart

No longer pains me! No longer pains me!

Where fire burns, but if you run away,

It lets you be, it lets you be!

It doesn’t follow after or torment you

Just with a look, just with a look.

It continues on for a few more verses in the same vein: pleading for Nannina to travel up the mountain, escape, and eventually be married. It’s yearning and romantic but full of potential heartache and missed opportunities. It’s a cosy song with a sly aim to meddle with your emotions if you’re so inclined (we don’t find out if Nannina says yes). It’s laden with the principle of what goes up must come down.

Kawaguchi’s reference to this old-school Italian banger suits the homey melancholy of his story. It’s easy to see why millions of readers have plucked this novel from the galaxy of books available to them and turned it into one of the brightest stars. But at the same time there is something profoundly, ironically sad about it. What is it about our lives that so many of us are seeking nostalgia and sentimentality in our art, and will go back again and again for more of the same medicine? (Like BookTok’s @sivanreads, who, in a post after her mascara-smeared one, tells her hundreds of thousands of followers that she’s going back in, again and again, hoovering the whole series, even gripping the Japanese edition of the latest book raking it for signs of emotional triggers even though she can’t understand a word.)

It’s also an irony that cosy fiction elevates bookshops and libraries and cafes just as the real life spaces are in serious trouble. Bookstores in Japan are in decline; in the UK (where cosy Japanese and Korean books in translation are incredibly popular) libraries have long been under attack from budget cuts; just as they have been in Aotearoa, too. Let’s not get started on the challenges facing the coffee trade.

The rise of “healing” fiction in translation is in many ways an easy phenomenon to explain. People under pressure need escape, catharsis and emotional connection. Another contemporary publishing phenomenon, “romantasy”, offers a similar sort of relief in the form of horniness, dragons and leathers. But these publishing phenomena also beg some questions: When won’t we need “healing” books? What is art meant to do in times like these? Is it even OK to escape? And what’s on the other side of the trend?

The International Booker Prize longlist for 2025 was announced this week. Among the list of all first-time novelists is Under the Eye of the Big Bird by Japanese writer Hiromi Kawakami, translated by Asa Yoneda. The novel is set in a distant future where humans are living in small tribes under the care of the Mothers. “Some children are made in factories, from cells of rabbits and dolphins; some live by getting nutrients from water and light, like plants. The survival of the race depends on the interbreeding of these and other alien beings – but it is far from certain that connection, love, reproduction, and evolution will persist among the inhabitants of this faltering new world,” reads the blurb.

The Booker Prizes calls Kawakami’s novel “an astonishing vision of the end of our species”. It sounds brilliant. Disturbing, alarming and challenging. Not at all cosy and far from healing. It’s a reminder that there’s an entire, exciting body of contemporary literature that English-language readers are missing out. Cosy fiction has pushed the door open for more novels in translation – but when the crying is over, we’re going to need the confronting books and visionary authors in great numbers, too.