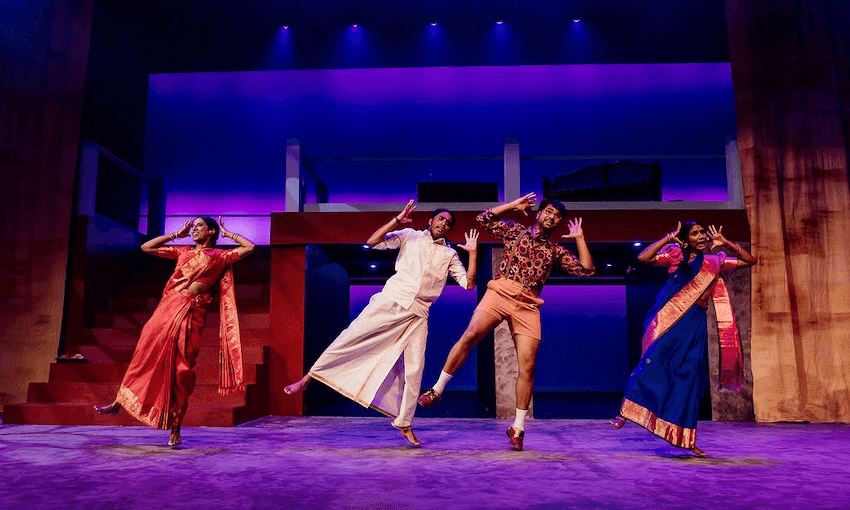

The third of Ahi Kurnaharan’s ‘epic trilogy’ of plays is beautiful to look at and listen to.

Can the songs we listen to tell us stories about our lives? This is essentially the premise of A Mixtape for Maladies, a show currently playing at the ASB Waterfront Theatre, until March 23. The set-up is simple: Deepan (Shaan Kesha) has discovered an old mixtape of his mother Sangeeta’s (Ambika GKR), from when she was a teenager in Sri Lanka at the start of the Sri Lankan civil war. An aspiring podcaster, Deepan convinces his mother to listen to the music with him; the staging then moves from Deepan and adult Sangeetha, on the right side of the stage, to musicians on the left, with scenes from Sangeetha’s childhood playing out with musical interludes. Each song is linked to a particular memory.

A Mixtape for Maladies, which is playing as part of the Auckland Arts Festival, is written by Ahilan Karunaharan, a Sri Lankan New Zealand playwright and actor. He performs the role of Rajan, Sangeetha’s father, in the show. According to the programme, this is the last of his “epic trilogy” of plays exploring Sri Lankan and New Zealand heritage, following TEA and The Mourning After.

While interwoven with the violent history of the Sri Lankan civil war, A Mixtape for Maladies only rarely touches on this directly. After all, even when trouble is brewing and your father keeps hosting political meetings in the back room, there are still crushes to be had, brothers to tease and fairs to attend. That this is a family who deeply love and care for each other is clear. I loved the recurrent scenes of Tiahli Martyn and Ravikanth Gurunathan, as Sangeeta’s sister Subbalaxmi and brother Vishwanathan respectively, looking at each other in exasperation as their sister ditches them to spend more time with Anton (Bala Murali Shingade), her secret boyfriend. At these moments, it really felt like I’d been invited into a village in northern Sri Lanka, one of the family. There for the cotton candy and bickering; there, too for frantic and frightening phone calls, sorrow seeping into the living room, into the old record player.

The first half of the show did start to feel formulaic; scene, song, commentary from Deepan and Sangeetha; scene, song, commentary. The set formula became more appealing when the actors started breaking it. There’s something electrifying in seeing Vishwanathan (Ravikanth Gurunathan) bound across the stage to sing a very angry version of La Bamba after a fight with his father. And perhaps the most poignant moment in the show is when the present day Sangeetha, having slipped into the past where she is saying goodbye to her sister for the last time, calls out “Pause, rewind,” replaying the embrace against scratchy sound effects.

As Sangeetha’s past and present selves mix on stage, Ambika’s acting strengths shine. That bewildered grieving, a past revealed that she doesn’t want to face again. I loved how the costuming played with these different versions of her self: teenage Sangeetha (Gemma-Jayde Naidoo) wears a vibrant sari, has her hair pulled back, while adult Sangeetha wears a casual, loose house dress, seems more unsure. I admired the range of emotion Ambika brought to her adult character, which went far beyond the simple tension of “I don’t want to tell you about my past because then I’d have to tell you everything” that she presents to her son.

Deepan, Sangeetha’s son (Shaan Kesha), is meant to be a sort of representative for the audience. He knows just the bare facts about the conflict that he can recite to prompt a reaction out of his mother (and educate the audience, as most people in New Zealand know very little about Sri Lanka’s decades-long civil war). Despite his ability to list musicians’ names (one of the weakest parts of the script) he has somehow never asked his mother to tell him more about how the war that killed at least 100,000 civilians affected her family. The best part of their relationship was a brief, joking argument over whether he should go to the temple more or get a better job, compared to another friend whose mother pays for his petrol. I wished that Kesha had been given more material to work with than simply being asked to react to things or state the obvious (ie. “but if that hadn’t happened you wouldn’t have moved to New Zealand and I wouldn’t be here”).

The play brushes against big topics. Why does Subbalaximi prefer to listen to music in Hindi and English, rather than Sinhala or Tamil? Why is “world music” a category that is so often its own silo, separated from popular music performed by English speakers? How do structures of religion like temples and churches unite communities, both in Sri Lanka and in the diaspora? What does it mean when those religious buildings are being bombed during conflict?

While I could glimpse these broad, interesting ideas within the script, the story mostly ends up focusing on closer to home stuff. “Everyone had a secret boyfriend back then” is a delightful provocation, especially when two characters actually do get secret boyfriends (played by the same actor, Shingade). I especially loved the dynamic between Gurunathan, as bouncy Vishwanathan, and Martyn and Naidoo as his sisters. Their family relationship is so strong that I felt like much of the more didactic aspects of the script, listing particular casualties in the war, musicians’ names or, for that matter, advice on making the perfect playlist could have been skipped entirely, to allow more nuanced interactions between different generations of a family.

Yet overall, some of these weaknesses in the script and staging can be ignored in favour of overall coherence and spectacle. The music is stunning, particularly Seyorn Arunagirnathan’s Carnatic violin. It’s so exciting to see a performance in Auckland where music is so integrated, especially music in a different language, and the actors do some incredible singing and dancing. Despite covering heavy subjects, A Mixtape for Maladies is often funny and tender, and left me wanting to wear more saris and learn more about the Sri Lankan civil war.