An Australian wētā lookalike was first noticed in Pukekohe in 1990. Now the stroppy biting insects are common from Auckland up to Cape Reinga.

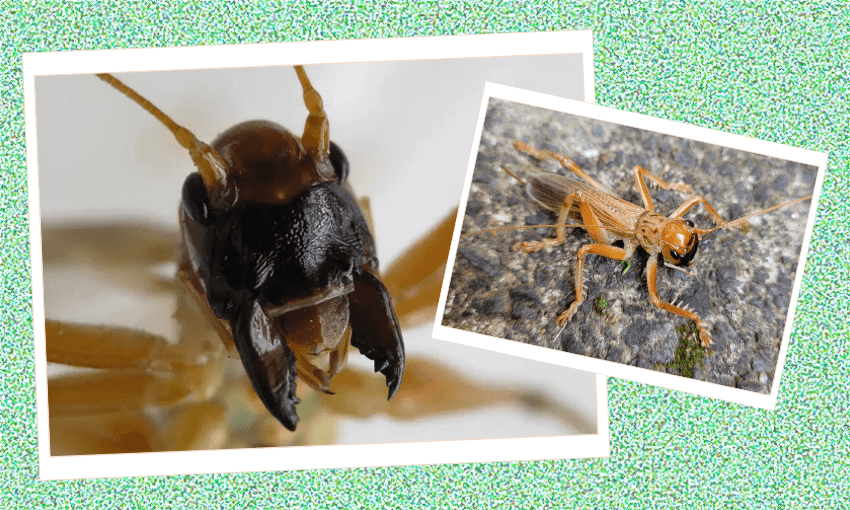

New enemies have been appearing in my house. They’ve got a big head, long spiky legs, a lumpy abdomen and antennae longer than their body – features that defined them in my head as wētā, a beloved and feared native icon. But when I tried to sweep the bug from my sink into a jar, it got angry. Really angry. This was not one of the gentle giants that Ruud Kleinpaste can’t resist placing on his face. This one was snapping its mouth-pincers and on its back were translucent laced wings.

“They have pretty fierce mandibles,” says John Early, Auckland Museum’s research associate of entomology. They’ve also got “quite a bit of attitude, and are quite stroppy”. He explains that though their looks have earned them the name winged wētā, these bugs are not wētā at all. They’re a species of pterapotrechus – crickets from Australia called raspy crickets, wood crickets or leaf-rolling crickets in their homeland.

Early can vouch that those mandibles are not just for show – in December 2008, when they were just starting to pop up in central Auckland, someone brought one into the museum, alive. Early kept it in a big container with a little pot plant “for a while” in his office. He kindly fed it with mealworm larvae, but one day “it bit me”. Now, that bug is a pinned specimen in Auckland Museum’s entomology collection, along with 20 other pterapotrechus and hundreds of thousands of other bugs.

In New Zealand, pterapotrechus were first discovered in a house in Pukekohe, South Auckland, in 1990. How it got there remains unknown, but Early thinks it was probably an “inadvertent hitchhiker” that slipped through biocontrol. “For years, they were only ever found sporadically, sort of within a couple of kilometers’ radius of Pukekohe Hill,” he says. Then one or two popped up in the Coromandel Peninsula in the late 1990s and after that they started appearing “out Waiuku ways” and around Auckland. Now, they’re “really common” throughout Auckland and all the way up to Cape Reinga. Just a few weeks ago Early found some “just hiding” under the creeper on his fence. “As I trimmed it, out they popped.”

Early attributes their gradual spread not so much to their wings but rather their sneaky behaviour. During the day, winged wētā hide in little nooks – shoes, drawers and even inside garden hoses. “I suspect they get shifted around as people shift house and move all their goods,” he says. He expects that soon they will be hitching rides south to Waikato and beyond.

Though they’re carnivorous, bitey and easily angered, whether they’re truly evil remains to be seen. For Early the “big questions” are the effects they could have on native species: are they going to be voracious predators and wipe things out? Will they outcompete our native wētās? Will they invade native forest habitats? “It’ll take ages before someone finally gets around to doing a study on it,” he says, because unless there’s already strong evidence bugs are a threat or problem, “there just won’t be any funding”.

He does offer up another set of bugs as a comparison. The whē, our native praying mantis, has “basically disappeared” from large areas. “I don’t think you’ll find it in urban Auckland any more,” he says. Since the 1970s, another mantis has appeared instead – the South African praying mantis. While the whē is always bright green and adults have purple dots on the inside of each foreleg, the South African praying mantis’ colours can range from brown to bright green and have no lovely dots. Also, our native female does not eat her mate, though a few native males have been lost to the appetites of South African females.

Non-entomologists have probably not noticed the difference, you have to look closely and know what to look for. A 2011 article in the Forest and Bird magazine says that the South African mantis has “proliferated pretty much unmolested” as a wolf in sheep’s clothing and taken over. Early says that the decline of the whē is possibly tied to other factors too, like the arrival of Asian paper wasps. Still, the South African mantis “certainly is out-competing our native one”.

So should I simply squash my new enemies in a bid to eradicate them instead of risking a bite trying to relocate them outside? Early doesn’t think so. “I don’t think there’s much point, really, because they’re truly here to stay.” I get the feeling unless it’s for scientific purposes, he would advocate no bug being squashed ever. The problem with bugs, he says, is that people “give them a pretty bad rap and just think that they ought to be squished”. Without them, he says we’d be “knee-deep in waste and stuff that didn’t break down.”

Early reckons the next time a winged wētā pays me a visit, I should keep it. Put it in a container, give it a little pot plant, and watch it. “They’re interesting creatures,” he says. It might lay eggs in the soil, or spin a shelter from silk, like his did in 2008. The bite, it seems, has been forgiven.