New research shows New Zealand is developing its own landed gentry, with almost half of homes now worth more than $1m, writes Justin Lester.

Those who purchased homes before 2005 have become middle class millionaires, while a social chasm has opened between home owners and their non-home owning peers.

The data science company Dot Loves Data, where I’m government director, used Homes.co.nz sales price estimates for 1.64m New Zealand homes to show that close to 800,000 houses are now worth more than $1m. My colleague, Dot Loves Data director Tamsyn Hilder, puts it like this: “The surge in housing values has turned many homeowners into millionaires, but on the flipside it has now pushed homeownership out of reach for many other Kiwis.”

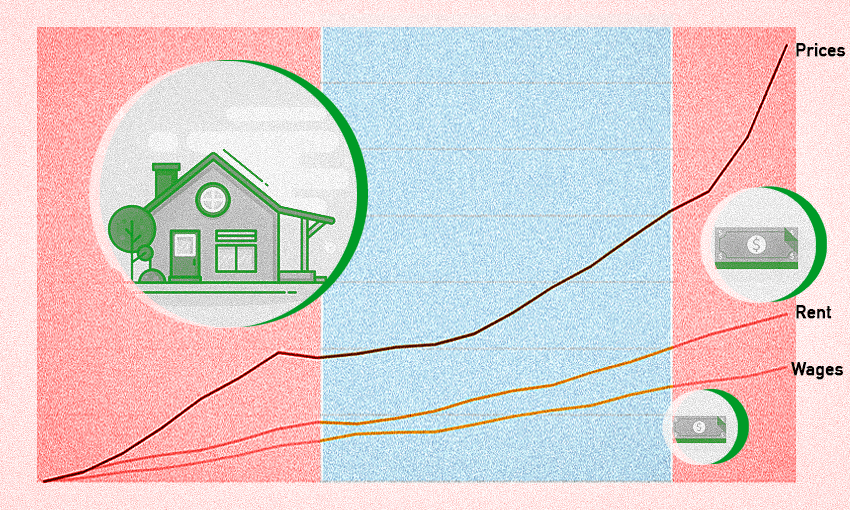

Incomes have increased, but not as fast as home prices. This means many people are stuck renting or have to move somewhere more affordable if they want to buy a home. “In one sense, we have a middle class made wealthy by rising property wealth,” says Tamsyn, “while renting families are struggling to afford the internet and basic household bills.”

To understand the rise of middle class homeowners, we analysed New Zealand house prices in May 2022 by regional location to determine what percentage of homes cost over $1m. We also considered this against increasing property wealth over the last 30 years.

Between 1992 and 2022 New Zealand house prices rose an average of 7.2% per year, outpacing other OECD countries and shooting New Zealand up the international leaderboard. A consequence, however, has been to turn long-term homeowners into millionaires and non-homeowning Kiwis into relative paupers, which has also widened the intergenerational wealth divide between old and young, and a social chasm between home owners and non-home owners.

In the United States, six million homes (8%) are valued at over $1m. In Australia, it’s 25%. In New Zealand, a stratospheric 45% cost more than $1m, and in the most exclusive regions, it’s even higher still.

Eighty-five percent of homes in the Queenstown Lakes district are worth more than a million dollars, the highest in the country. Auckland followed in second place at 76%, while Wellington was a close third at 75.6%. The common factors amongst these locations were high levels of educational attainment, high household income, low levels of unemployment and, consequently, very low levels of deprivation. Tauranga (61%) and Thames-Coromandel at (58%) closed out the top five, predominantly benefiting from the Auckland halo effect.

Auckland and Queenstown locations also featured strongly in the most expensive suburbs or communities. Ninety-eight percent of homes in Riverhead were valued at over $1m, the highest percentage of any suburban location, followed by Omaha, Waimauku and Arrowtown.

The least expensive areas were predominantly rural and South Island-based. Buller had the lowest number of millionaire homeowners at 1%. Its West Coast counterparts Greymouth and Westport were second on 1% and fourth on 1.7%, with Waimate wedged in between on 1.5%. The least expensive North Island district was Ruapehu, with 2.2% of homes costing over $1m.

While the ballooning prices have been beneficial for those owning one or more properties, New Zealand is at risk of becoming a country of property haves and have nots, with access to the bank of mum and dad becoming a prerequisite in order to climb onto the housing ladder.

Introducing New Zealand’s fastest growing bank

Parents are now New Zealand’s fastest growing home lender, according to a recent survey by Consumer NZ. The Bank of Mum and Dad has become the fifth largest lender in New Zealand and is catching up to banks ANZ, ASB, Westpac and BNZ. Fourteen percent of families have supported their children to buy a property, with the average contribution being $108,000.

According to Tamsyn, “Put simply, if you don’t inherit a home or funds from the Bank of Mum and Dad, you won’t own your own home, no matter how hard you work and save. We’ve calculated that the average Auckland earner would need to save for 17 years for a 20% home deposit, let alone paying off their mortgage. The social divide is already a chasm.”

The results are already becoming clear with young people living with their parents longer and delaying having children. While prices are currently declining, the average home price still remains more than eight times the average income, compared with a three times multiple in 1980, four times in 1990 and six times in 2008, at the beginning of the Global Financial Crisis.

Some solutions are evident in other countries. In Singapore 78% of residents live in state housing. Germany introduced a federal rent control in 2015. In Japan, a centralised and permissive regulatory system is focused on creating abundant housing, rather than parochial nimby obstructionism.

New Zealand is likely to need some or all of the above changes. If we don’t do something dramatic, home ownership will soon be a privilege reserved for the wealthy few – or those with access to the Bank of Mum and Dad.

Follow Bernard Hickey’s When the Facts Change on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.