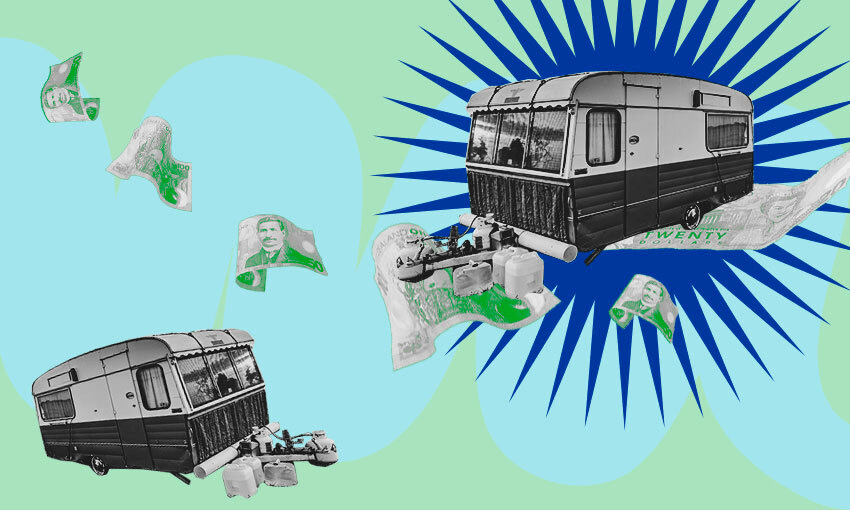

With the average price of a classic Kiwi caravan now over five figures, an unglamorous summer holiday tradition is increasingly out of reach.

I’ve been priced out of the caravan market. Just like my generation’s dreams of homeownership, the summer caravan holiday is now seemingly out of reach.

Across the country, every second backyard seems to have a 1970s caravan parked up, grass growing high around the hubcaps. On the outskirts of my hometown of Clyde, dozens of Oxfords, Anglos and Zephyrs fill a bare section, waiting for holidaymakers from Dunedin and Southland to reclaim them for summer.

So when my young family and I went on our first weekend away to camp at Lake Wanaka’s Glendhu Bay and we saw two iconic little ’70s caravans parked up by the lake, I began to wonder whether I too could be the proud owner of an Anglo Imp or Oxford Sprite. We began dreaming of ditching the tent and starting a family tradition: summer holidays parked by the sea or on a lakeshore, swimming all day and retreating inside when the weather inevitably turned to a southerly, where we’d listen as the rain drummed down on the aluminium roof.

The dream lasted as long as a Trade Me search. Old, reliable and ubiquitous, the caravans I was expecting to see would be about the same price as a 1996 Toyota Corolla. I was wrong. A rusty 10-foot 1973 Anglo Imp, with orange trim, pink and walnut-vinyl interior and a floral sofabed will set you back $12,000. A restored 1972 Oxford, complete with ’70s crockery and a lava lamp, is listed for $20,000. A restored 1971 Zephyr called ‘Blueberry’ is listed for $25,000. Even an unfinished Oxford restoration project is listed for $12,000.

Forget the housing market, New Zealand is in the middle of a caravan crisis.

Western Bay Caravans owner Erin McCoard says I’m a few years too late. McCoard has been restoring and selling caravans for 25 years, first in Hamilton and now in Katikati, and says retro caravans have gone from almost worthless to a prized asset in just over a decade.

“Fifteen years ago the old caravans weren’t worth a tin of shit,” he says. “We used to just strip the parts off that we wanted and then take them to the bloody demolition derby in Hamilton at the stock car track and we’d smash them up. People just about cry when you tell them that now, but no one wanted them.

“In the last two or three years it’s gone nuts. If I knew back then what was going to happen I would have bought every New Zealand caravan I could lay my hands on and I would be a multi-millionaire.”

He says the price has probably tripled in the last few years and even a $10,000 caravan will likely require thousands of dollars of work to fix leaks and restore.

“Anything under $10,000 you’ll have to work on.”

The reasons are an echo of the price inflation occurring throughout the country. McCoard says people are spending their overseas travel budgets on domestic travel and, while in an apparent abundance, there is also a limited supply of 1960s and 70s caravans.

“The old caravans, while some are buggered, the ones that are left are all that’s left, so once you get demand for them there’s only one thing that happens: the price goes up.”

He says a lot of the demand has come from baby boomers who are buying the kind of caravans they holidayed in growing up.

“They want to show their kids and grandkids what they did when they were kids.”

McCoard was raised in the business of caravan manufacturing. His father built them in Hamilton during the 1960s and 1970s, working for Anglo when the city was a hub for the industry and the country was churning out tens of thousands of orange and beige caravans.

“It was absolutely booming, they couldn’t make them fast enough. The factory was just down the road from where we lived. My job after school was to help them clean up and I saw how they built them. Unfortunately there aren’t a lot of guys with that knowledge that are left now.”

The industry came to a halt in 1978, when then prime minister Rob Muldoon introduced a 20% sales tax, seemingly targeted at summer pastimes – caravans, boats, ice cream and lawnmowers were among the goods picked out for a price hike. The local caravan industry was decimated.

“The whole industry collapsed and it never recovered,” McCoard says. “There were virtually no caravans built in New Zealand for 15 or 20 years. It’s a nightmare the way the whole industry’s gone.”

Caravans from England were soon imported, but McCoard says the NZ-made models have proved more durable, are cheaper to fix and remain far more popular.

“They used quality materials back then. They’re all glass and aluminium. They don’t rust, don’t rot, don’t deteriorate – they will last forever. The New Zealand caravans come up smiling every time.”

Caravan and Motorhome World owner Dave McRobbie has been selling and restoring caravans in Hamilton for over 45 years – some of the retro caravans he sells would have been new, made locally, when he started out. He says prices have more than doubled since Covid and he’s having difficulty getting secondhand stock.

“Now they want exorbitant prices for things that need doing up,” McRobbie says. “A few years ago we were picking them up for between $2000 and $5000 and now they want between $10,000 and $15,000. It’s just due to the level of interest in them. People are wanting to go back to the old New Zealand-made ones.”

But McRobbie says there are still deals to be found. He says he recently bought four caravans for less than $500.

“They are few and far between now. By the time I’d put them on a truck and got them here it cost about $1000 each, but that’s all they’re worth because they need $10,000 to $15,000 of work on them.”

McRobbie says New Zealand would have been building about 30,000 caravans a year in the 1970s boom, before Muldoon’s sales tax.

“Since then, you’d be lucky if there’s been 10,000 built.”

Even renting a caravan is in hot demand. Clinton Wells has been selling and renting out caravans in Rotorua for almost 40 years and has a fleet of 218 older caravans rented at $140–$160 a week for a minimum term of three months.

“In the last 18 months the rental side of the business has just blown up,” Wells says. “We just can’t get enough stock now and at the moment we’ve only got five in the sales yard, but we’re not even getting them listed and they’ve sold.”

However, he said the rental market isn’t holidaymakers, but people at a loose end who are living in them.

“Unfortunately a lot of people are having to sell their homes, or they’re renovating or building – we’ve had a few house fires – and people are living in caravans while they rebuild or renovate.”

He says that while imported caravans go down in price, the more reliable Kiwi caravans – like your TrailLite, Liteweight, Oxford or Classic – tend to go up in price. Like housing, people could actually view them as an investment.

“You could buy an Oxford for $15,000 and in 10 years’ time it’s probably worth $22,000, whereas the English caravans you might pay $25,000 for now but you might be lucky to get $16,000 in a decade’s time.”

While it’s dispiriting for young families having their camping dreams dashed on the rocks of rampant inflation and a pandemic-fueled spend-up, McCoard says for those who have been through the highs and lows of NZ’s caravan industry, it’s been a boon.

“Covid has done a lot of businesses harm, but on the opposite side of the coin guys like myself are having a booming time. It’s our time to shine in the sun.”