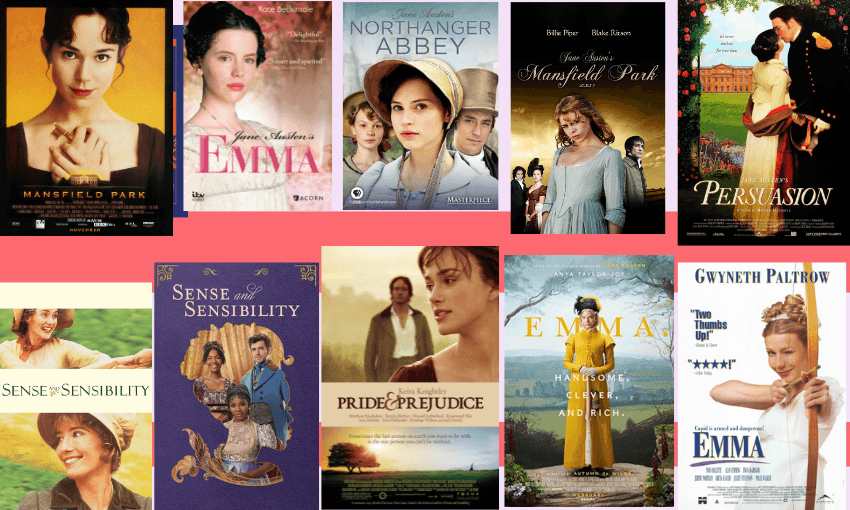

Books editor Claire Mabey appraises all the Austen-adapted films from 1990 onwards to separate the delightful from the duds.

For the purists, read our ranking of Jane Austen’s novels here.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that not everything is created equal. Since 1990 there have been 12 attempts to translate Jane Austen into the medium of film with mixed results indeed. Below you will find travesties and treasures alike.

To keep things clean I’ve stuck to straight adaptations and left out the inspired-bys like Clueless, Bridget Jones, Lost in Austen and The Lizzie Bennet Diaries.

The quality that set the top three films apart from the rest was close and intelligent attention to the source material across all layers of production: from screenplay to casting, costume to cinematography, and surprisingly (to this viewer), the score. Music really does do so much work to elevate emotion, conjure tone, and complement the interpersonal tensions and intensities that Austen was so exceptional at orchestrating on the page. The best films capture the tone of the books: whether that is mischief, heartbreak, anxiety or the absurdity and necessity of youth and romance.

Dear reader, I warn you now that I am unapologetically harsh on the films that failed to recognise that audiences are supremely capable of being endlessly diverted by Austen’s own script. There is no need to Yassify her heroines. No cause to break fourth walls, or spike the dialogue with neologisms, or mash Georgian costumes with contemporary couture. If you’re going to translate Austen then do it faithfully or not at all. Which does not mean you cannot be inventive and modern. It simply means one must not fuck it up.

Also, before you get het up, please note that the BBC Pride & Prejudice adaptation isn’t included because it’s a TV show. I’ve done my best to push the spectre of its excellence from my mind as I binged the films but its example is always with us. As you’ll soon see, the mid-90s spawned a cluster of Austen adaptations and the Beeb’s Firth-filled feast remains one of the era’s great cultural totems. Its longevity also begs a debate on whether Austen is best suited for the serialisation of TV or the swallow-me-whole potential of film.

Herewith are all 12 film adaptations (from 1990 onwards) ranked from worst to best.

12. Persuasion, 2022 (directed by Carrie Cracknell)

This attempt is an affront to Austen, an affront to Anne Elliot and frankly, an affront to film making. Dakota Johnson, lovely and brilliant as she is, is wasted in this crude attempt to force Persuasion (truly, the greatest of the novels for many fans, though not this one) into the 21st Century.

In this version Anne Elliot breaks the fourth wall continuously with David Brent-like asides to camera; quips, glances and smirks. The script departs wildly from Austen with lines like this: “He listens with his whole body. It’s electrifying.” And: “Now we’re strangers. Worse than strangers. We’re exes.” Anne Elliot would never utter such dross. Nor would she mooch around with black and white rabbit in her lap as if she is about to whip out a magician’s wand and top hat and stuff it in there. Anne was a busy woman: the calm amid a storm of familial upheaval. She did not have time for mooching or for rabbits.

Cosmo Jarvis’s Captain Wentworth is wooden and uninteresting with Ariana Grande eyebrows that failed to elicit any twinge of empathy from this viewer. Mia McKenna-Bruce’s Mary Musgrove is fatally miscast: she is not merely depressed and self-centered (as she ought to be) but whining and huffy to the point of unbearable.

Even reliable old Richard E Grant couldn’t rescue this chaos. Between his melodramatic turns, and the forced giggling of the Musgrove sisters, this is a hollow attempt to make Austen relevant to a younger audience.

I’m sorry to be so harsh. But I beg of you, do not put yourself through this. If you’re a fan of Austen’s most graceful heroine, this movie will greatly displease you.

11. Mansfield Park, 2007 (directed by Iain B. MacDonald)

Just to briefly recap what this book is actually about, Austen novel-ranker, Hannah August, summarises: “Fanny Price is the eldest daughter of a mother who made an ill-advised marriage and is struggling with a bothersome number of offspring. Fortunately Fanny’s aunts, who made better matrimonial and procreational choices, decide that they can take Fanny under their wing, and she moves to live with her four cousins at the country estate of Mansfield Park.”

Billie Piper plays Fanny Price in this made-for-TV film and one wants to wish her well in the endeavour. Unfortunately, the attempt is lacking. Fanny Price is a tricky heroine: she is a fish out of water and in this state must be the slippery heart of the whole show. Piper tries but the whole production lacks tension. I lost interest halfway through and didn’t care to stay til the end.

10. Sense and Sensibility, 2024 (directed by Roger M. Bobb)

This made-for-TV film for the Hallmark Channel is, while surprisingly watchable, a tad thin. Taking its cue from Bridgerton, there are some contemporary elements: black actors play the lead roles, Kiss from a Rose by Seal is performed by the string quartet at one of the balls, and the costumes veer towards magenta.

Unfortunately it’s all a little too Hallmark: designed to be picked up in haste and offered lightly. It’s not at all bad, but a reminder that you do tend to get what you pay for.

9. Persuasion, 2007 (directed by Adrian Shergold)

This attempt at least remains faithful to the tone of Persuasion. But Sally Hawkins just doesn’t do as Anne Elliot. Hawkins is tentative, timid and blushing: she doesn’t offer the inner strength and great capacity that Anne Elliot ought to possess.

Nevertheless, it is a faithful enough attempt and many aspects are pleasing: it’s well paced, suitably gloomily lit, and Julia Davis plays Elizabeth Elliot (Anne’s sister): a small role but a treat for Davis fans.

8. Emma, 1996 (directed by Diarmuid Lawrence)

I have a soft spot for Kate Beckinsale. She has one of the best Instagram accounts out there (dressed-up posh cats, and mad/sky-high platform boots/charming pranks on her elderly mother). And in this early point in her career she is an excellent Emma: wily, over confident and charming. Well-timed cutaways are used to reveal Emma’s inner fantasies – the kind we’re all capable of having when we’re sure our good (if not wildly misdirected) deeds will result in adoration and thanks.

The surrounding cast is mostly banging, too: Samantha Morton plays Harriet Smith and she is distraught when she must be, daft when required, and innocent when needed.

Mark Strong, however, is miscast as Mr Knightley. He has far too villainous a countenance to be an acceptable Knightley. He leans too far into the severe and the scolding; and his thinning hair is an all-too realistic reminder of how much older he is than the object of his affections. Knightley and Emma’s eventual kiss is a real cold fish: a chilly anticlimax.

7. Pride and Prejudice, 2005 (directed by Joe Wright)

The spectre of the BBC P & P (Colin Firth / Jennifer Ehle) hangs heavy over this one. As it will over the just-announced forthcoming film starring Emma Corrin as Elizabeth Bennet, Olivia Coleman as Mrs Bennet, and Jack Lowden as Mr Darcy (very promising casting; one must, one supposes, endeavour to reserve judgment over the fact that it’s Dolly Alderton who has written the screenplay).

This cinema-release adaptation was flashy news back in the day. Keira Knightley was a star of the age and high hopes were pinned. And the film did live up to some of them. There is a pleasing chemistry between Knightley’s Elizabeth Bennet and Rosamund Pike’s Jane Bennet (the relationship between the two eldest sisters is a lynchpin); and Matthew Macfadyen is a tolerable Darcy. However Donald Sutherland is an eerie Mr Bennet. Teeth so white, manner so… repressed. In the novel Mr Bennet is spiteful and pithy; here he is angsty and … so Donald Sutherland.

I appreciate the attention to locations in this film: there is an appropriate contrast between the farmy, chicken-ridden yard of the Bennet home versus the grandeur of Darcy’s stony mansion. The all-important fields (striding through long grass is essential in any Austen adaptation) have a starring role, especially in that magnificent (if not a touch melodramatic) dawn scene in which Lizzie and Darcy get close enough to pash.

However I’m irked by Jena Malone’s Lydia Bennet. It’s not fair to compare her to Julia Sawalha (BBC) but one does. And Malone’s attempt is not a patch.

While the film is … fine, it’s safe to say that some of the stars went on to do greater things (Knightley, Black Doves; Macfadyen, Succession; Malone, Hunger Games; Mulligan, too many to list).

6. Northanger Abbey, 2007 (directed by Jon Jones)

Now, this one surprised me. It’s a very silly book and this is a perfectly silly film. Felicity Jones is a superb Catherine Morland: youthful, earnest and she conveys the giddy attraction to the gothic and all the fright and lust and fear of sexuality that it offers an unmarried woman desperate for someone to ask her father for her hand in marriage.

This production does an excellent job of evoking the times: when Catherine is taken to Bath there are scenes in teeming ballrooms, bodies crushing in more ways than one. The streets are plagued by carriages, and attention is paid to the stark differences between Catherine’s loving, cosy home and the vast, cold Abbey that is haunted by cruelty.

And Carey Mulligan! Fresh from her turn as a Bennet sister (Kitty, in the 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice) she is scene-stealing as the manipulative Isabella who toys with the affections of Catherine’s brother.

5. Mansfield Park, 1999 (directed by Patricia Rozema)

We’re really starting to cook with gas in this decade-ending cinematic release. I have always liked this film: it’s haunting in the way that the novel is haunting (although critics have accused it of changing the moral tone of the novel by posing a heavy critique of slavery whereas the novel is more ambiguous). Mansfield Park is an unsettled place: Fanny Price is pulled out of her class and rehomed in one built upon the lives of others. And that uneasy tone infects the entire story.

Lindsay Duncan plays both Lady Bertram (Fanny Price’s wealthy Aunt) and Mrs Price (Fanny’s mum): the mother figures on either end of the socioeconomic spectrum that Fanny is trapped between. As Lady Bertram Duncan is a laudanum soaked fop, cuddling her pug and blithely opting out of the worries and troubles of both family and society. As Mrs Price she is the harried, weathered mother of too many children and wife to a very unpleasant man. “I married for love,” she says, very pointedly, to Fanny who is wrestling with her own romantic choices.

Frances O’Connor is the best Fanny Price. She is anxious without being irritating, subservient without being meek, and good-humoured without all the giggling. One can really get behind her and Edmund’s (played empathetically by Jonny Lee Miller) love story if one can forget that they are in fact cousins.

Patricia Rozema’s plot tweaks and weaving of Fanny Price’s character with Austen’s own is smart: the result is a beautifully constructed and paced film that has impact, grace, wit and depth.

4. Emma, 1996 (directed by Douglas McGrath)

While this 90s banger didn’t make it to the podium it did land in a respectable fourth position thanks to excellent casting and, once again, attention to tone.

Gwyneth Paltrow is a delightful and elegant Emma. She’s wily, open-hearted and sweet. A nifty employment of voiceover lets us into Emma’s sneakier, more judgemental side; the costumes are perfect (light, pastel, fairytale-like which suits a story in which the love interest is Knightley and the home is Hartfield); and the soundtrack is exceptionally good. A plinky, mischievous tune accompanies Emma’s extraction of Harriet Smith’s confidences and winds itself around all the juiciest, gossipiest scenes.

The rest of the cast is spot on, too: a stroke of genius putting Alan Cumming in the role of Mr Elton who is absurd and entertaining. Toni Collette is a perfect Harriet Smith: all blushes and frowns and dimples. Ewan McGregor an ideal Frank Churchill: detestable. Jeremy Northam is a handsome and not-too-severe Mr Knightley. And Juliet Stephenson is one of the best Mrs Elton’s (severely unlikeable – talks while eating and breathes loudly through her nose – but comically so).

But the star of this show is Sophie Thompson’s Miss Bates. Fluttery, nervous, determinedly optimistic Miss Bates. In Thompson’s hands she is doe-eyed and lamb-like and dithery and vulnerable: the perfect foil for Emma’s impatience and her vanity in that vicious yet crucial picnic scene.

3. Persuasion, 1995 (directed by Roger Michell)

This is one of the first grown up movies I remember seeing at the cinema. I got hissed at for rustling my packet of salt and vinegar chippies and I had confused thoughts about why a man would have to put his hand right up a bum of a lady he was boosting up onto one of those horse-drawn carts they’re forever clopping around in. I couldn’t see why all the ladies around me were swooning over Ciarán Hinds’ Captain Wentworth. To me, as a 10-year-old, he was old and a bit scary-looking.

Thirty-odd years later and the clouds have parted. This is the best adaptation of Persuasion yet, and a film that pays deep respect to the source material and the time and place in which it was created.

What I love about this film is that it takes time to survey all that lies between the central interactions and dramas of the lead characters: shots of cart wheels turning, sheep flocking, tenant farmers, servants, food and fields. Key locations of Bath and Lyme Regis are fully appreciated, as are interiors of homes. Some shots are like oil paintings: the figures positioned in the dim light so sumptuously you feel transported.

Sophie Thompson (Miss Bates in the 1996 Emma) is, once again, superb as Mary Musgrove: sickly, anxious, self-centred. She is immensely watchable, even as her character is hard work. Mary contrasts perfectly with long-suffering, sad Anne Elliot played to utter perfection by Amanda Root.

Root makes Anne the line between her narcissistic family and the world that keeps them afloat (the servants, the workers, the land and the sea). She is tired and tireless. Root conveys Anne’s regrets, as well as Anne’s resolve, in every scene. What many fans love about the novel is that Anne is an unlikely hero: she’s a background character in her own life, a spinster at the whim of her family’s needs and wants. The film pays enormous respect to her position – always showing Anne in relation to others – so when past mistakes are forgiven and love rekindled the drama is intense and understated at the same time. Exquisite!

2. Emma, 2020 (directed by Autumn de Wilde)

Really quite brilliant. Eleanor Catton wrote the screenplay for this film and boy did she maintain her golden, post-Booker Prize rep with this one. De Wilde and Catton understood the assignment: every scene works to convey character, conflict and tone which makes for an enchanting viewer experience.

“Men of sense do not want silly wives,” says Mr Knightley (played lushly and passionately by maverick musician and actor Johnny Flynn) early on. This film makes clear the central project of Emma: Mr Knightley is in love with someone who has not reached her potential and he must try to school her into getting there so he can finally pop the question. “Better to have no sense at all than to misapply it as you do,” he says to Emma. Burn! It’s a great premise for conflict: flighty, clueless (see what I did there) love interest is watched over by impatient elder who is only just managing to keep it in his jodhpurs.

Anya Taylor-Joy’s Emma is fantastically stubborn, confident and ruinously bored. From the very start we learn that Emma is spoiled (she’s first seen directing a servant to cut the flowers she wants from her lovely hot house), and heartbroken (the flowers are for her governess Miss Taylor (Gemma Whelan) who is leaving her to get married). She is a young woman about to be left alone with her hypochondriac father (Bill Nighy – who is always himself and here, it works) and in need of company and projects to occupy her.

This film focuses itself on Emma’s character development and all else spools from there. Taylor-Joy starts off spiky and aloof, and by the end she’s all eyes awash with tears and a blood nose from stress and surprise. Her unravelling is superbly paced which makes the romance between her and Knightley eminently believable and joyous once all the messes are happily resolved.

The rest of the cast is a constellation of stars: Josh O’Connor is an unhinged Mr Elton, loopy and sinister by turns. Miranda Hart is an immensely sympathetic Miss Bates, almost as good as Sophie Thompson’s (item four, above). Connor Swindells is an endearingly wan Mr Martin (the farmer in love with poor Harriet Smith who is grossly misled by Emma into aiming for someone “better”), and Amber Andersen is the best Jane Fairfax yet (Jane is the highly accomplished niece of Miss Bates who Emma is horribly jealous of).

What really makes this film fly is attention to costume, location and music. Costumes are cunningly designed to mirror sets: when we first see Emma she’s in a yellow as bright as the blooms behind her. When she’s wrestling with her mistakes in an outdoor scene with Knightley the pattern of her dress and her jewellery mirrors the foliage and flowers of the tree behind them.

The haberdashery is a recurring location which is a genius motif: so much information passes between characters in the perusal of fabric. It is where members of different classes mix and meet; where gossip is overheard.

The music too (taking full advantage of Flynn’s talent as a folk musician) reflects class and values: there are hymns sung by church choirs, and folk tunes sung in a workers tradition – fewer voices, every word is heard. All of the elements of the production work to accentuate the nature of the village of Highbury and how Knightley and Emma are the posh pair at the heart of it.

An altogether handsome and clever production that I’d happily watch over and over again.

1. Sense and Sensibility, 1995 (directed by Ang Lee)

I have lost count of the number of times I’ve watched this masterpiece. The combination of Ang Lee’s sensitive direction and Emma Thompson’s screenplay (of which she spent five years perfecting) is pure magic.

This film has everything you ever need from Austen. The baddest baddie (Greg Wise has never recovered in my estimations: to me he’ll always be Willoughby the blaggard), the most beautiful and hopeless romantic (Kate Winslet is heaven as Marianne Dashwood), the best and most burdened big sister (Emma Thompson’s Elinor Dashwood), the innocence of youth (delightful Margaret Dashwood played by Emilie Francois), anxious mother (Gemma Jones), brooding heartbroken handsome military man (Alan Rickman’s bass-toned Colonel Brandon) and dithery happily ever after (Hugh Grant’s stuttering Edward Ferrars). And that’s not even mentioning Harriet Walter as Fanny Dashwood: a foreshadowing of the brilliance she’d later turn out in Succession.

Lee’s direction is majestic. There are long, sweeping shots of the marshlands that the Dashwood women are downgraded to (into their cottage with the fire that smokes); wide shots of glittering and oppressive balls; dim, mist-covered fields that Marianne attaches her romantic visions to.

Once again I have to bang on about tone. Lee and Thompson achieve a resonance, a gravity in this story that the novel actually struggles to achieve. The scene in which a feverish Marianne lies sweating and mumbling in a four-poster is devastating. Winslet and Thompson fully reveal how essential the sister relationship is. How lonely the world is without women to share your plight and your pressure. Particularly when all your hopes depend on men.

Yet there is also comedy. The gravity of serious and sad is shaken up with moments of such well-placed comedy that emerges from the sillier characters: Imelda Staunton as Mrs Palmer and Hugh Laurie as her long-suffering husband. Elizabeth Spriggs as Mrs Jenkins and Robert Hardy as Sir John Middleton snatch every scene they’re in; and Imogen Stubb’s Lucy Steele is teeth-grindingly ick.

Lee’s Sense & Sensibility revels in the manners of the period. The bowing and the politeness and the decorum. This film reveals just how much of life was conducted through law, and rules and expectations. This is one of those instances where I could confidently declare that the film is better than the book.

So there we have it. The definitive ranking. No further correspondence shall be entered into unless you put fountain pen to paper, seal it with wax and send it by carrier on horseback.

Rather just read the books? Here’s our ranking of Jane Austen’s novels.