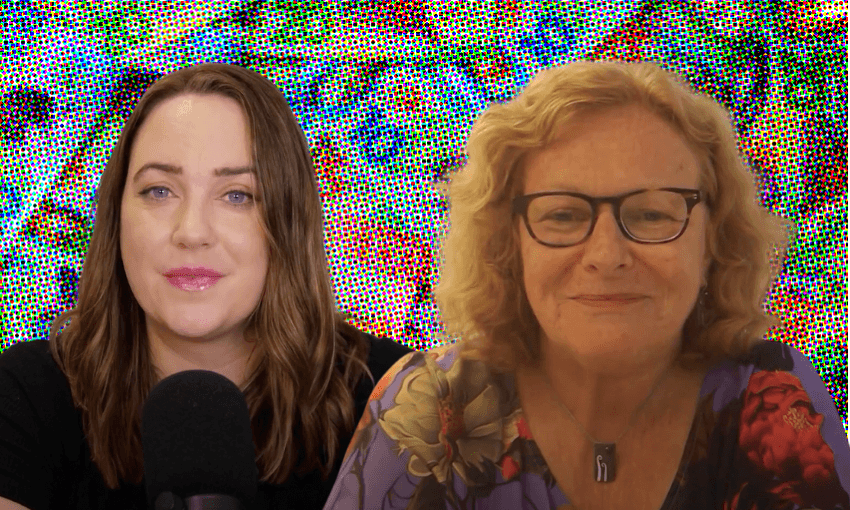

Retirement commissioner Jane Wrightson talks to Frances Cook about her money regrets, and the changes she’d like to see for New Zealanders.

Even people whose job it is to think about money all day can have money regrets. For retirement commissioner Jane Wrightson, she knows exactly what hers is: she didn’t take enough risks with her money when she was younger, and had the time to let those calculated risks pay off.

On the Making Cents podcast, she says it probably means she has less money today than she could have otherwise.

“I think my risk tolerance was too conservative,” Wrightson admits. “I was always saying I’m a balanced person, so I’ll just sit in balanced. But when you’re younger, that’s completely nut bar when you’re thinking about long-term growth.”

It’s the kind of financial hindsight that a lot of people can relate to, especially women. Financial studies are everywhere, showing that fewer women invest, yet when they do, they’re better at it than the men.

But Wrightson had her reasons for being more conservative. That caution around money partly stemmed from her upbringing: her parents grew up during the Great Depression, and left school at 12 and 14 because there was no money.

“All of that sort of sits as a real backdrop to you from your own family background. While I’ve been very fortunate by comparison, like most boomers, the caution around that, the still living knowledge of poverty is interesting, right? I don’t think it leaves you. Even if you’re comparatively well off, you always think it could all disappear tomorrow.”

Wrightson’s job now is to look to the future.

The commission is working to prepare the next generation of New Zealanders for retirement, ideally with fewer regrets and more resilience.

That means pushing for better education, changes to KiwiSaver, and even rethinking how we build our homes.

KiwiSaver changes? She’d make a few

Wrightson is a fan of KiwiSaver. “It’s a bloody good scheme,” she says. “We’re lucky to have it.”

But she also sees room for improvement. Her top wishlist item? Move default contributions to 4% from both employees and employers. “Three percent isn’t enough,” she says. “But because that’s the minimum, a lot of people assume it must be the right number.”

Wrightson has been quietly talking to employers about whether there could be appetite to make minimum contributions 4%, with an employer match. That would mean the average person saving at least 8% of their salary, which could make all the difference in retirement.

She says employers have been more receptive to the idea than she’d feared. “Most of the employers so far have been more positive than I would have thought to be honest. They kind of said you just give us a bit of a runway and we think we can do that,” she says.

“Those people who have worked in the States or in UK will know that their employment contributions are big. And so three to four percent here, I don’t think is outrageously awful, actually.”

Look over the ditch, and Australians are saving 12% of their salary, and also get generous tax breaks to encourage them to save as much as possible.

But that’s where Wrightson draws the line. “I think, don’t forget, they don’t have NZ Super in the way that we do, right? So that’s kind of the difference. And the tax breaks that are available in Australia cost a huge amount of money. So when people say we can’t afford NZ Super, for instance, and we know we need to be more like Australia, higher private savings, we go, look at the cost of private savings.”

Other wishlist items? Getting rid of total remuneration packaging, where employers include their KiwiSaver contribution as part of your salary, rather than on top. “It’s not how it was intended to work, and it cheats people out of thousands over time.”

Then there’s the self-employed. Unlike employees, they don’t get employer contributions, and many opt out entirely. Wrightson says she wants to explore whether targeted incentives could help, especially for sole traders. “It won’t be for everyone, but we need to look at it. There are big equity gaps.”

Teach money younger, make it normal

There’s endless debate in the money world about how much inequality comes down to personal responsibility, versus structural problems. Wrightson says it’s always a mix, but she believes part of the solution is education. The type of education that’s available to everyone, from a young age.

It used to be a larger part of schooling, but seems to have disappeared in recent decades. Wrightson wants to bring it back, and she doesn’t just mean telling teenagers to budget. She wants a full financial education framework in schools, starting from Year 1.

“Right from the beginning, it’s things like where money comes from, what it’s for,” she says. “By the later years, it’s investing, budgeting, debt. We’ve got pilots running now with Inland Revenue teaching kids what tax is, and they’re loving it. It can be fun.”

The goal is to build financial thinking into everyday life, the same way brushing your teeth or tying your shoes becomes second nature. “Money isn’t everything, but it touches everything,” Wrightson says. “If you don’t understand it, your life goals will be harder to reach.”

Housing, retirement, and realism

Another issue Wrightson keeps flagging: housing. A lack of affordable housing means there’s a looming crisis of people renting through their retirement, instead of having the paid-off home our pension system was designed for.

We’re also building houses that don’t fit the country’s needs. “We keep building townhouses with stairs, or massive family homes,” she says. “But what about the couple or the single person who wants a one-bedroom, single-level, low-maintenance home close to services?”

This lack of housing variety means it’s both harder for first home buyers to find an affordable home, and for older people to downsize and cash in the equity they’ve built up in the house.

It’s not an area where Wrightson directly has as much power, but she still wants to be the squeaky wheel, pointing out how much it’s harming everyone’s financial life.

Save yourself from the biggest money mistakes

There’s an old saying in politics that if you affect one big change in your career, you can consider it successful. Wrightson knows she’s got her work cut out to address the laundry list of issues she’d like to tackle.

So what would she tell her younger self? Or anyone just getting started? “Get your emergency fund sorted. Stay in KiwiSaver. Try to contribute 4% or more if you can.” Otherwise, a life curveball can throw you into crisis.

“If your car breaks down or you lose your job, and you don’t have that savings buffer, that’s when people try to raid their KiwiSaver or fall into really bad debt.”

It’s those simple wins that can prove the most powerful over time. They’re also the ones that as individuals, we have more power to take control over.

Meanwhile, Wrightson will keep pushing behind the scenes for those bigger housing and KiwiSaver changes that could be the game changer.