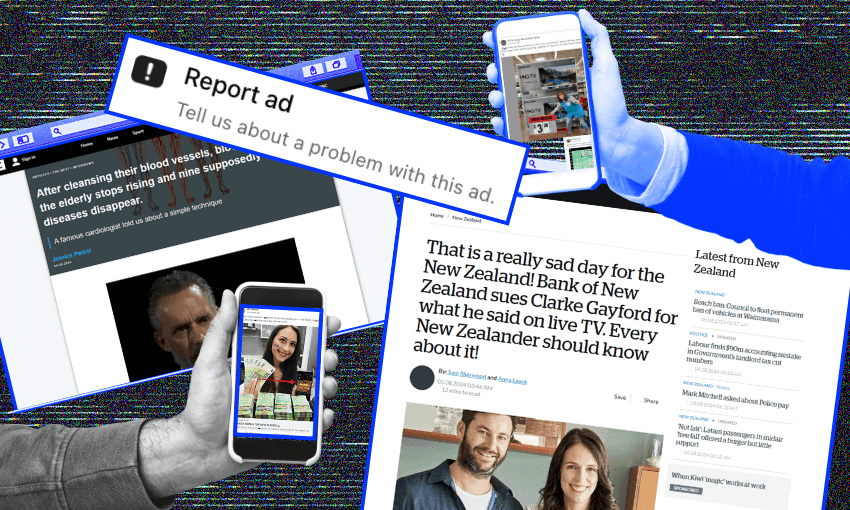

From dubious health claims to too-good-to-be-true deals to bizarre clickbait confessions from famous people, scam ads are filling Facebook feeds, sucking users in and ripping them off. So why won’t Meta do anything about it?

I’ve had a Facebook account since 2006, when it first became available to the general public. Like many, I’ve found the experience on Facebook to be increasingly alienating and unappealing – filled with AI garbage and showing me far more content from pages I’ve never engaged with than from people I’m friends with. As such I tend to check the site only once or twice every few days.

But another thing has been showing itself to me every time I visit my Facebook feed lately – scam ads.

You know the ones, a photo of a celebrity and some clickbait headline claim. Clarke Gayford was a popular option for a while.

There are also the ones with a fake business page that are offering some amazing savings on last year’s technology, or an overstocked warehouse. For a while it was a plethora of fake Pak’n’Save pages.

The specifics of the scam vary – some are trying to convince users to join an online investment scam, others claim to be selling a product that is likely to be nothing more than a way to steal credit card details – but one thing is consistent: they are using entirely false claims as well as illicitly leveraging identities and brands to exploit the users who view them.

Last year New Zealand consumers lost nearly $200 million to online scams and, while there’s no information to break down the pathways by which these victims were targeted, at least some were likely taken in by Facebook ads placed by scammers. Surely if they weren’t successful, the scammers wouldn’t keep using them.

Facebook’s terms are clear on many of these matters. “Ads must not promote products, services, schemes or offers using identified deceptive or misleading practices, including those meant to scam people out of money or personal information.”

But, of course, Facebook has a process for this. You can report these scam ads, which clearly violate Facebook’s advertising standards including those things advertisers “must not” do and many more.

And, in most cases, you file a report and then… radio silence. Sometimes if you’re lucky you’ll get a notification some days later saying there’s a response. If you click through, you land in your “support inbox”, where there will be an answer to your report.

And in the vast majority of cases, for me anyway, that answer is essentially “nup, all good here”.

I have made dozens of reports, and the majority of them seem to end up resolved like this. A lot of them have the same coincidental timing too, with the reply coming exactly six days and 12 hours, to the minute, after I filed my report.

The reply above is to my report of this ad.

Needless to say, Harvey Norman wasn’t really selling TVs for $3 each. The post was clearly in breach of a number of Facebook’s advertising standards, but exactly six days and 12 hours after I reported it, Facebook decided to take no action.

In practice, however, even if they had taken action, it was probably too late. The pages running these ads are often created just hours before they start running the ads, and the ad campaigns only operate for a few days before they move on to a new page and a new hook for future victims.

A similar page, Laptops Elimination, was created on July 18 and was running its ads the same day. Now, a few weeks later, the page remains but the operators have seemingly moved on, leaving it dormant and no longer running its scam ads.

I reported the ads I saw from that page too, of course, but again no action was taken. And my report about the page itself, as operating a scam, has remained unanswered.

Similarly, my report about the very fake Rockshop page, which I specified was impersonating a real business (including a link to the real Rockshop Facebook page) was met with a familiar reply exactly six days and 12 hours after my initial report. It was even a little more explicit about the process than the responses to the ad reports had been – “we’ve taken a look and found that the page doesn’t go against our Community Standards”.

This page was created on July 19 (NZT) as “18 07 2024” before being renamed to “Rockshop NZ”. It went from 0 followers and likes to 2,300 of each in a few days. This page made 10 posts to its timeline in eight minutes and posted nothing else until it started running an ad a few days later.

This page does not go against Facebook’s community standards, which Facebook uses to review all reports. It doesn’t go against the one that prohibits impersonation and inauthentic content posting. And it doesn’t go against the ones about fraud and deception.

All this reporting, and screenshotting, and recording of details is, of course, time consuming. Even tracking down the outcome of a lot of these reports requires effort and some level of technical skill.

And the reporting system itself is frustrating and difficult to engage with. The main “support inbox” is poorly organised and difficult to navigate (especially if, like me, you’ve been reporting a lot of things). Most ad reports end up in the “other” section, but within that there’s no easy way to see the status of any report, or how many updates there are. The reports themselves contain no reference to what was reported.

And a surprising number of reports seem to end up in some sort of limbo, with an unannounced response that your report failed. I have no idea how you’d figure out what you’d actually reported or find it again to resubmit the report.

But it’s not all bad news! Facebook does actually provide some form of transparency about the ads it runs through its ad library.

If you visit the Facebook page of the advertiser, and then click About, and then click Page Transparency, and then click See All, and then click Go to Ad Library… then you can (usually) see what ads the page is currently running and was running in the past (I say “usually” because sometimes, even when you’ve just followed links from an ad you were shown on the timeline, you will be told there are no ads running).

And within this ad library, sometimes there are some very interesting things to see.

In most cases there’s little more than the ad you’ve just been shown as the page was set up only to pump one specific scam for a few days. But, in other cases the operator is running dozens of ads targeting territories all over the world, each with different bait.

This advertiser has run hundreds of ads, the majority of which are now showing (amazingly) that they’ve been removed for breaching Facebook’s terms of service.

For some reason, an account that has had countless ads removed, and was even disabled at some point, is still active again and allowed to run new ads. The most recent are clearly targeting users in South Africa and Finland.

When I first encountered this specific page it was running a campaign that is probably familiar to many New Zealand Facebook users.

As well as using localised clickbait to attract attention, the ad was also passing itself off as being from a local news outlet.

The URL hint in the link suggests the content is from nzherald.co.nz and a user who clicks the ad will land on a page that is designed to look like the Herald.

Some go even further, using AI tools to create videos purporting to be endorsements by celebrities or politicians. I’ve seen prime minister Christopher Luxon, deputy prime minister Winston Peters, minister of health Shane Reti as well as celebrities Peter Jackson and Russell Crowe.

Online gambling

The explicit scams are only part of the problem. Another very prolific category of advertising on Facebook is online gambling.

Ads for these online gaming sites promise real-money returns and suggest real-money buy-in from players. Of course, Facebook is quite specific about how online gambling can be advertised.

Meta defines online gambling and games as any product or service where anything of monetary value is included as part of a method of entry and prize. “Ads that promote online gambling and gaming are only allowed with our prior written permission,” according to the Meta Business Help Centre. “Authorised advertisers must follow all applicable laws and include targeting criteria consistent with Meta’s targeting requirements.”

So in this case, I guess Mandy Daniels1 – a page with three likes and five followers, and five total posts – is an authorised advertiser? As is MY Waitlist – a page with no likes, followers or posts, that was created the day before it started running very convincing ads about Maru from Auckland who bought her dream car with euros.

It’s honestly a little hard to know exactly what these ads are promoting because following them leads to a gamified onboarding process that I was somewhat reluctant to put myself through. But they certainly make themselves out to be a product where something of “monetary value is included as part of a method of entry and prize”.

Health claims

Beyond explicit scams and gambling products there also exists a massive market for dubious health products making dramatic claims in very misleading ways that would clearly contravene New Zealand law.

These products use the same tactics as the financial scams, exploiting the likeness of high-profile people and brands, and linking to websites that replicate the look and feel of legitimate news organisations.

One ad I’ve seen frequently from a number of different pages uses an AI-generated interview with Sir Peter Jackson to make extreme claims about a miracle medicine that will cure high blood pressure. This medicine is, naturally, being suppressed by the mainstream.

Facebook users living with hypertension who might want to know what magic cure Sir Peter has found will be directed to a page designed to look like a BBC news article which, bafflingly, claims Jordan Peterson is a cardiologist.

If they scroll far enough through the thousands of words in the fake article, explaining how Professor Peterson has found a way to cleanse blood vessels, and past a written testimonial from Sir Peter Jackson, they will find the miracle product.

It’s hemp gummies. The miracle cure for Peter Jackson’s cardiovascular disease was hemp gummies.

Of course, Meta does have a specific policy on the advertising of CBD products… It requires prior written permission, which I’m sure Sunny Hillside received:

“Ads that promote or offer the sale of cannabidiol (CBD) or similar cannabinoid products are only allowed with prior written permission. Meta requires advertisers promoting CBD products to be certified with LegitScript. Certified advertisers must comply with all applicable local laws, required or established industry codes and guidelines, including Meta’s targeting requirements.”

Despite Meta’s policies around advertising medicines, which require adherence to relevant local laws, these ads are also prolific. And they, like all the other scam ads, are frequently posted by clearly inauthentic accounts with no meaningful engagement on the site.

In one case, an ad for a diabetes remedy was marked by Facebook as disinformation, but was continuing to run.

Meta’s complicity

At some point, I think, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that Facebook’s inaction on this is a choice.

It stretches credibility to suggest that a company that has invested tens of billions of dollars in artificial intelligence lacks the capability to seriously impede the use of their advertising products to target users.

According to Meta’s official guidelines for advertisers, all ads are reviewed before they go live to users. “Our ad review process starts automatically before ads begin running, and is typically completed within 24 hours, although it may take longer in some cases,” is how Meta describes its process.

This means that before any of these scam ads could have appeared on my, or your, timeline, they have been proactively approved by Meta. These are the ads that Meta has deemed acceptable to show to users.

Of course, Meta is also clear that it uses automated processes as part of its approval process. But those automated processes are designed and implemented by Meta.

Weaknesses in those processes have been exploited for years by scammers and seemingly go unaddressed – they can create a new page and run scam ads in minutes; they can trick Facebook’s systems into lying about the domain names ads will redirect to; they can reuse copy and images from ads that were previously removed; they can copy posts and images from the legitimate and verified business accounts they are imitating.

And, after all of that, the manual reporting systems that are meant to act as a backstop, and which should allow users to protect themselves and others from these scams, are barely functional and seemingly not fit for purpose.

This is not the first time I’ve tried to write about these issues. In the past I’ve given up because it was too difficult to get Meta to engage.

The typical response from Facebook’s external PR agency when I’ve provided examples of scam ads is a request for specific information about those ads. This is then followed by a response along the lines of “we’ve escalated it and will take action if necessary” – meaning specifically that those ads, or the pages running them, will probably get taken down manually.

This is not about a few specific ads. It’s not about any of the more than 100 scam ads I’ve screenshotted since thinking about writing this. It’s about the choices Meta is making that allow them to exist in the first place.

But I have tried again to engage with Meta for this story, and this time I reached out directly to Australia/NZ head of corporate communications, Joanna Stevens. I provided a number of examples of the ads, the responses I’d received to my reports and a list of questions about Facebook’s overall handling of this issue.

Joanna responded quickly – just a few hours later.

I’m sorry to hear about your experience. I’ve forwarded your email to our escalations team so they can investigate the issues you have raised.

In the meantime, could I trouble you to send links to any of the advertisers/ads you mention (in addition to the screen shots you’ve shared)?

No response to any question, or even the suggestion that a response might be coming. Just a request for the specifics so they could, no doubt, deal with the ones I mentioned and call it a job well done.

I could have ended it there and said “I reached out to Meta about these issues, however they opted not to provide responses to my questions,” but I actually want answers on this, and more than that I’d like to see some real change.

So I provided a detailed follow-up with multiple further examples, including a number of ads I was served in the time it took to write my response, including one featuring an AI-manipulated video of prime minister Christopher Luxon promoting an investment scam.

And I repeated my questions.

After a three-hour response time to my first email, eight business days have passed since my follow-up and I’ve received no response at all. Although the specific reports I highlighted in that second email did get resolved soon after, all of them deemed to be in violation of Meta’s terms.

However, the pages running those ads, including the fake Rockshop, still appear to be intact, perhaps able to run ads again in the future.

What to do?

At some point, it seems, Meta’s apparent inability to mitigate these threats to New Zealand consumers should be of interest to local regulators and legislators. The company profits massively from New Zealanders, but at the same time is serving them up on a platter to scammers and doing the bare minimum to protect them.

It’s unclear which regulatory agency in New Zealand might take the lead on something like this, but in response to emailed questions Sally Whineray Groom, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment’s acting manager of consumer policy, said, “The government takes the issue of scams and fraud seriously. There are a number of initiatives happening across government designed to reduce incidents of scams on individuals and entities through education and raising awareness, investigating alleged scams and prosecuting cases of fraud.”

The statement also pointed out the broad scope of the challenge, mentioning that aspects of enforcement and investigation are undertaken by the NZ Police, CERT NZ, the Serious Fraud Office, Department of Internal Affairs, the Financial Markets Authority, the Commerce Commission and the Reserve Bank.

So there are clearly plenty of agencies with an interest in the issues, but can any actually do anything? And are any looking at Meta’s role in facilitating access to victims (for a fee)?

And ultimately, does Facebook even have a legal liability in this matter? It’s unclear, as is the question of whether New Zealand authorities could meaningfully require specific action from Meta.

However, a US court has recently ruled that Australian billionaire Andrew Forrest can proceed in his lawsuit against Meta for negligence in allowing scam advertisers to use his image in their ads on the platform. If they can, potentially, be negligent in allowing the use of Forrest’s image, could they also be negligent in allowing scammers to target users?

Even if that were a legal standard that was established, most scam victims (and potential victims) don’t have the resources of a mining magnate to take on one of the world’s richest tech companies.

Ultimately, Meta should be expected to do better in protecting users from exploitation, and it should be compelled to do so by the agencies charged with protecting the interests of New Zealand consumers

It is time for the New Zealand government (and, frankly, regulators around the world) to demand more of Meta, and do all they can to hold them accountable for the harm caused by their choices and their inaction.

First published August 21, 2024.