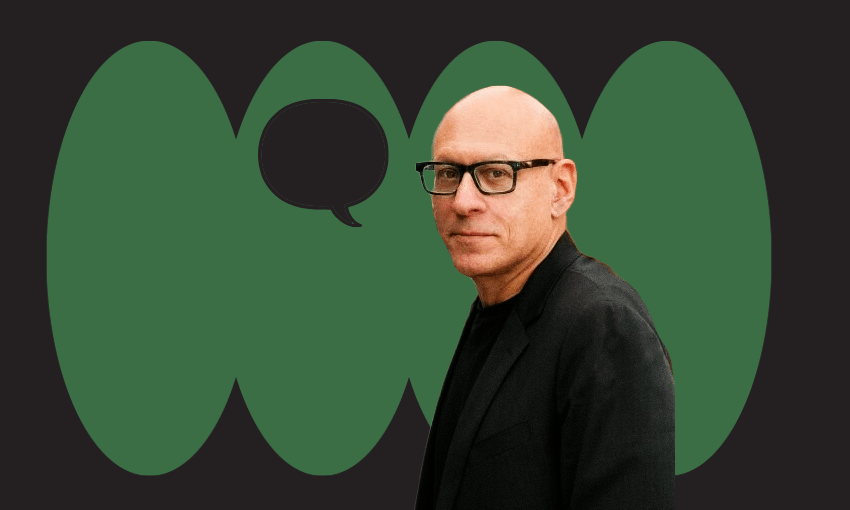

David Shields started out as a novelist before ditching that format to create collage-like books and films. In anticipation of his Auckland workshop next weekend, Megan Dunn asked him about his finely honed craft.

I can’t remember when I fell out of love with the novel. Probably about the same time I realised I couldn’t write one.

The American author David Shields is best known for his landmark book-length collage, Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, first published in 2010. The book is composed mainly of quotes from other authors, arranged into numbered vignettes and presented in 26 chapters, one for each letter of the alphabet.

Shields started out as a novelist but wanted to convey a more urgent sense of how life is lived now. “I recognise in myself both the hunger for the irreducibly real, and also the impossibility of totally getting there,” he says.

Reality Hunger argues that fiction and non-fiction are distinctions that are flimsy at best. For me – someone who still secretly dreams of writing a novel, but is no longer able to read one – it’s a comfort read, a sign that I’m not alone in a pothole, having lost the plot (although of course I am alone in a pothole, having lost the plot).

Shields is the author of over 20 books. This year, he published The Very Last Interview. It’s a Q&A, without the A. Throughout his 40-year writing career, Shields has been asked, according to his estimation, over 2,000 questions. He removed his replies, then rewrote and remixed the questions to produce this passive-aggressive page-turner. “What’s the worst thing a reviewer can do?” “Have you ever imagined killing a critic?” I laughed, but only because I felt caught out. Nude.

Shields’ favourite paintings are Rembrandt’s late self-portraits, for “their unbelievable nakedness”. “He just seems like this very mortal, very vulnerable, very naked man. And I think it’s that impulse that I recognize in the art that I love the most.”

The moment I saw his cut and paste (workshop) pop up in this year’s Auckland Writers Festival, I booked my place.

ON COLLAGE

Megan: In the workshop you’ll discuss the art of collage, using Dinty Moore’s Son of Mr. Green Jeans.

Moore’s essay is arranged alphabetically and contains a list of real and fictional fathers, from Tim Allen in Home Improvement to the actress Laura Chapin, who played a daughter in the 1950s sitcom Father Knows Best, but whose own father abused her.

Why this essay?

David: It’s funny because just today Tony Dow died; he played Wally in Leave it to Beaver, another American television show. And Dinty’s piece also mentions Leave it to Beaver.

I’d argue that book-length collage is a complex form that is harder to write well than a conventional novel.

To me, collage has a mathematical exactitude. It’s not just, “Oh gee, let’s throw together hundreds of pages that are vaguely about somebody’s life.” For collage to work, it has to be very, very precisely calibrated, and Dinty’s essay is very, very carefully calibrated.

Son of Mr. Green Jeans is only about 1,500 words long and it has five different strata: animals who take care of their young; parents who mistreat their human young; pop culture and the TV shows Dinty watched as a child; Dinty growing up with an alcoholic father; in the “present”, Dinty and his wife deciding whether to have a child.

And rather miraculously, these strata all come together. It’s a very sophisticated work, in a very small space.

If you don’t know what collage is, I can say, well here it is, in microcosm.

ON REALITY HUNGER

Megan: Did you have any idea that your own collage book Reality Hunger would make the impact that it did?

David: I really didn’t. Twelve years later, I still get emails almost daily, or certainly weekly, from people who say some version of “I thought I was crazy for not liking the conventional novel. I’m interested in something that’s more diaristic or epigrammatic and collage-like. Your book gave me the permission to explore what it is I’m interested in.’”

Megan: I was impressed by the seamlessness of Reality Hunger. How did the book come about?

David: I taught a graduate seminar over many years and would bring in hundreds of quotations. And every year I would cull and curate and rewrite and remix and organise these quotes. And then after about five or six years of this, I looked up one day and realized I had a book staring me in the face.

And then for a variety of reasons, Reality Hunger caught a little controversy because it was misunderstood to be “against copyright” and “against the novel”. I don’t think that’s what the book is. I’d written three novels and back then I was trying to write and read and teach conventional, realistic, linear fiction. And I was bored out of my mind. Reality Hunger is a book in favour of something that’s exciting.

ON MARSHAWN LYNCH: A HISTORY

Megan: Now you’ve also moved into film. Tell me about that editing process.

David: Lynch: A History is a documentary I made almost entirely made from a remix of found footage. It’s about American football but really, it’s about the former NFL player Marshawn Lynch, and his refusal to speak to the American media and how that’s a powerful mode and model of protest and a subtle deconstruction. Lynch embodies Camus’s dictum: “The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.”

My books and films are utterly adjacent: they’re collagistic, there’s a lot of found footage, a resistance to linear narrative, there’s a mixture of the personal and the cultural and the anthropological and, I hope, the “philosophical.”

Megan: Memes and GIFS seem like 21st century evolutions of the collage form. I looked up some of the Marshawn Lynch memes. Many use his oblique one-liner to the media: “You know why I’m here.”

David: I think that’s a beautiful point. Memes and GIFs are in a way the 21st century, equivalent of aphorisms because a one- or two-second or three-second clip of somebody shrugging in a certain way, or somebody expressing disdain or joy, might convey some sort of universal “meaning.”

A meme is the pictorial equivalent of an aphorism.

The Lynch film is 84 minutes long and composed from around 770 clips. Every clip is its own little GIF, perhaps.

ON POST MODERNISM WITH A HUMAN FACE

Megan: In a recent conversation with author Laura Kipnis, you said, “I’m interested only in postmodernism that has a distinctly human face.”

David: I’m not interested in trickery for trickery’s sake. I really love Simon Gray’s The Smoking Diaries. At one point, his typewriter key sticks, and there is no “H” for half a page. On some level, it’s sort of postmodern trickery. But by the end, he is almost literally narrating the book from his own deathbed and it’s extraordinarily self-conscious and you could argue hyper-postmodern. It’s also a deeply human and very nervy, candid, honest, heartbreaking book.

After he died, I wrote something in honour of Gray and his widow contacted me and said that Rembrandt’s late self-portraits were also Simon’s favourite artworks.

ON THE VERY LAST INTERVIEW

Megan: One of your book’s epigraphs is Gertrude Stein’s quote, “Remarks are not literature.” Yet your work is a strange refutation of that quote.

David: I agree. I’ve ordered this book in such a way that the questions are statements. Every chapter is prefaced by an epigraph. I personally love statements. I love aphorisms. I love the articulations of things. I love epigrammatic writing.

Megan: Same. The Richard Diebenkorn cover [see middle book cover, above] is a nice portrait of transference.

David: The whole book is about transference. The interviewer is endlessly asking questions and then the interviewee, some version of me, is not answering any of the questions.

The book (and the short film based on it) is a memento mori of a writer of a certain age confronting his own limitations as a person, a writer and as a mortal, and asking those middle-of-the-night questions. The whole point of the book is that I hope the reader asks similar questions of themselves.

Megan: And it is a speed read. There’s no fat on the sentences.

David: Right. It’s very minimal. I really wanted this feeling of hammered metal to it. Each sentence is a gunshot: boom, boom, boom, boom. It’s a brutal self-interrogation. So it was crucial that the questions come fast and furious.

David Shields: Cut and Paste workshop, Saturday 27th August, 11-12.30pm, Auckland Writers Festival