Staff at Kokomo said the artworks came from a specific website. The site’s owners deny it. So where did the portraits come from – and what are the cultural consequences of displaying them?

Nestled on a side street near Christchurch’s central city is Kokomo, a restaurant with industrial flair and earthy charm. Inside, a small forest of plants, natural timber, and pendant lampshades create a space designed for slow mornings and long brunches. Above the tables – where patrons sip oat milk flat whites or bite into scallop katsu sandos – hang three portraits of old Māori figures, long passed on.

The prints – portraying Ena Te Papatahi (Ngāpuhi), Te Wharekauri Tahuna (Ngāti Manawa) and Te Aho-o-te-Rangi Wharepu (Ngāti Mahuta) – are a focal point for people sitting in their vicinity. The figures will be familiar to anyone even slightly acquainted with historical New Zealand art. Mataora and moko kauae adorn the faces of the old Māori figures, wrapped in blankets on a marae ātea or smoking their tobacco pipe.

But the portraits, famously by Charles Frederick Goldie, are not originals. Not even close. They’re large, altered reproductions.

Ask the restaurant where they came from and they’ll say Art Motif. But there’s no seller by that name. Reach out to Pop Motif, with similar offerings, and they’ll say it wasn’t them. “We’ve never sold those,” a representative said. “It’s not us.” They suggested another possibility – New Zealand Fine Prints – but that company also denies any link, noting that while they do sell Goldie reproductions, these particular ones aren’t theirs.

So, where did the reproductions come from? Why are they hanging in a restaurant? And who, if anyone, is responsible?

‘They’re not artworks. They’re reproductions.’

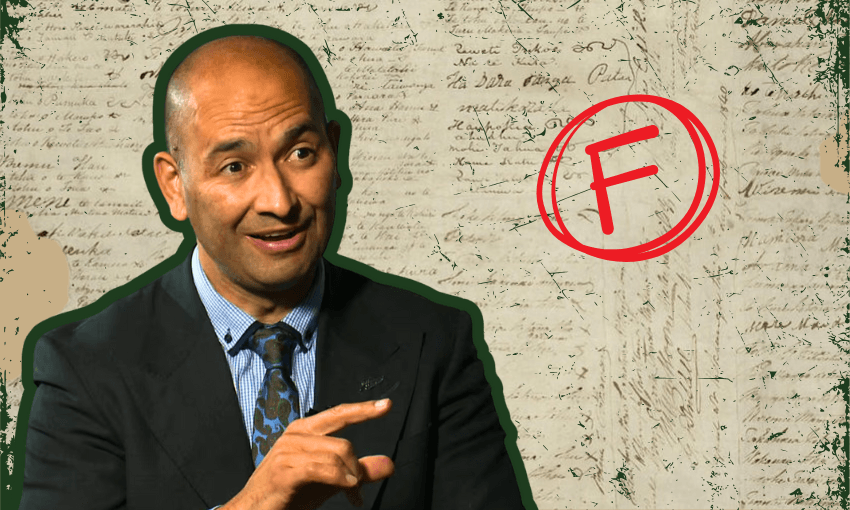

At Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, senior curator Māori, Nathan Pōhio, and curator of historical New Zealand art, Jane Davidson-Ladd, couldn’t be clearer: these images are not original works, nor are they creative acts. “They’re reproductions,” Pōhio says, “and we need to be precise about that language.” In other words: taking a portrait, applying a high-contrast filter, and printing it does not make it art.

However, the subject matter carries serious weight. Goldie’s portraits – many of them depicting Māori elders from iwi such as Ngāti Mahuta and Ngāti Maniapoto – are complex historical taonga. While Goldie was once dismissed by art historians for romanticising Māori as a “dying race”, his works have since been reassessed, partly because of renewed Māori engagement with them. Today, descendants of those depicted often regard the portraits with deep admiration.

That admiration is reflected in how the Auckland Art Gallery handles them. “We follow tikanga Māori,” Pōhio explains. “That means no food or drink near the portraits, karakia before exhibitions, and consultation with descendants before reproduction or display.”

The restaurant setting, then, is clearly at odds with this approach. “They’re in a space where food is consumed – that breaches tapu,” Davidson-Ladd says. “And I doubt there was any discussion with whānau before putting them up.”

Reproducing tūpuna without consent

At the heart of the issue is whakapapa. These are not anonymous subjects, but tūpuna with living descendants. Davidson-Ladd notes that even the gallery won’t put a portrait online without checking with the whānau. “Portraits carry mana,” she says. “And in te ao Māori, the image still holds the essence of the person.”

The law, however, doesn’t see it that way. Because Goldie died in 1947, his work entered the public domain in 1997. That means anyone can reproduce it – legally. Ethically, it’s another story.

“The law has never protected the sitter,” says Pohio. “It protects the artist. But tikanga Māori should guide us – and that means asking: What is your whakapapa to these people? Why are you reproducing them?”

There’s another twist in this tale. The images in Kokomo appear to have been passed through some kind of digital filter – perhaps AI, perhaps not – but the telltale signs of artificial intelligence are there: unnatural contrast, distortions in moko, a synthetic sheen.

Walter Langelaar, chair of the Aotearoa Digital Artists Network, describes the reproductions as “low quality and culturally hollow”. If AI was involved, he says, it likely scraped public-domain Goldie images and applied a filter or enhancement. “Anyone with an internet connection and a printer could’ve done it,” he says. “But the results – they flatten nuance, erase identity, and distort taonga.”

This isn’t new. Goldie has been forged before, most famously by Karl Sim in the 1980s, who changed his name to C.F. Goldie and sold homages under that signature. But with AI, the stakes feel different. “AI is not inherently unethical,” says Langelaar. “But it needs context. It needs intent. And it needs consent – especially when it’s depicting Māori ancestors.”

So why did the Kokomo owners want to display these pieces? Pōhio suggests there may be a deeper irony at play. “Ōtautahi has seen a cultural shift since the earthquakes. You see more Māori language, more Māori art, more presence.” It’s possible, he suggests, that Kokomo’s owners intended the portraits as a gesture of allyship or solidarity.

“But intent doesn’t equal impact,” Pōhio says. “And if you want to engage with Māori culture, there’s a process. It starts with relationships. Not reproduction.”

The restaurant did not respond to detailed questions in time for publication. But the silence itself speaks volumes. As Davidson-Ladd puts it: “This is an opportunity to educate – not to shame, but to inform. That’s how we move forward as Treaty partners.”

What do we owe our tūpuna and each other?

The ethics of representation extend far beyond one restaurant in Christchurch. As AI advances and reproductions proliferate, the ability to alter and commercialise images of tūpuna is no longer restricted to galleries or collectors – it’s in the hands of everyone.

That, says Pōhio, is the real danger. “It looks like a kite in the sky – pretty, but it means nothing. It’s disconnected from people, from context, from whakapapa.”

Instead, he and Davidson-Ladd urge artists, businesses, and the public to ask: Why am I doing this? Who does it serve? And who am I accountable to?

Because in the end, the answer isn’t about copyright. It’s about culture. And as Davidson-Ladd reminds us, “tikanga Māori is not optional. It’s how we show respect. It’s how we show we belong here.”

This is Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.