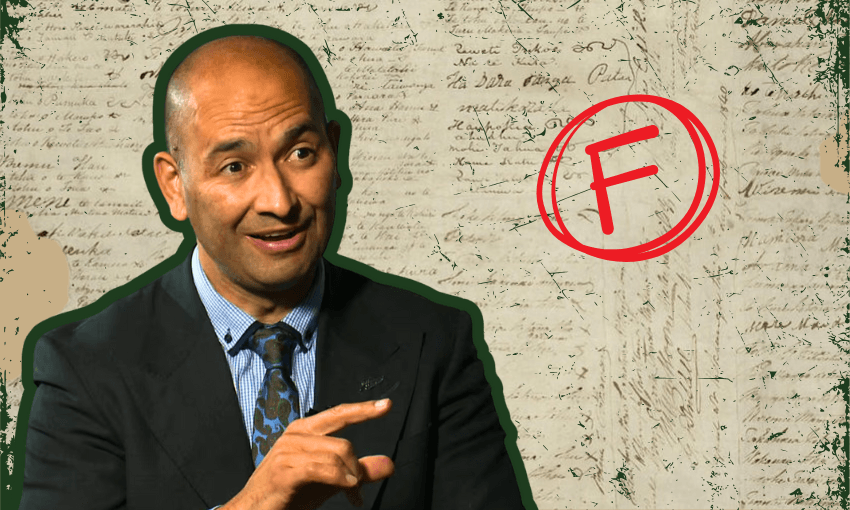

A new report from the auditor general reveals serious failings in how public agencies are honouring treaty settlement commitments and outlines what needs to change.

When iwi and hapū sign Treaty of Waitangi settlements with the Crown, they’re not just accepting redress for historic breaches. They’re entering into a renewed, long-term relationship with the state – one built on acknowledgment, apology and partnership. Already fragile and with a fraught history, those relationships are constantly under strain.

A new report from the controller and auditor general makes it clear that public organisations are not meeting the commitments laid out in treaty settlements. Despite a system that now spans more than 12,000 active obligations across roughly 150 public agencies, the Crown is underperforming and putting the durability of settlements at risk.

What are Treaty settlement commitments and why do they matter?

Since 1989, the Crown has been settling historic treaty breaches through legally binding deeds and legislation. These settlements include financial redress, cultural recognition, and mechanisms like co-governance or rights of first refusal on surplus Crown land. At the time of reporting, the Crown had paid $2.7 billion in financial and commercial redress, amounting to less than 3% of the estimated value of what was taken from Māori.

However, perhaps the most important part of each settlement is the promise of a new relationship between the Crown and Māori. One based not on grievance, but on partnership.

Public organisations like government departments, Crown entities, local authorities and state-owned enterprises are responsible for upholding these commitments. Unfortunately, says today’s report, they’re failing to do so consistently.

Treaty settlements impose a wide range of legally binding obligations on public organisations – from transferring Crown land and offering iwi rights of first refusal, to restoring traditional place names, making financial redress, and establishing relationship agreements or co-governance arrangements over rivers, mountains and conservation land. Agencies are also often required to consult iwi on planning or regulatory matters and to maintain ongoing engagement through formal protocols. While these obligations are clearly set out in settlement documents, the report found many public organisations either misunderstand them, fail to prioritise them, or lack the systems to track and fulfil them consistently.

Why was the report launched and what did it look at?

In response to concerns raised in 2022 that public agencies were struggling to meet Treaty settlement commitments – potentially undermining the settlements themselves – Cabinet approved the He Korowai Whakamana framework to improve oversight and accountability. Initially led by Te Arawhiti, the framework’s implementation and related responsibilities were transferred to Te Puni Kōkiri in February 2025. The auditor-general’s report, based on evidence gathered throughout 2024, aimed to assess whether current public sector arrangements are fit for purpose and whether agencies understand the legal, contractual and reputational risks involved.

What did the report find?

The team assessed how well the public sector is honouring settlement obligations. It reviewed both core Crown agencies (like ministries) and non-core agencies (like councils and Crown entities), as well as the wider system for monitoring progress.

The findings were scathing – widespread confusion, weak accountability, and a lack of systems to monitor or escalate risks. Despite nearly four decades of settlements, many agencies still treat them as one-off tasks, not as the beginning of long-term relationships with iwi and hapū.

Key problems the report identified include:

- A transactional mindset

Many agencies view settlements as checklists to be completed, not living commitments. Some didn’t even know what obligations they held or had conflicting records.

- No holistic framework

There’s no overarching strategy guiding agencies to coordinate with each other or manage overlapping responsibilities. This leads to duplication, delays and confusion.

- Inconsistent delivery

Some commitments are delayed by years, while others aren’t implemented at all. Gaps and breakdowns erode trust – and in some cases, have already triggered legal action.

- Lack of monitoring and reporting

Most agencies don’t track progress on their settlement obligations in a meaningful way. That means ministers, parliament and the public have little visibility over what’s working and what’s not.

- Inadequate support and guidance

Non-core agencies, which hold about 20% of all obligations, are especially under-supported. While core agencies have access to guidance under He Korowai Whakamana – a framework to improve how core Crown agencies monitor, report on, and uphold their Treaty settlement commitments – others are left to figure it out on their own.

- Te Haeata isn’t cutting it

The central online portal meant to track progress has major limitations. It doesn’t capture the full picture, and treats all updates as equal, regardless of scale or impact.

- Significant risks

The government has already paid tens of millions in compensation for failing to meet its obligations. However, the real cost is harder to quantify as it includes lost opportunities, damaged relationships and the threat of new grievances.

What’s changing and who’s responsible now?

Until recently, the agency responsible for overseeing post-settlement implementation was Te Arawhiti, the Office for Māori Crown Relations. But that’s now shifting. Earlier this year, those responsibilities were handed to Te Puni Kōkiri, the Ministry of Māori Development – which is fast becoming the “aunty with all the jobs”.

Already responsible for areas as wide-ranging as housing, whānau ora, te reo Māori, employment and Māori enterprise, Te Puni Kōkiri is now tasked with overseeing how public agencies fulfil their settlement commitments, managing post-settlement relationships, advising the Crown on Māori rights and interests, and leading on Takutai Moana matters.

Announced by minister for Māori affairs Tama Potaka in August last year, the changes are part of a broader government strategy to double the Māori economy by 2035. But they’ve also drawn criticism.

Labour leader Chris Hipkins warned the restructure could repeat the Crown’s past mistakes, while the Public Service Association – which represents 200 staff at Te Arawhiti – called the changes demoralising and poorly communicated. “It sends a signal that the agency will be left doing the bare minimum,” said PSA Kaihautū Māori Janice Panaho.

Others, like Leith Comer (former Te Puni Kōkiri chief executive), cautiously welcomed the move, saying the real test would be in how it’s implemented. That implementation now falls to Te Puni Kōkiri, under chief executive Dave Samuels – whose ministry is already under pressure, with mixed results across key indicators like Māori housing and economic development.

What does the report recommend?

To restore credibility and ensure settlements are honoured, the report calls for a major system reset:

- Develop a holistic framework

Te Puni Kōkiri should lead a cross-agency approach to settlement delivery that reflects the full, long-term intent of these agreements.

- Improve planning and risk management

All public agencies should review how they plan for and monitor settlement responsibilities – including how they identify risks and escalate them.

- Strengthen expectations on leadership

Ministers, boards and the Public Service Commission need to ensure Treaty obligations are built into performance expectations for chief executives and governance bodies.

- Fix the right of first refusal process

Land Information New Zealand must urgently improve how it handles the right of first refusal process for land titles and give better support to agencies. These rights grant a long-term option for iwi to purchase or lease Crown-owned land and are essential tools for iwi to build their economic base.

- Upgrade Te Haeata and annual reporting

Agencies need to report more clearly and publicly on their progress. Transparency matters, especially to iwi waiting for answers.

- Extend He Korowai Whakamana

This oversight framework should apply to all agencies with settlement duties – not just those in the core public service.

- Regularly assess the system

Te Puni Kōkiri should report annually to the Māori Affairs Select Committee on how well the public sector is honouring its promises.

What’s the bottom line?

The auditor general’s report reads as a clear warning that if public organisations continue to treat settlements as paperwork, they risk undoing decades of progress.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.