Teenage memories so often populate one place. For Sharon Lam, it was the original bus exchange on the corner of Colombo and Lichfield Street.

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

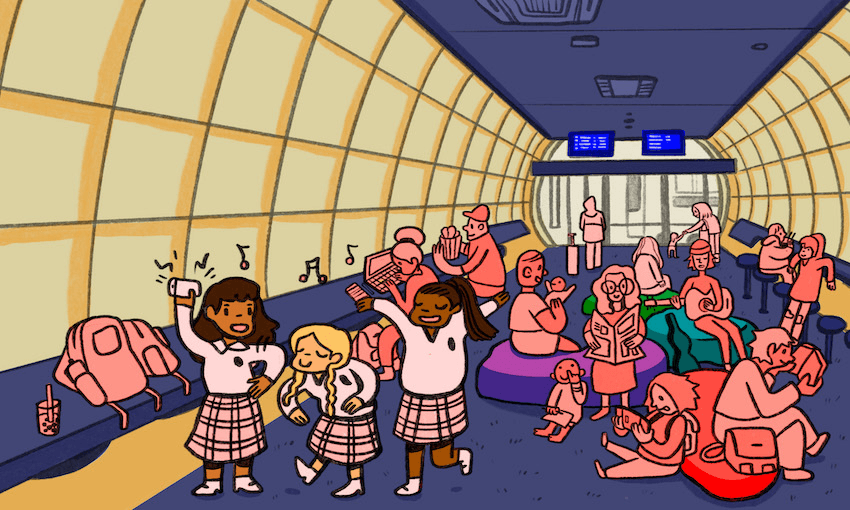

Original illustrations by MK Templer.

Once upon a time, before earthquakes and racism became Christchurch’s more prominent correlations, there was a Christchurch that was simply the place I lived and nothing else. The worst thing to have happened to the city in its recent history was not a terrorist attack or a natural disaster but Bunnings sausage sizzle prices going up from $1 to $1.50. These were the days of MSN and Nokia phones, Urban Angel and hot pink Supre tote bags – the years 2007 to 2011 – the perfect time for the city’s life and my own life to overlap.

I had a very wholesome time as a teenager in Christchurch. My equally wholesome friends and I eventually graduated from going to Riccarton Mall to going into town, where we scoped out new things to do. This mainly meant finding new places to sit without paying, or paying very little. We would have picnics in Hagley Park, film stupid videos in the Canterbury museum and people watch in Cathedral Square. We had no problem passing time, boredom was something that didn’t exist yet. When it was hot enough, we would head out further to the beach at Sumner. Staring out to the sea, we’d eat ice cream and talk as the sun slid across the sky, our hopes for the future and opinions of Matt’s new haircut having equal weight.

There was a place common to all of these outings, bookends to each lazy weekend. It’s the place that I still think of first when someone mentions Christchurch. A place that unlike Hagley Park, Sumner beach, or the Canterbury museum, is no longer around. It’s the original bus exchange on the corner of Colombo and Lichfield Street.

Since we couldn’t drive, my friends and I would always take the bus to get to and from town. Meeting up with everyone else before heading into the city on foot, or to pile on to a new bus out to the beach, was an essential part of the journey, a mini-outing in itself. Apply this to every group of teenagers getting across the city, and you can begin to imagine the life that teemed in the original bus exchange. It was the unplanned heart of the city, a place that was always popping, day and night.

Design-wise, there was nothing special about it. The bus exchange wasn’t really a standalone affair, more of a sandwiched form between and inside some other nondescript buildings. It was two-storied, with a food court on the top, a main waiting area on the ground floor, and a smaller waiting room by the Colombo Street bus stops. This on-street waiting space was the most creatively ambitious aspect of the exchange. It had become quite dark and dingy, but it was obvious that it was once someone’s hopeful attempt at modernity. Their vision: curved walls of softly lit semi-opaque white panels, and rainbow-coloured plastic blobs for furniture. With a good scrub and more light, the room could have been the backdrop to any 2000s music video.

Of the less exciting main waiting area, I remember non-descript blue carpet and rows of laminated MDF chairs shaped like this:

Along these rows sat old women with Ballantynes bags, young people in hoodies, young people in public school uniforms, young people in private school uniforms, unhoused people, lone dads in fleece, skateboarders, fast food employees, your hairdresser, your maths teacher, your mum’s friend from church. Everyone. People also sat on the floor – there was a rather permanent circle of Unlimited (an independent high school) kids who were usually found on the second floor. We never spoke to them, but would walk past with curiosity. In their perpetual mufti, they represented a whole different way of living.

Ambience at the bus exchange was largely provided by teenagers playing music from their cell phones – Sean Kingston, My Chemical Romance, and Crazy Frog by way of a Youtube to MP3 converter. TV screens with bright blue backgrounds and bright yellow text were dotted across the two floors, fortuitously telling of the comings and goings of all the buses in the area. They were important messengers – revealing who would have to wait for their bus the longest and on their own. Smells from the adjoining food court would enter into the space, accented by people who had brought their KFC snack boxes downstairs to eat in the open. People would be talking to their friends, or on the phone, singing along to aforementioned cell phone music, or be the occasional yeller. It was a cobbling together of mild sensory attacks. It sounds absolutely disgusting now but to a wide-eyed, Cool Charm-scented teenager, it was the centre of the world.

A SELECTION OF MEMORIES

1. A group of about 20 of us head out to Sumner, a trip for the international exchange students from Argentina, Germany, Thailand and Japan. It’s an endless day, the water is warm, no bad thoughts exist in our company, the sun is a giant golden disc, etc. As night falls we return to the exchange. Unwilling to go home we linger on the floor, talking, laughing and singing along to a guitar strum by one of the Argentines until the last buses of the night.

2. We strike up a conversation with a group of unknown boys in the row in front of us. We have all just watched a set of Smokefree Rockquest heats. They turn around in their seats, cute and talkative. We “discuss music” and feel like we’re on the brink of a new world. There are only a few months of high school left. On Monday, the boys at our own school appear even more boring than usual.

3. Two of us take the bus into town at lunch, our free period giving us two hours off. The exchange is calmer than on the weekend and we feel like we’re bunking. We find a small cafe down a brick alley that we’ve never come across before and share cake and cappuccinos, like adults, we supposed. It’s just us, town is quiet, things feel like they’re just around the corner, and we’re right.

In 2011, I moved to Dunedin for university and went from obliviously annoying high school student to obliviously annoying first year. The February 22 earthquake hit a few hours before the toga party. The projector screen in the dining hall was pulled down to play the news on loop, and we watched the helicopter shots of the cathedral rubble as we ate yoghurt. The kitchen staff told us it would line our stomachs against alcohol. Christchurch already felt a world away.

The original bus exchange was eventually demolished. The new one opened in 2015, located on the other side of Lichfield Street. With its huge fuckoff roof, huge windows and composite wood panels, the new bus exchange was – for better or for worse – an instant poster child for contemporary New Zealand architecture. What was definite was that it was completely different from its predecessor.

The first time I visited the new bus exchange in person, sometime in 2016, I was struck by how empty it was. The new layout saw people peel off into little nodes to wait for their bus, whereas the old layout had everyone sitting together in a big chunk in the middle, and the buses would arrive around the big communal chunk. The result was that the few people that were there when I visited were all seated apart from each other in a space too vast for connection.

The floor inside was concrete – like its exterior, on trend. It also added a cold echo to an already cold automated voice-over, which on my visit was the main source of noise. I kept thinking of the old occupants and activities that were missing, and not liking the new building at all. But it was 2016 now, no one was playing music on their cell phones in the Christchurch bus exchange because no one was doing that anywhere. The old women with Ballantynes bags were either dead or in Merivale, the dads in fleece relocated to offices in Addington. And besides, there wasn’t the same draw to the city yet. Shops and businesses hadn’t recovered and reopened at this point – there weren’t enough places to attract the same number of people.

I paid a fare almost double what I paid before the quake to get the bus back to my parents’ house and it felt true that things had changed. I’d already grown distant from the friends I used to meet up with every weekend. We had nothing in common any more and Matt’s haircut was no longer enough to sustain us. Earthquake or no earthquake, the Christchurch I like to remember the most was never meant to last beyond high school. It is a Christchurch completely coloured by nostalgia, unattainable not just because the physical markers are gone but because it can only exist in the past. Maybe there are teenagers today who are fusing their own memories with the new bus exchange. They’ll return years later to the clean, smooth, building, and wonder if the seats had always looked like that, if it had always been this dim, and how they as a person had once enjoyed this place.

This essay is set to appear in the forthcoming collection, Ōtautahi Explorations (Freerange Press).