It was the browser that most of us grew up with, and it survived for almost three decades despite competition from faster, sleeker and more secure rivals. But now Internet Explorer has finally been put out to pasture – and not before time, write a group of cybersecurity experts.

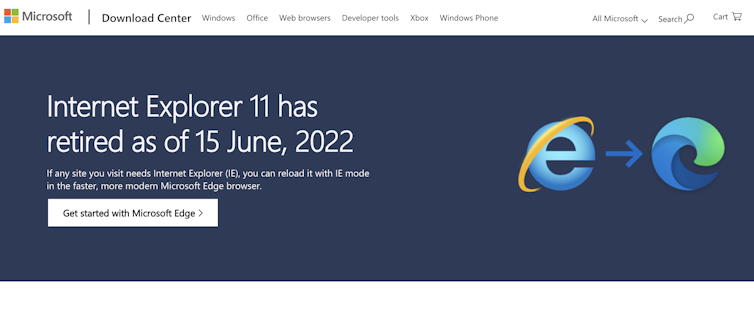

After 27 years, Microsoft has finally bid farewell to the web browser Internet Explorer, and will redirect Explorer users to the latest version of its Edge browser.

As of June 15, Microsoft ended support for Explorer on several versions of Windows 10 – meaning no more productivity, reliability or security updates. Explorer will remain a working browser, but won’t be protected as new threats emerge.

Twenty-seven years is a long time in computing. Many would say this move was long overdue. Explorer has been long outperformed by its competitors, and years of poor user experiences have made it the butt of many internet jokes.

How it began

Explorer was first introduced in 1995 by the Microsoft Corporation, and came bundled with the Windows operating system.

To its credit, Explorer introduced many Windows users to the joys of the internet for the first time. After all, it was only in 1993 that Tim Berners-Lee, the father of the web, released the first public web browser (aptly called WorldWideWeb).

Providing Explorer as its default browser meant a large proportion of Windows’s global user base would not experience an alternative. But this came at a cost, and Microsoft eventually faced multiple antitrust investigations exploring its monopoly on the browser market.

Still, even though a number of other browsers were around (including Netscape Navigator, which pre-dated Explorer), Explorer remained the default choice for millions of people up until around 2002, when Firefox was launched.

How it ended

Microsoft has released 11 versions of Explorer (with many minor revisions along the way). It added different functionality and components with each release. Despite this, it lost consumers’ trust due to Explorer’s “legacy architecture” which involved poor design and slowness.

It seems Microsoft got so comfortable with its monopoly that it let the quality of its product slide, just as other competitors were entering the battlefield.

Even just considering its cosmetic interface (what you see and interact with when you visit a website), Explorer could not give users the authentic experience of modern websites.

On the security front, Explorer exhibited its fair share of weaknesses, which cyber criminals readily and successfully exploited.

While Microsoft may have patched many of these weaknesses over different versions of the browser, the underlying architecture is still considered vulnerable by security experts. Microsoft itself has acknowledged this:

… [Explorer] is still based on technology that’s 25 years old. It’s a legacy browser that’s architecturally outdated and unable to meet the security challenges of the modern web.

These concerns have resulted in the United States Department for Homeland Security repeatedly advising internet users against using Explorer.

Explorer’s failure to win over modern audiences is further evident through Microsoft’s ongoing attempts to push users towards Edge. Edge was first introduced in 2015, and since then Explorer has only been used as a compatibility solution.

What Explorer was up against

In terms of market share, more than 64% of browser users currently use Chrome. Explorer has dropped to less than 1%, and even Edge only accounts for about 4% of users. What has given Chrome such a leg-up in the browser market?

Chrome was first introduced by Google in 2008, on the open source Chromium project, and has since been actively developed and supported.

Being open source means the software is publicly available, and anyone can inspect the source code that runs behind it. Individuals can even contribute to the source code, thereby enhancing the software’s productivity, reliability and security. This was never an option with Explorer.

Moreover, Chrome is multi-platform: it can be used in other operating systems such as Linux, MacOS and on mobile devices, and was supporting a range of systems long before Edge was even released.

Meanwhile, Explorer has mainly been restricted to Windows, XBox and a few versions of MacOS.

Under the hood

Microsoft’s Edge browser is using the same Chromium open-source code that Chrome has used since its inception. This is encouraging, but it remains to be seen how Edge will compete against Chrome and other browsers to win users’ confidence.

We won’t be surprised if Microsoft fails to nudge customers towards using Edge as their favourite browser. The latest stats suggest Edge is still far behind Chrome in terms of market share.

Also, the fact Microsoft took seven years to retire Explorer after Edge’s initial release suggests the company hasn’t had great success in getting Edge’s uptake rolling.

Only some Microsoft operating systems (mainly server platforms) will continue to receive security updates for Explorer under long-term support agreements.

Screenshot

What’s next?

Web browsers play a vital role in establishing privacy and security for users. Design and convenience are important factors for users when selecting a browser. So ultimately, the browser that can most effectively balance security and ease of use will win users.

And it’s hard to say whether Chrome’s current popularity will be sustained over time. Google will no doubt want it to continue, since web browsers are significant revenue sources.

But Google as a corporation is becoming increasingly unpopular due to massive data gathering and intrusive advertising practices. Chrome is a key component of Google’s data-gathering machine, so it’s possible users may slowly turn away.

As for what to do about Explorer (if you’re one of the few people that still has it sitting meekly on your desktop) – simply uninstall it to avoid security risks.

Even if you’re not using Explorer, just having it installed could present a threat to your device. No one wants to be the victim of a cyber attack via a dead browser!

Mohiuddin Ahmed is a lecturer in computing & security, M Imran Malik is a cybersecurity researcher and Paul Haskell-Dowland is professor of cybersecurity practice at Edith Cowan University in Western Australia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.