The minerals sector is highly volatile, highly competitive and changing rapidly, and the most obvious rationale for expansion – that it will provide a boost to national and regional economies – is certainly not a given.

Shane Jones’s mining boosterism has regenerated a seemingly perennial debate around the industry and the sector. As Sefton Darby noted in a Spinoff piece in 2017, successive governments over the past decades have made a point of reversing the stance towards and the policies of the previous crew – and the current coalition’s reversal of Labour’s ban on offshore oil and gas exploration is another example of the continuation of this trend.

The current round of reversals from Jones has also seen a revised draft minerals strategy, a resurvey of the country’s mineral endowment, the development of a draft list of “critical minerals”, and inclusion of 19 mining and quarrying projects on the initial list under the government’s fast-track legislation.

Jones’s ambition – to create 10 significant new mines and a doubling of export values within the next 10 years, and reestablish mining within the culture of regional NZ in particular – and his almost boyish enthusiasm (a master of triggering hyperbole, he has already suggested that blind frogs called Freddy had better watch out for the expansion of the industry) has provoked the expected response from environmental and community groups. Similar moves under the Key government in 2010 produced some of the largest protests seen in the last two decades.

This time around there has already been widespread opposition expressed through the media, protests around new exploration targets in Tasman District and Central Otago (see here and here), including from high-profile winemakers and celebrities (such as Sam Neill) and, in a very different setting, student protests around the Career Expo recruitment efforts of the Australian mining sector at Victoria University (see the debate between Martin Brook, a geologist at Auckland University who took particular exception to the latter, and the response from the organisers).

What the current debate has exposed is a poor understanding of the industry and the opportunities and challenges it presents, and no clear sense of how it can contribute effectively to Aotearoa’s future. So what does international experience tell us about the sector – what can we really expect from an expanded mining industry, and against what conditions should this expansion be evaluated and permitted?

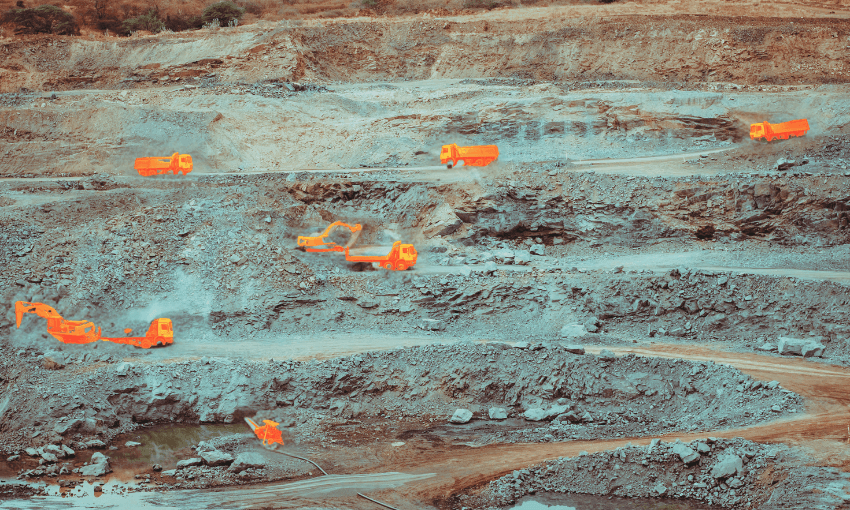

First, the most obvious rationale for the sector – that it will provide a boost to national and regional economies – is certainly not a given. Indeed, the returns are probably not likely to be what the minister would like. By its very nature the contemporary mining industry is (imported) capital-intensive and a relatively small employer of a mix of highly skilled tradespeople and more traditional roles (such as the dump truck drivers). The Victoria University economist Geoff Bertram carried out a detailed analysis during the last flurry of National-government interest in the sector and found that the share of the value of the resource the country receives is relatively low. And the small workforce similarly means that salaries and wages form a low proportion of the gross value-add from the sector.

At this point, it is worth quickly pointing to the differences between New Zealand and Australia in terms of the mining sector, wealth and the economy, a comparison that is often made to support the case for why we should be doing more to free up our mineral resources. We know that Australia is a much more heavily minerals-dependent economy, but I doubt many of us realise just how much so: New Zealand mineral exports were worth just over NZ$1bn in 2022, while in the same year Australia’s mineral exports from more than 350 operating mines topped A$400bn.

There are two ways to look at this disparity – one is that NZ should be exploiting its mineral wealth if it wants to get closer to parity with Australian levels of wealth and standards of living. The other would perhaps recognise that mineral wealth might not be the key element in the disparity if it takes more than 400 times the value of mineral exports to produce the 30-50% differences in GNI/capita and incomes between the two countries.

The reasons for this are complex and varied. One of the most significant is the highly volatile nature of the minerals sector. Gold is a lovely case in point: the table below illustrates this with reference to the price of gold – up by 371% in the decade 2001-2011 and down by 7% in the following decade – with significant peaks and troughs within each of these decades. Most recently the price of gold has taken off again, trending up by more than 30% in the year to early November.

An even more spectacular rollercoaster is illustrated by the green transition mineral lithium. Due to new deposits and sources of supply appearing rapidly in recent years, the metal has lost 90% of its value in the last two years from the peak in December 2022, which itself was a staggering 1,350% increase on two years earlier (Dec 2020). Booms, busts and the constant search for the “motherlode”’ of value are still defining characteristics of the sector.

Large-scale contemporary mining is complex to operate and to regulate, govern and even tax effectively. Again, we can legitimately ask whether – even before the significant cuts in personnel and resourcing – the public sector had the regulatory capacity to facilitate the development and effective and safe operations of anything like the 10 significant new mines the minister would like to see in place within the next decade.

The sector is also highly competitive and changing rapidly. The regulatory “opening up” of new countries and areas for exploration and mining (such as Jones is attempting to do for Aotearoa) has seen countries globally tinkering with the regulations and requirements around mining, all with the intent of attracting further foreign investment. This has created a drawn out, global “race to the bottom” in terms of “freeing up” the environmental, fiscal and social regulation of the sector. The reduction of regulatory and approval oversight contained in the fast-track legislation appears to be Minister Jones’s contribution to this race.

The minister’s references to the need for New Zealand to “do our bit” in terms of the production of “critical minerals” is used as an additional justification for the expansion of the sector. The problem is that none of the evidence to date – over a hundred years of sporadic and the more recent systematic surveys – indicates that we have significant, world-scale reserves and resources of any of these critical minerals. There are potentially reserves of antimony on the West Coast, and exploration interest in lithium in a few spots, but nothing like the scale elsewhere. And the argument that we have a moral obligation to produce some of what we consume in terms of the critical minerals we draw on in our everyday lives just doesn’t hold water in the globalised world we live in. The label “critical minerals”, then, is just being used as a discursive shift to try and justify the continuing relevance of the mining sector and open up new opportunities for the expansion of non-critical minerals (such as gold) and fossil fuels (coal).

Mining by its very nature transforms landscapes – physical and social – and despite much progress and improvement in social and environmental management of the effects of mining, it continues to be a sector that is bedevilled by environmental legacies and more recent disasters, acts of cultural destruction, and an oftentimes wilful disregard for communities and governments.

So yes, we cannot wish away mining, and indeed we can embrace it or at least learn to live with it. But what we can wish for is a sector that meets the expectations and standards of the 21st century. Betram’s warning from 10 years ago is equally apt today:

Mining will not increase economic welfare – on the contrary, it will often reduce it – if done in the wrong place, or in the wrong way, or without a proper legal and regulatory framework. Mining therefore presents industry-specific problems for regulators and policy makers, which cannot be finessed by overgeneralised rhetoric or glamorous photography.

A sector that is led by Shane Jones’s hyperbole and industry boosterism will be damaging to the country, its people and its landscapes, all for little or no return.