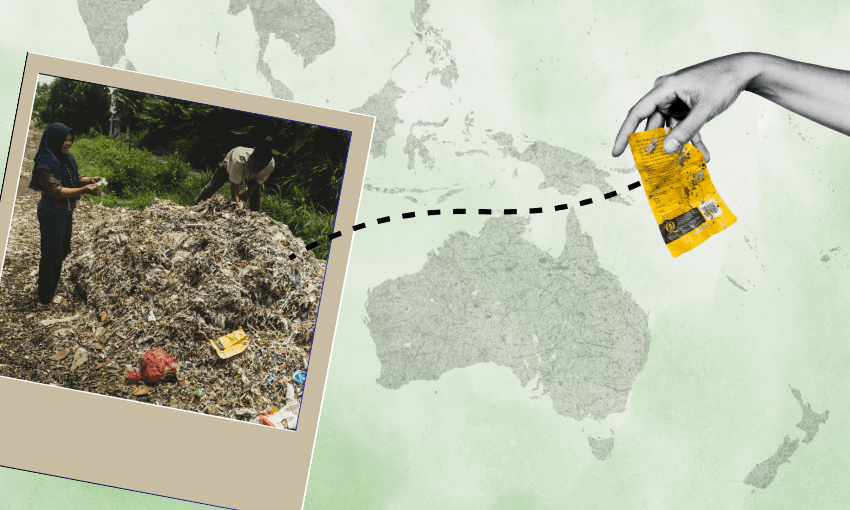

New Zealand sends most of its recycling offshore, to places like Indonesia and Malaysia. Michael Neilson visits the communities dealing with the consequences.

In a tiny village in East Java, Indonesia, two children laugh as they tumble down small piles of what could easily be autumn leaves in New Zealand, playfully throwing handfuls at each other. Except it’s not leaves that crunch beneath their feet, but millions of tiny pieces of plastic scrap originating from all over the world, including New Zealand.

Outside almost every home in the village of Pagak are small hills of plastic scrap, originating from wastepaper imports contaminated with plastic. After China’s ban on waste imports in 2018, Indonesia has risen rapidly to become one of the world’s top recipients of wastepaper for recycling, taking in about three million tonnes a year, according to its Bureau of Statistics.

More than half of New Zealand’s wastepaper for recycling is sent offshore. In 2024, New Zealand exported 259,000 tonnes, with the majority – about 150,000 tonnes – going to Indonesia. The country has a 2% contamination limit for imports, but local environmental organisation Ecoton says it has found contamination up to 30%. This contamination generally occurs due to poor sorting before export.

After the wastepaper bales arrive at Indonesia’s paper mills and are processed, this plastic, generally dirty and low-grade, such as pet food packaging and baby food pouches, is separated and provided to communities near the facilities. Local workers sort through it to find any remaining wastepaper that can be sold back to the recyclers, with the remnants burned.

While most of the plastic is unrecognisable due to degradation, it doesn’t take long to spot items from all over the world: a coffee bag from France, beer packaging from Australia, and even a Pams 1kg sugar wrapper with “Made in New Zealand” proudly displayed on the front.

Nearby the playing children, their mother Hamidah and grandmother Marsiah are bent over in the sweltering midday heat, sifting through the plastic for any tiny pieces of paper and cardboard that might not have been successfully separated from the scrap plastic before it was given to the communities. They dry out any remnants found before reselling to the paper mill.

The family, one of about 900 households in the wider area that receives scrap plastic from the mill – there is even a waiting list – say they make about NZ$100 a month, which supplements the crops they grow.

Also in the village is a giant open limestone kiln, where several men tend to a huge fire they say is burning 24/7 to soften the stones above. It’s fuelled entirely by the same imported scrap plastic. Kreteks, or clove cigarettes – a staple of Indonesian culture – hang out their mouths, also burning constantly, the sweet cinnamon smell balancing the thick, acrid black smoke from the fire that pierces nostrils and makes eyes water, as those very children play on the street just metres away.

These fires are known to emit alarming levels of dioxins and hazardous chemicals and ultimately infiltrate human food chains, including through the ash, causing respiratory diseases, hormonal imbalances, and reproductive disorders. Another kiln site, visited by The Spinoff, has a football-field-sized pile of plastic ash along the Brantas River, which supplies irrigation and drinking water.

“It’s tiring and dirty and very low paid, but there are few opportunities here,” says Ahmad Yani, a waste collector himself and waste management activist for the village. He says people are not aware of the health risks of burning plastic and microplastic contamination, but he doubts there would be resistance if the government tightened regulations. “They just want jobs.”

Further north in the town of Tropodo, thick black smoke fills the horizon also, but this time it is emanating from the 60 tofu factories in the area. Tofu producers collect this same type of scrap plastic from other paper mills nearby – also reliant on wastepaper imports – and burn a trailer load daily to cook soybeans.

A local tofu factory owner says they have used plastic fuel since about 2010 because it is free and burns easily, as opposed to wood and gas. He switched to a combination of plastic and coconut husks in the past few years, but not for health reasons, rather so the smoke would be less black and attract less attention from authorities. Uncontrolled burning of plastic is illegal in Indonesia, but regulations are rarely enforced.

Tests by East Java environmental group Ecoton found microplastics in tofu from nearby markets. Ecoton was involved in a multinational 2019 study of eggs taken from chickens that roamed through the plastic ash sites at Tropodo, which revealed that eating just one of these eggs could exceed the European Food Safety Authority’s safe dioxin intake by 70 times. A 2024 study that included other sites in West Java returned similar results.

“Dioxins from burning plastic accumulate in the environment and enter the food chain,” says Dr Daru Setyorini, Ecoton’s executive director. “These chemicals persist in the body and cause long-term damage.”

Despite Indonesian authorities pledging investigations, Setyorini says public awareness remains low. “Most people don’t know what microplastics are, let alone how harmful they are.

“My message to the developed countries is recycling is not effective. They should not burden developing countries to manage the rich countries’ waste.”

In neighbouring Malaysia, the situation is equally dire. This is where most of New Zealand’s plastic recycling ends up. Once a minor player in the global recycling industry, Malaysia became the world’s top importer of used plastic after China’s ban on waste imports in 2018. Before the ban, it imported 200,000 tonnes of plastic waste per year. By 2018, that number had soared to over 800,000 tonnes, prompting government crackdowns.

New Zealand’s Ministry for the Environment estimates that about 55,000 tonnes of plastic are collected for recycling in New Zealand each year, with around half exported. Customs data shows New Zealand’s plastic waste exports are decreasing, from about 50,000 tonnes in 2016 to just over 27,000 tonnes last year.

In 2024, about 15,000 tonnes went to Malaysia while Indonesia received just under 6,000 tonnes. Indonesia has this year implemented a ban on plastic waste imports, which campaigners fear will see an increase to Malaysia.

Each New Zealander sends about six kilograms of plastic waste overseas annually, three kilograms of which go to Malaysia. Like with paper, a legitimate global plastic recycling industry exists, as long as the materials are clean, sorted and of a high standard – such as clean plastic bottles and containers, generally made from polyethylene terephthalate (PET or number 1) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE or number 2).

Last year, New Zealand introduced standardised kerbside recycling rules across the country, including narrowing plastics accepted to types 1, 2 and 5. These higher-grade plastics can be recycled into new products, and in many cases end up back in New Zealand. The global Basel Convention since 2020 also introduced tighter rules around exporting low-grade and mixed plastic.

But even this recycling process concentrates dangerous chemicals into the new products and releases microplastics into the environment. Activists argue that much of the exported plastic waste ends up in places chosen for their lax environmental laws and cheap labour.

Pui Yi Wong, a Malaysian campaigner with the Basel Action Network, says the recycling industry in her country is way overcapacity and they regularly discover illegal dumps of contaminated foreign plastic waste.

“It makes us very, very angry. It’s a matter of justice. Why do we need to take in all this waste?” she asks. “Your countries have the resources. Why are you sending it here?”

Wong says it comes down to economic incentives. “They say, ‘It’s for the global circular economy,’ but really, why is it cheaper? Because utilities are cheaper, wages are lower, and laws are weaker.

“Workers lack personal protective equipment and risk their health to process waste for the so-called circular economy.”

Despite those Basel Convention regulations, illegal imports to Malaysia of shredded plastics, often from electronic waste, are increasing. Since 2021, such waste has been dumped in urban and rural areas, palm oil plantations, and residential neighbourhoods.

Grace Foo and Mei Fang in the village of Selangor, an hour south of Kuala Lumpur, live with the consequences. Near their apartments, plastic waste is burned daily, filling the air with toxic smoke.

Foo, a breast cancer survivor, fears he health effects. “We cannot even open our windows,” she says. Fang says her young son developed nosebleeds after they moved to the area. “We just want fresh air. If we can’t have the right to breathe clean air, what is our human right?”

Malaysia’s environment ministry did not respond to requests for comment.

In Indonesia, meanwhile, the government has sought to tackle plastic waste imports but not wastepaper. Its ban of plastic waste imports follows a similar ban in Thailand.

Novrizal Tahar, Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment director of waste management, says the ban on imports of plastic scrap will encourage the use of domestic plastic scrap in the recycling industry. Asked about plastic contaminants in paper imports, Tahar says the ban will also encourage recyclers to use all available plastics.

On the health impacts of current local disposal methods, Tahar says the ministry is communicating these concerns to local governments and will take enforcement action if necessary.

The Indonesian Plastics Recyclers Association and Indonesia Pulp and Paper Association did not respond to requests for comment.

Barney Irvine, coordinator of New Zealand’s Waste and Recycling Industry Forum, which represents the companies contracted by councils and other bodies to deal with recycling collected at kerbside and elsewhere, says that exporting post-consumer plastic is becoming more restricted.

“There are greater restrictions on what kinds of plastic can be exported and where, and major shipping lines are increasingly less willing to transport it.”

On reports of contamination in Indonesian paper mills, he says the industry takes its responsibilities “very seriously”. “We aren’t aware of New Zealand waste being dumped near factories,” Irvine says. “If such cases exist, we would be concerned.”

Where the forum’s members sell waste recycling directly to importers, they will visit the sites to ensure the materials are being handled responsibly, says Irvine. Where they sell via brokers, they are careful to only use “well-established, reputable players”, he says. There are also licensing and inspection regimes, and if the exports don’t meet the threshold they are rejected, he adds.

But campaigners in Indonesia and Malaysia say those regulations are not always enforced. The New Zealand Government has also admitted it has no idea what actually happens to recycling once it leaves the country.

New Zealand waste management campaigner Lydia Chai says while she believes most New Zealand exporters meet contamination thresholds, much could go wrong after the shipments leave the country.

“Once it leaves our shores, it is wishful thinking that we can monitor the final destination of a plastic bale,” she says. “If we cannot deal with the waste ourselves then surely the most logical thing is to significantly reduce the plastic that enters the country.”

In 2023, Chai petitioned the then Labour government for a ban on plastic waste exports to developing countries. It received the signatures of more than 11,500 people.

The Environment Committee recommended the government set a deadline to phase out unlicensed exports of plastic waste to countries beyond Australia, and develop a more comprehensive policy to avoid the creation of plastic waste. The new National-led government rejected the petition, saying a ban would be “challenging and risky” and it would instead focus on border controls and compliance.

The government has previously said it relies on exports because it lacks the infrastructure to recycle onshore. If it stopped exporting the waste it would simply go to landfill, Ministry for the Environment director of waste and resource efficiency Glenn Wigley has previously said.

The ministry does not hold up-to-date data on New Zealand’s recycling rates. In a statement, a spokeswoman said it was likely domestic recycling was increasing, as plastic exports had nearly halved since 2018 and new recycling facilities had opened.

Environment minister Penny Simmonds says issues to do with recycling contamination are the responsibility of exporters and the importing country. On environmental and health concerns, she says those are also the responsibility of the importing country.

Asked about any actions New Zealand was taking to address concerns about waste exports, Simmonds says the government will be consulting this year on waste legislation reform proposals. Those proposals, released this month, do not mention waste exports.

Green Party spokesperson for zero waste Kahurangi Carter says the party is disappointed the government rejected the petition and “incredibly concerned” about the potential environmental and health impacts of waste originating in New Zealand.

“Successive governments have created a system where corporations extract resources, make disposable products, and then abdicate responsibility by exporting waste offshore,” she says.

“What we need in Aotearoa is greater investment into infrastructure that will enable greater resource recovery and reuse and greater ambition to accelerate towards a circular economy, where single-use plastics are eliminated as much as possible.”

Meanwhile, in Malaysia, the campaigner Wong says the “injustice of waste colonialism must end. New Zealand must take responsibility for its waste and ensure it is managed within its borders. There is a consequence for convenience that someone is paying for – even if they are not the ones using the plastic.”