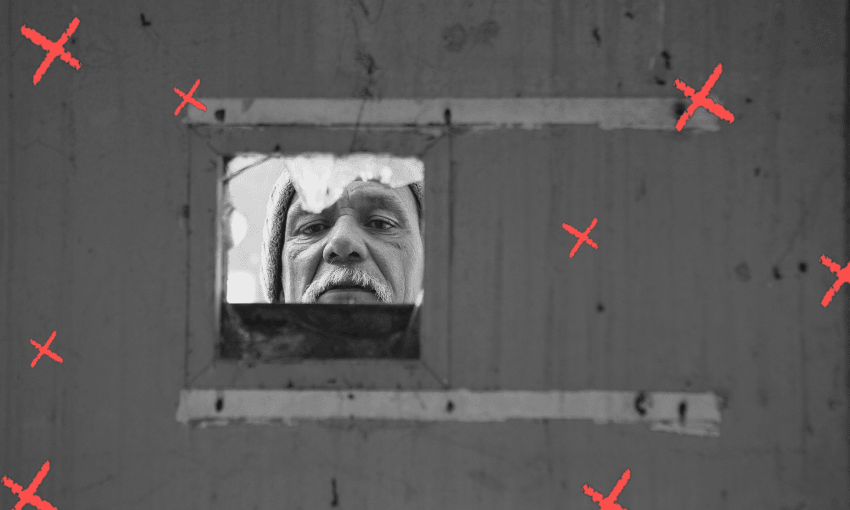

A new documentary from investigative journalist Aaron Smale details the abuse of hundreds of thousands of New Zealanders in care, and the long shadow it casts over our nation.

In July 2023, the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care released its final report, confirming what survivors had long known: that more than 200,000 people – many of them children – were abused, tortured, or neglected while in the care of the state or faith-based institutions in Aotearoa. It was a historic milestone in a decades-long fight for truth and justice.

But how do you begin to tell the story of that abuse? How do you capture the scale of a system that chewed through generations?

Journalist Aaron Smale, producer of The Stolen Children of Aotearoa, likens the task to “putting your hand into a silo of grain and pulling out a handful”. His 106-minute documentary, produced in partnership with Awa Films, does not attempt to offer a neat or complete summary. Instead, it provides a confronting and emotionally wrenching platform for those who lived through it.

The documentary opens with survivors sharing tender, early memories – snapshots of childhood before the system intervened. While some speak of hardship, there’s a shared sense that being taken into care was not only unnecessary, but deeply damaging.

The disproportionate numbers of those taken being Māori was no accident. Smale traces this violence back to its roots – not in the formation of social welfare departments, but in colonisation itself. He uses the 1994 film Once Were Warriors as a provocation: how did Māori go from living in rural, functioning communities to the trauma and dislocation depicted in that film?

To answer that, The Stolen Children moves through history. The British arrival. The wars. The land loss. Māori participation in the second world war and the effects of postwar dislocation. The late Bom Gillies, the last member of the Māori Battalion, recalls comrades returning home from Europe to a country that no longer felt like theirs – “a lot of them turned to grog”, he says.

And then came the policies. Urbanisation. Child welfare interventions. Institutionalisation. Abuse.

What emerges is a clear connection: colonisation never ended. It simply changed form.

One of the most compelling features of the documentary is how it traces the path of state control – from care, to youth justice, to adult prison, to the mental health system. Archival footage underscores the attitudes that allowed this system to flourish, but it’s the testimonies of survivors that hit hardest.

We follow a handful of them closely: taken into state care as children, shunted between homes, locked up, medicated, beaten, sexually assaulted. For many, it ended in gangs – not always out of a sense of belonging, but often out of pain.

“I never joined the gang for brotherhood or family,” says Milton, one of the film’s most compelling voices. “I joined for nothing else but the chaos and the anarchy. Because now, it was payback time.”

It’s a pattern repeated throughout the film: state-sanctioned trauma leads to criminalisation, which leads to further punishment.

Among the most disturbing chapters is the film’s treatment of Lake Alice psychiatric hospital. Survivors describe being subjected to electroconvulsive therapy by Selwyn Leeks, who oversaw the adolescent unit in the 1970s. It is described as torture. Leeks died before he could be held to account.

What’s most troubling is how normalised this abuse was, how many people looked away.

The final section of the film centres on the long, exhausting fight for justice. It covers the Royal Commission, the Crown’s eventual apology, and survivors’ frustration with the lack of tangible outcomes.

For many, the apology rings hollow. Thousands of survivors have since passed on, their whānau unlikely to ever receive acknowledgement or compensation.

What justice means in this context is not always clear – but it clearly isn’t what’s currently on offer.

The Stolen Children of Aotearoa is raw, unflinching, and necessary. Smale centres survivors without sanitising their stories, and weaves together history, testimony, and systemic critique in a way that honours the complexity without losing coherence.

There are moments where the number of voices and historical layers can feel overwhelming – but perhaps that’s the point. This was overwhelming. It still is.

By the end, I was shaken, angry, and grateful. Grateful to those who told their stories. Grateful for the upbringing I had – flawed as it was, it was nothing like this.

This is not an easy watch. But it’s an essential one.

The Stolen Children of Aotearoa premieres tonight at 8.30pm on Whakaata Māori and will be available to view on Māori+.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.