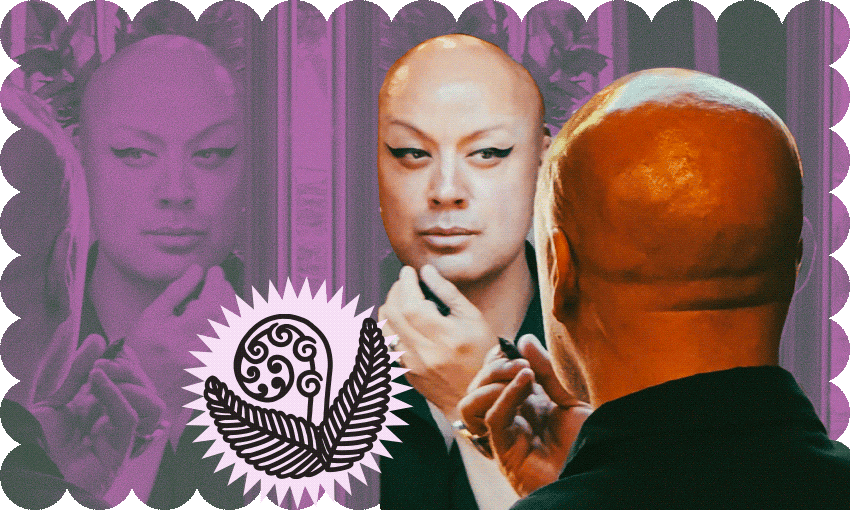

The multidimensional fa’afafine artist has created art to bridge her many identities – and to survive. Nearing 50, and more at peace with her life, receiving The Arts Foundation’s first queer laureate award feels right.

Lindah Lepou no longer feels she has to fight to survive, but it’s taken almost 50 years to get here. She’s content, she says, with the many lives she’s lived since she was born in 1973. And now the multidisciplinary fa’afafine artist begins another life, as New Zealand’s inaugural queer arts laureate.

This year, for the first time ever, The Arts Foundation Te Tumu Toi presents the “Toi Kō Iriiri” queer arts award in celebration of an outstanding artist or group of artists whose practice has a meaningful impact on the queer community. Lepou, described by one of the selection panellists as an innovator and advocate who has “forged an inimitable reputation over her career”, is the maiden queer laureate.

It comes at a perfect time in her life where she feels strong enough within herself to bridge her contrasting identities: fa’afafine and Pākehā, fashion and art, masculinity and femininity, art and commerce, the non-physical and the tangible. “It’s like sitting in the eye of the storm where it’s the calmest. And I’m really comfortable there.”

She’s perhaps best known for her award-winning “Pacific couture”, a term she coined to define her dramatic, conceptually driven, one-off garments often made using Pasifika elements and traditional materials. Te Papa permanently holds many of her garments. She’s exhibited in the US, Russia, China and the UK, and alongside storied designers such as Christian Dior, Vivienne Westwood and John Galliano. Yet more than one dimension marks her oeuvre: multimedia, performance, choreography, acting, singing and songwriting, uniform manufacturing and costume design. Lepou is a multihyphenate – mostly because she’s had to be.

Born in Wellington to an absent Palagi father and solo Samoan mother, the effeminate Lepou was brought up in Cannons Creek, Porirua, surrounded by, in her words, a Palagi god and subtle conversion therapy, physical violence and sexual predators. One day after school, at the age of eight, she learned she was being sent to Samoa to live with her maternal grandparents. She ended up living there for 10 years, surrounded by more of the same trauma that she left behind in Aotearoa. At 17, she earned a scholarship to study business at Latter Day Saints private Brigham Young University in Hawai’i – except it was a “lion’s den for a young, fa’afafine girl”, she says, pronouncing girl like she would “curl”.

She would withdraw from the course and return to Samoa, where her grandmother was furious. A few weeks on, she found out a local fa’afafine beauty pageant would award the winner a plane ticket to New Zealand. “I knew instantly – that is my fucking ticket. I just went into this zone. I knew it was mine.”

And it was hers – she won the pageant, and returned to Wellington in 1992. A few months later, having stayed with religious family members, she was kicked out amid accusations she had touched one of the kids, allegations that blew her mind because “for us girls, we’re so fiercely protective over our young ones and the elderly”. Homeless at 18, she encountered a city rife with the persistent threat of sexual abuse, assault and harassment reserved for fa’afafine, takatāpui and the trans community. Survival became her third life. When she lived in Samoa, her grandfather warned her that he would drag her to another boy’s house and make her fight him again if she came home crying the first time, and that she would get a hiding if she didn’t win. The penny dropped when she found herself on her own in Wellington. “He prepared me, whether he was conscious of it or not,” she says.

As fa’afafine, Lepou was born male with her femininity “cranked up”. For girls like her in the early 90s, sex work was at the top of the jobs list, “especially if you couldn’t pretend to be masculine,” she says. “For me, personally, I was like ‘oh my god, I can’t even do that, I’d be fucking useless’.” Instead, she pursued fashion. For six months, she studied fashion design at the Bowerman School of Design, under the tutelage of its owner, Sue Bowerman. As Lepou entered class on the first day, she spotted another young girl like her, Raphael Thomson. “I went ‘who are you?’” she says, head turned to the side, chin down and eyes locked, mimicking the condescension that comes with meeting competition. “And then I went ‘what kind of men are you into?’ and she goes ‘caramel’. She was so terrified!” Thomson’s terror dissipated as soon as she started sharing her love for En Vogue and Janet Jackson – artists that Lepou loved too.

Thus, “Pure Funk” was born – a performing duo that grew into a trio with the addition of Ramon Te Wake, and then a quartet when Phylesha Brown-Acton joined in 1996, when the trio had moved to Auckland. The group was a “little mafia” of sorts, a safe and secure space that Lepou nurtured as its street-wise, homemaking “mother”, and a vessel for self-expression and creativity. Pure Funk was at the forefront of activity in the LGBT community, and pushing boundaries in the mainstream, Lepou says, recalling the time they strutted the catwalk at the “very white, very elitist” Trentham racecourse fashion show. It may have been another lion’s den, but “we just didn’t give a fuuuck because we felt safe, especially with each other.”

After some time in Auckland, and tired of the daily struggle of being misgendered by their banks or resorting to talking like men to get anything official done, the quartet went their separate ways. They were all ready to live their own lives, clear about their identities and goals, she says. “When we dispersed… we all knew this connection that we had was always going to be there.”

In 2017, 25 years culminated in fire. By then, Lepou was living in a cottage on the grounds of Government House in Wellington as the Matairangi Mahi Toi Artist in Residence, a scheme run by the office of the governor general and the Massey University College of Creative Arts. One night in October, there were “gasps and tears” at the governor general’s residence – an audience watched a video of Lepou on a beach throwing some of the iconic gowns created over the past 25 years onto a bonfire. She admits to not caring about preserving the end product of her work. “My creative process to the end, is where I’m really invested.”

A mound of ash and charcoal was left behind, the bonfire’s smoke having transformed Lepou’s Pacific couture into their first forms as “invisible monsters”; their non-corporeal bodies originating in her mind and shaped, sewn and woven into existence only by her bidding. She is the channel between the non-physical and the tangible, and critical to that is her wellbeing. “I can have a billion-dollar contract or whatever,” Lepou says. “[But] if I hate myself, it’ll fucking poison it all. It will all fall apart. So none of that stuff matters to me if my self-love is out of whack.”

Communing with her aitu, her “spirit guides and ancestors”, is another anchor point. “This is me talking to my aitu, ‘Are you fucking serious? Are you saying I’m here to fucking pay bills, bitch? Is that really what this is about? If so, then fucking take me now! This is pointless’.” Both touchstones speak to Lepou’s need for alignment – if something feels off, “I don’t get out of bed, I’m staying in my fucking pyjamas.”

Recognition ensued as early as 1994, when her design “Flax tutu” was runner-up in the Benson & Hedges fashion design awards. Originally placed in the avant-garde category, Lepou’s design spurred the homegrown fashion competition to create a Pacific and Māori fashion category the following year. Nearly 30 years later, Lepou is being recognised for forging a new path. The queer laureate award stands alongside the foundation’s existing slate of laureate awards, which recognise outstanding New Zealand artists making a meaningful impact. Green Party MP and artist Dr Elizabeth Kerekere (Ngāti Oneone, Te Aitanga a Mahaki, Whānau a Kai, Rongowhakaata and Ngāi Tāmanuhiri) gifted the queer laureate its Māori name, “Toi Kō Iriiri”, in reference to art that “moves us in or out of discomfort, but always to a new place”.

Made possible by recently appointed foundation trustee Hall Cannon, who has endowed Toi Kō Iriiri with $300,000 for the next 10 years, the award is accompanied by a $30,000 grant to fund their work. It’s difficult for Cannon, originally from Memphis, Tennessee, and who has called Aotearoa home since 2006, to imagine a world in which art doesn’t exist. “Artists have an ability to tell stories through their works,” he says. “And those stories are powerful – they open doors, they reveal our common humanity.” By 2032, 10 “legendary” queer laureates will have been recognised. And the first is Lepou. “She’s extraordinary,” he says. The selection panel found someone who has been an “active role model within the queer community, I’d say, since Lindah started breathing. She brings a lot of gravitas and mana to this role.”

Lepou is grateful for the individual recognition, yet when she was told about being the award’s inaugural recipient, she was transported straight back to her memories of her sisters in the LGBT community, “who are still unseen and just don’t even get fucking in the door, and have remained innovative though”. Being the first, she says, is “about me celebrating all those bitches that I know, who are fucking talented and innovative, fearless and remain true to who they are.”