An attempt to sell the Wellington City Council’s shares in Wellington Airport created a deep fissure within the Green Party, exposed fractures between councillors and staff, and started a high-stakes game of political horse-trading.

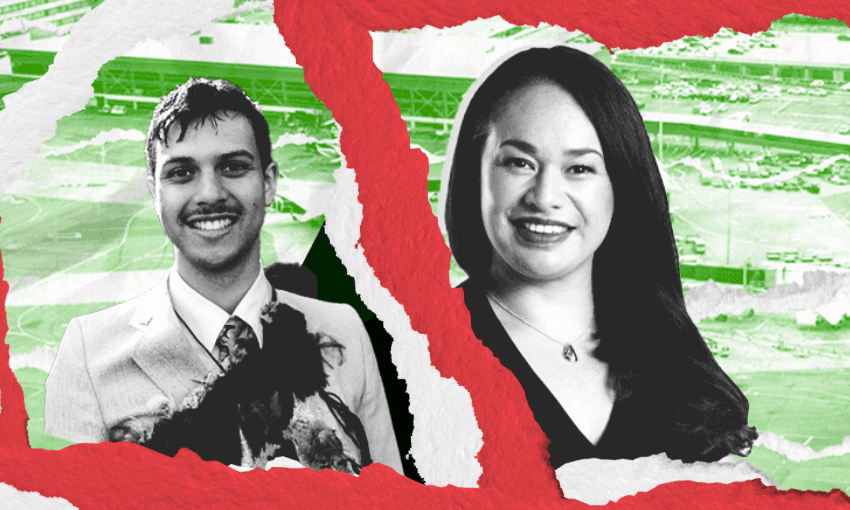

In the second instalment of a three-part series running this week, Oliver Neas explores the dramatic conflict and behind-the-scenes dealmaking that shaped the Wellington Airport saga. You can read part one here.

It was 30 May, 10.30am. On the 16th floor of a central Wellington high-rise, the meeting to decide the fate of Wellington Airport was under way. Nīkau Wi Neera, the first-term Green councillor, was standing at the council table, a sheet of paper in his hand. He cleared his throat and began to read. “We believe that public ownership is a crucial element of our mahi and we will always advocate for public collective ownership of assets and services. Many of our policies include advocating for public ownership whether it is our public transport system or the Wellington Airport.”

He tossed the paper behind him. “The words I just read come from the Greens’ local government charter for the local body election –“

“– Councillor,” interjected the meeting chair, Rebecca Matthews. “Councillor, could I just make sure that you don’t throw the pages behind you as there are people sitting behind you? Thank you.”

“I have no more pages to throw,” Wi Neera replied. Then, after a pause, “I signed up to those words, as did some others around this table. I believe the sale of Wellington City Council’s stake in Wellington International Airport Limited to be deeply, fundamentally wrong. The fact that an ostensibly progressive council would even entertain this notion is frankly shocking. If this is to be the new direction of the Green Party and its allies – the party who has never sold a public asset, the party who has always stood on principle, the party who has nurtured me and made room for me ever since I excitedly ran down to the Kāpiti Library with my ballot papers to cast my very first vote at the age of 18 – if this is the new direction of the party then I want no part in it.”

There were 18 people with votes in the room, but Wi Neera’s speech was mainly addressed to one of them: his Green Party colleague, mayor Tory Whanau.

Since her election to the mayoralty in 2022, Whanau had the steady support of a left bloc of Green and Labour councillors, which formed the council majority. But this alliance was under serious pressure following Whanau’s decision to back the sale of the council’s shares in Wellington Airport – a move that would make it the first major airport in the country to be fully privately owned.

Back in November, in a vote to consult the public on a sale, three of her Green colleagues had supported the idea. All had since come out against the sale. Loudest among them was Wi Neera.

Whanau’s relationship to the Green Party was, in fact, ambiguous. She had served as the party’s top parliamentary staffer for years, but while she had been endorsed by the party as a mayoral candidate, she had technically run as an independent and had since let her party membership lapse. But in April, the day after her meeting with Unions Wellington, she announced she had rejoined the party. In the weeks leading up to the crucial May 30 vote, Wi Neera dialled up the pressure to get Whanau to stick to what he saw as a core Green Party principle: public ownership.

He tried approaching the mayor directly, pitching an alternative solution he had devised to the council’s insurance problem, in which the council would keep the airport but direct revenue from the shares into a new self-insurance fund. The mayor’s office wasn’t interested.

Audaciously, he reached out to several Green MPs, asking them to sign an open letter to the mayor opposing the airport sale – a move which, in his words, “ruffled some feathers”. A meeting of the parliamentary Green caucus was called in response where, according to Wellington Central MP Tamatha Paul, it was “decided that this was a matter for Wellington City Council and that us taking a stance on it as a party was interfering in their business.”

Two days before the vote, Wi Neera went directly to the party membership, calling for an urgent meeting of local Green members. The party’s anti-capitalist wing – the Green Left Network – was firmly opposed to the sale, but the broader local membership was more divided, according to three people on the call.

As the vote loomed, it felt to Wi Neera like he was engaged in a “chess match” with the mayor’s team, each working late into the night to lobby their colleagues. Who would have the numbers? Late one night, he came out of his office to find the mayor shaking hands with right-wing councillors Diane Calvert and Ray Chung. “They all looked like deers in the headlights,” he recalled. “No one said anything. … It made my skin crawl.”

While his open letter gambit had failed, Wi Neera still had allies in parliament. The day before the vote, Tamatha Paul spoke out publicly, telling The Post that opposition to privatisation was “fundamental” to Green principles and that any Green elected member who voted for selling shares would “undermine the credibility” of the party and damage its relationship with unions.

The mayor seemed to be losing confidence, telling Newstalk ZB she didn’t think she had the votes for a full sale. But Wi Neera wasn’t sure he had the numbers either. The odds did, however, seem to be shifting in favour of the anti-sale camp; Iona Pannett, who was previously undecided, told The Post she was now “sympathetic” to Wi Neera’s alternative proposal. If she voted against the sale, it would be nine votes each way, giving the casting vote to the chair, Labour’s Rebecca Matthews.

Maybe the odds would shift further. Pannett had raised concerns the week before that councillor Tim Brown, the architect of the sale, had a “large shareholding” in Infratil, the majority shareholder of Wellington International Airport and a potential buyer of the council’s portion. Did he have a conflict of interest preventing him from voting? There were no Infratil shares disclosed in his declaration of pecuniary interests. On the eve of the vote, he declined to comment. It has since emerged that Brown remains the director of a company owned by Morrison & Co, which manages Infratil.

Brown wasn’t the only councillor with a potential conflict. Nicola Young owned over 20,000 Infratil shares through a trust. But council staff advised she was “extremely unlikely” to have a conflict as there was “no clear evidence that the value of any shares in Infratil would change as a result of a sale”. No councillors would be prevented from voting. It was back to nine votes each. Or was it?

The day of the vote came. Wi Neera addressed his colleagues. After lengthy deliberations, councillors raised their hand-held remotes, ready to transmit their votes. Was the privatisation of Wellington Airport about to be completed? Or had Wi Neera done enough to stop it?

For many of the councillors in the room, it had been a tortuous decision, as Wi Neera’s own change of position showed. But in recent days, the stakes had escalated further.

A week earlier, officials pulled councillors into a private briefing session, with media and the public excluded, and warned them of serious repercussions if they did not sell. The council budget would be left with a $450 million hole. Services would be cut. Rates would rise. The council’s credit rating could be downgraded. Councillors might even be replaced by commissioners – or even held personally legally liable.

It was both alarming and confusing. The public consultation documents for the long term plan said that not selling the airport shares would have “no impact on council rates or levels of service.” The advice was now totally different. Councillors were left shaken. What had been a difficult political trade-off now seemed to be no option at all.

Before Wi Neera got to his feet during the vote meeting, the mayor picked up the theme from council staff. The choice, she said, was about “the airport versus core services”. The council could sell the airport or “drastically cut back on public services to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.” These cuts “would be so deep the impacts would be felt in our communities for generations to come. It would mean less money for social housing, less money for libraries, pools, sports fields, less money for water, and better public transport and cycleways, or protecting our communities against the impacts of climate change.”

Now, the votes had been cast. The results appeared on the screen overhead. Ten votes for the sale, eight against. The airport was to be sold. Deputy mayor Laurie Foon, who had previously committed to opposing the sale, had flipped her vote. The reason: “new information that came to hand”. She believed selling the airport meant cuts to climate initiatives.

Whanau had done it. To get the sale over the line without the support of her left-wing colleagues, she built an ad hoc alliance with the council’s right. A series of last-minute amendments to the long-term plan spoke to the deals that had been done. Whanau promised to keep the Khandallah Pool open for another year, cancelled plans for paid parking in suburban centres, committed half a million dollars towards city safety initiatives, and diverted another half a million from Te Papa towards WellingtonNZ, the city’s economic development agency. “Those right-wingers got everything they wanted,” says Wi Neera. “The only thing that made them sad was we didn’t give them pick axes and send them out to tear up the cycleways themselves.”

For the Unions Wellington crew, who had watched the vote online, it was a devastating defeat. “It was awful,” says Ashok Jacob. “It was dawning on me what we were up against. This was the beginning of our finding out just how one-sided this process had been.”

They weren’t the only ones who felt something was wrong. Almost as soon as the vote was over, some councillors were crying foul.

The Order of the Rabbit

On April 10 1992, The Dominion revealed a decades-long conspiracy at the heart of Wellington City Council. Since the 1960s, a select group of senior officials had operated a secret society known as the “Order of the Rabbit”. Bound by arcane rituals and a shared hostility to elected councillors, members swore an oath to protect the interests of the order and keep its existence hidden. Members claimed it was all just fun and games – “a team building exercise” – but to mayor Sir James Belich, it had “more sinister implications”. Whatever the order’s true intentions, the scandal highlighted an often obscured part of the political process: the role of public servants in shaping political outcomes.

In theory, the job of public servants – whether in central government or at the council – is to advise elected representatives on their options and to implement their decisions. But it is no conspiracy theory to say that public servants may have interests of their own, and those interests can clash with the wishes of politicians. If it had not been for the influence of officials, Wellington Airport might not have been part-privatised in the first place. The origins of the neoliberal reforms that led to the 1998 airport sale are often traced to the influence of a small group of officials in Treasury and the Reserve Bank, whose manifesto-like advice to ministers ventured well beyond advising the government on how to achieve its goals and into the realm of ideology, directly challenging the underlying values of the welfare state. Fast-forward to 2024, and a group of councillors were worried that something similar was happening with the airport sale.

Labour’s Ben McNulty admits he wasn’t “up in arms” about the airport sale at first. He had previously worked in financial services and could understand the investment logic in diversifying the council’s assets. But there had been a “firm resolution” from the local Labour Party that councillors oppose the sale. When the council voted to put the airport sale out for consultation in November, it was McNulty who squared off against Wi Neera on Reddit to make the case for keeping the shares.

As the months passed, McNulty watched as the framing for the sale shifted from a general concern about “balance-sheet resilience” to fears that the council “might not have a budget that passes audit” if it didn’t sell. As the vote in May loomed, the intensity of official advice ratcheted up, culminating in the closed-door briefing one week before the vote, when officials laid out the grave consequences that could befall both the city and councillors personally if they did not sell.

McNulty received the advice “jaw open”. If this was the inevitable consequence of not selling, why had councillors not been advised of this until now? It felt to him like staff were “trying to put the fear of god into councillors”. And it worked, as evidenced by deputy mayor Laurie Foon’s last-minute change in position. But for McNulty, it had the opposite effect. He was now “radicalised” and saw the airport sale as “a conclusion searching for a justification”.

In the days following the May vote, McNulty, along with his Labour colleague Nureddin Abdurahman and Nīkau Wi Neera – dubbed “the airport three” – launched a public attack on the airport sale and the process that had brought them there. The Post’s Tom Hunt picked up the trail and, over the following weeks, published a series of stories that seemed to substantiate the trio’s suspicions.

Wellington City Council chief executive Barbara McKerrow said the “expert advice” the council had been relying on in the closed-door briefing was contained in two reports by consulting firm KPMG as well as advice from credit rating agency Standard & Poor’s (S&P). The KPMG reports had not been provided to councillors before the vote, but when they were released, 10 days later, they did not mention the $450m hole staff had warned of. In fact, the reports made it clear that keeping the shares would have no effect on rates, debt or levels of service.

The advice from S&P also wasn’t quite what it was made out to be, either. According to council staff, the agency had advised that the council’s credit rating would be downgraded if it didn’t sell, which could push up the cost of borrowing. But while the agency had expressed general concerns about the council’s finances, its advice mentioned the airport only once in passing.

Then, there was the advice that councillors could be personally legally liable if they didn’t sell the shares. In response to an information request from McNulty, officials advised they had received no “formal legal opinions” on this topic. McKerrow said the advice had stressed that the personal risk to councillors was “extremely tenuous”. As tenuous as it may be, McNulty says the advice felt like a “sort of threat… They put these serious legal threats on the table, but they’re not actually evidenced in a memo. They were just some off-the-radar comments in a public-excluded session.”

Attention soon turned to a new code of conduct McKerrow had introduced in 2023, which provided that officials wouldn’t supply information to councillors unless it related to upcoming decisions. The airport three called it an “information blockade”. A law professor called it “unlawful and unconstitutional”. Local government minister Simeon Brown soon chimed in, accusing McKerrow of “acting like a politician” and asking for an investigation. The issue was now about much more than just the airport — and it went well beyond Wellington. Across the country, councillors were questioning whether local government officials were wielding too much power at the expense of elected representatives. The decisions under scrutiny included the sale of shares in Auckland Airport.

As pressure mounted, McKerrow defended council staff, saying they had given “consistent” advice about the “serious financial resilience issues” the council faced. McNulty felt this was an “overtly heavy-handed approach” to make a sale “the one and only outcome”. Who was really in charge here? “The mayor is not leading us — the bureaucracy is leading us,” said Nureddin Abdurahman, a fellow member of the airport three. “The mayor didn’t campaign on the airport sale. She didn’t send a paper to KPMG to do the work on the sale of the airport. Who did? The bureaucracy did.”

Not all councillors agreed. Geordie Rogers told his colleagues he didn’t “believe there is a cabal amongst the staff who are out to undermine our process”. Tamatha Paul also spoke highly of staff from her time on the council. “I think the council does a pretty earnest job of giving us the information we need,” she says.

But to Abdurahman, what was going on wasn’t some conspiracy. “In any governance environment, if your governance is weaker than the bureaucracy, the bureaucracy will get involved in the governance. The bureaucracy will govern you. … They are human like us. They have values. If they get a way, that is what they will do.”

In the eyes of the airport three, all this drama had a point. It showed that the decision to sell the airport was flawed. With the council scheduled to meet on 27 June to vote on the long term plan as a whole, they saw their chance to revisit it. However, to stop the sale, they would need the support of their Labour and Green colleagues. They weren’t sure they had it. Comrades were fast turning into enemies.

‘Burn the house down’

From the moment it was first proposed in November 2023, Nureddin Abdurahman, the soft-spoken Labour councillor from south Wellington, promised to fight the airport sale until the end. It would have been naive to doubt him. This was the former taxi driver who had once taken Uber to court in a landmark employment law case. Abdurahman had no intention of giving up now. “It was a promise that I had given to the community. I promised I would not sell their strategic assets,” he said.

Within weeks, the ad hoc alliance the mayor had forged to get the sale over the line in May fell apart, as right-wing councillors Diane Calvert and Tony Randle switched sides when they learnt the council’s $272 million debt headroom would not be retained if the airport was sold. Or so they had been led to believe. A majority of councillors now opposed the airport sale. The sale surely could not go ahead. But not all the councillors on the left felt so sure. To some, the issue had already been decided, and it was now time to move on.

For their part, the Greens were navigating a conundrum: a Green mayor and deputy had voted to sell the airport despite signing an election promise that they wouldn’t sell the airport. Party officials sought to frame the issue to local members as a “conscience/split” vote. Wi Neera’s attempt to get the parliamentary Green caucus involved had been poorly received by his council colleagues, but they had “worked it all out”, he said. Tensions across the broader left bloc, however, were anything but settled.

The airport three declared they had lost confidence in the mayor and would no longer vote with her unless she provided “guarantees” around other progressive issues. Abdurahman escalated things further, issuing an ultimatum on the airport sale. If he had to, he would lobby councillors to vote down the entire long-term plan at the end of June – a drastic move which would leave the council without a budget. The council had two options to avoid this, he said. It could vote on selling the shares again. Or it could have two long-term plans audited – one with the share sale and one without.

Abdurahman’s Labour colleagues Rebecca Matthews and Teri O’Neill were not pleased. O’Neill called Abdurahman’s moves a “political stunt” that would push the council’s books into “dangerous territory”, potentially prompting the government to intervene. “I agree that selling the airport shares wasn’t a good decision, but we’ve still got to come in to work and do our jobs”, she said. Matthews posted a barely-coded tweet criticising the airport three. “For me, progressivism in local government is using my vote and voice according to my values, working in teams to get good stuff done, not centring myself in every situation, taking a win or loss with good grace, supporting others to lead and not punching down. I think it’s working out OK.” Both Matthews and O’Neill planned to vote for the long term plan, even if it included the airport sale.

Behind the scenes, the vibe was toxic. Colleagues of the airport three and council staff were briefing reporters anonymously that the trio’s actions were ego-driven, bewildering, and even “misogyny”. Wi Neera was incensed, “They’re trying to paint us as wreckers and egotistical and sexists and trying to hold the council hostage. But we’re the only ones actually sticking up for left values. I kept an election promise; you guys broke it.”. McNulty stopped attending meetings of the Labour-Green caucus. Abdurahman said he understood the risks of his high-stakes gambit and was “happy losing a job for standing up for the right thing.”

Ultimately, Abdurahman didn’t want to torpedo the long term plan. What he wanted was a separate vote on the airport. The question was how – a question that Abdurahman felt should have a simple answer. But it didn’t. Throughout June, attempts to set up a separate vote ran into a tangle of legal impediments – the council’s standing orders, its delegations to its committees, and the Local Government Act. Abdurahman was frustrated. The advice from officials on these procedures seemed to him to only “favour those who want to sell the airport”. He attempted to secure a separate airport vote right up until the last minute, but it was no use. The long term plan passed, airport sale included.

In ordinary circumstances, that would have been the end of it. But these were not ordinary circumstances. The council had locked in its 10-year plan, but a majority of councillors opposed a core part of that plan. Abdurahman, speaking on the day of the vote, put it this way: the long-term plan was “undemocratic, crappy, sugar-coated poison”.

When it was all over, Abdurahmann would say he was lucky to have been through all this and to have his values tested in the face of pressure. But that was a while away. The worst was yet to come.

In the third and final instalment of Privatisation Lost, out tomorrow: The unionists, the airport three and mana whenua come to a head before the final vote. And is winning always better than losing?