Te Tiriti isn’t about affirmative action. It’s about power.

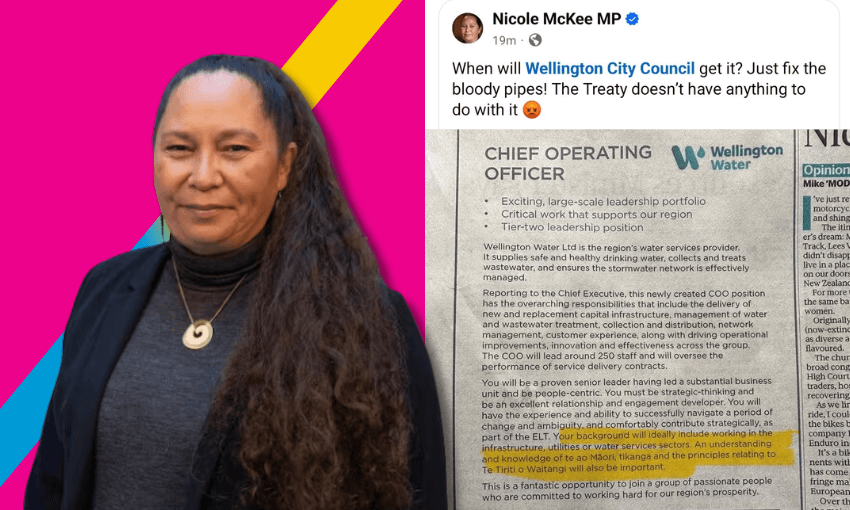

In a recent Facebook post, Act minister Nicole McKee lambasted Wellington Water for a chief operating officer job listing which required applicants to have knowledge and understanding of te Tiriti o Waitangi. “Just fix the bloody pipes! The treaty doesn’t have anything to do with it,” she wrote.

But te Tiriti isn’t just a buzzword in this instance, it’s directly relevant to how Wellington Water is governed. The Crown’s Treaty settlements officially recognise Ngāti Toa and Taranaki Whanui as having rights and decision-making powers over water. The chief operating officer of Wellington Water has to manage the competing interests of iwi and Crown. It’s te Tiriti in practice.

McKee’s frustration isn’t entirely unfounded. Demonstrating knowledge of Treaty principles has indeed become a box-ticking exercise for many public service jobs. She is lumping te Tiriti into the wider culture war alongside DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion), corporate diversity pledges, wokeness, and other things that make her voters mad.

Her party leader David Seymour often uses a similar framing, tying Te Tiriti to affirmative action policies. In his select committee submission on the Treaty principles bill, he spoke about health providers prioritising Māori and concert organisers who charged higher ticket prices for non-Māori. He described te Tiriti as an agreement between two races and emphasised perceived racial inequalities.

It’s no surprise that Act has pursued this line of argument. Concerns about affirmative action and other diversity policies are real and growing, in New Zealand and abroad. But it’s not really about te Tiriti. A government could change its approach to affirmative action policies without needing to rewrite the nation’s founding document.

Te Tiriti isn’t an agreement between races. It isn’t a diversity pledge, an anti-racism initiative or a promise to favour Māori individuals. Te Tiriti is a power-sharing agreement. It’s a deal between two sovereign entities setting the foundations and limits of a new government.

The text of te Tiriti recognises and protects two forms of power in New Zealand: kawanatanga, the powers of a governor, and rangatiratanga, the powers of a chief.

Having two sources of power isn’t inherently strange. Many countries have multiple layers of local, state and federal government, upper and lower houses, and a separate judiciary.

In New Zealand, by comparison, power is incredibly centralised. Parliament has absolute legal supremacy. It has assumed the decision-making power of the kawana and turned the governor-general into a mere figurehead. New Zealand’s supreme court cannot overrule laws passed by parliament. There is no upper house to limit its power. Parliament abolished provincial governments and eliminated the legislative chamber.

A New Zealand government that maintains the support of the parliament has theoretically limitless power. Justice Robin Cooke once argued that there was some line the courts would not allow parliament to cross, but that has never been truly tested. The only limit on power is the election every three years.

There are some advantages to this system. Governments can respond quickly and decisively to new threats – from the economic reforms of the 1980s to the Covid-19 lockdowns. But because parliament has absolute power, it is bound by nothing – not even te Tiriti o Waitangi. Parliament could, in theory, breach te Tiriti in any way it wanted. It could cancel all Treaty settlement claims. It could pass a law declaring te Tiriti “a simple nullity”.

This National/Act/New Zealand First coalition has been defined by its attempts to consolidate power. The fast-track bill takes power from the courts and puts it in the hands of ministers. Its local government reforms have limited the decision-making powers of local councils. And the Treaty principles bill is a constitutional power grab – it restricts the interpretation of tino rangatiratanga and concentrate more power in the Beehive.

Some may ask what’s the problem with that? Parliament is elected by the people, it’s a democratic institution. If the majority of people want to eliminate the powers of iwi, why shouldn’t they? But that’s exactly what the Tiriti was intended to prevent. It is a guard against a future authoritarian leader or the tyranny of the majority.

When he proposed te Tiriti, William Hobson said he would protect Māori customs and religion. He made specific promises about what the government would and wouldn’t do – it wasn’t just his word, but the word of the Crown.

In April 1840, while te Tiriti was still travelling around the motu, Hobson wrote a letter to chiefs who were worried their lands, customs and status would be trampled on and degraded. To reassure them, Hobson made a pledge, which would make a good oath of office:

“The Governor will ever strive to assure unto you the customs and all the possessions belonging to the Māori. The Governor will also do his utmost towards the maintenance of peace and goodwill and industry in this country.”

Hobson promised the government would always protect the power and status of iwi.

David Seymour says we need a national debate about te Tiriti. And he’s right, we do. But it shouldn’t be discussions about affirmative action. It should be about whether our current system of parliamentary supremacy makes sense in a country centred on te Tiriti, which inherently acknowledges that the governor does not have supreme power.

What would New Zealand’s system of government look like if it was designed to honour te Tiriti? It could mean giving the governor-general the power to refuse royal consent on laws that breach te Tiriti. It could mean giving the Supreme Court the power to overrule parliament on Treaty matters. It could mean a second house of parliament, made up of iwi representatives, with the ability to challenge or veto legislation. It could mean, as Te Pāti Māori has suggested, a parliamentary commissioner to assess legislation violating te Tiriti.

Whatever it may be, stronger legal protection will help to uphold the mana of te Tiriti, so that a future parliament can’t unilaterally decide to abandon William Hobson’s pledge.