Most pets in New Zealand are of the furry, four-legged variety. But other species can make just as rewarding companions, Naomii Seah discovers.

“Watch, they’ll all come up,” says David Willcox. He’s carrying a massive bucket of beige animal pellets, and with one motion, he scatters a scoopful of feed over the murky water in front of us. Slowly, bright orange, red and white spots appear underneath the surface of the pond. Then, the points of colour suddenly become a carpet of patterns. Hundreds of goldfish surface, gulping at the feed on the skin of the water. They move sluggishly due to the warm weather, creating a mesmerising pattern of golden ripples that sparkle even on an overcast day.

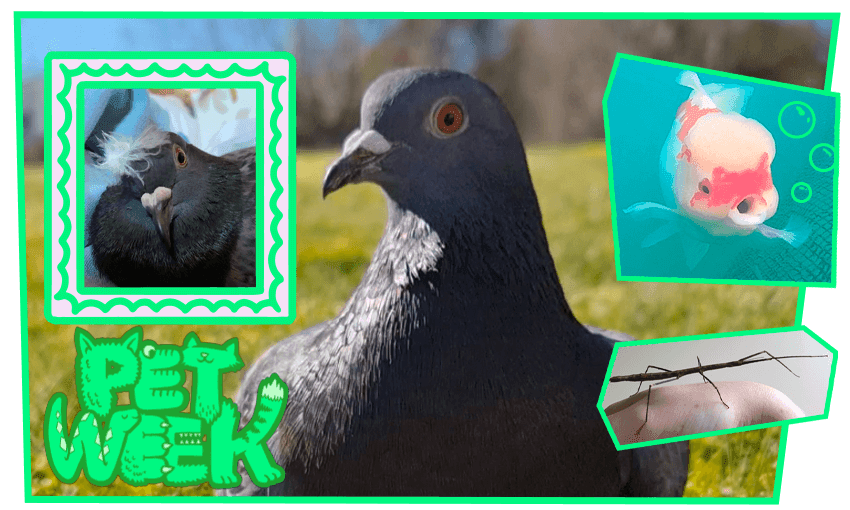

I’m on the trail of New Zealanders who raise “strange” pets, because as self-described “Pigeon Lady” Lauren Hayes Jordaan points out, there seems to be “a perception that cats and dogs are the only pets”, especially in urban areas. But there’s a section of urban New Zealand pet owners that show just as much dedication to their winged, scaled and antennaed friends as many of us have for our fluffballs.

Warkworth-based David Willcox is a goldfish breeder, but he considers himself an unabashed fan of all fish. When I visit he’s wearing a black t-shirt with the image of an angler screen-printed in white, and a smoothly carved necklace in the shape of a goldfish that he later tells me he made himself.

Willcox has kept fish for 22 years, and been in the goldfish breeding game for 16 of those. “He started with saltwater fish, and his first tank included leatherfish, pufferfish and frog fish, as well as corals, anemones and other species that others wouldn’t normally consider “pets”. When I ask about his favourite fish, Willcox begins to reminisce about Rambo, the dragon wrasse. “He was really smart,” says Willcox, describing the sandcastle houses that Rambo would build every day, stacking rocks and sand meticulously before diving into them at night. “[Fish] all have different personalities,” he says.

In addition to the ponds, Willcox also has a breeding area with many more large goldfish waiting for mating season. He’s passionate about goldfish breeding, and tells me he’s considering going back to study for a degree in genetics. He talks about the colour varieties he wants to produce in future, noting that cross-breeding certain colours and patterns should get him to a fish that more closely resembles koi carp. But the exact method? “That’s a secret,” he winks.

That’s because competition is high in the industry, and his clients are mostly looking for fish that resemble the invasive koi species, which have been banned as they’re fouling our waterways. But given proper care and a big enough pond, Willcox says there’s no reason goldfish can’t grow to a similar size and look just as beautiful. During my visit, I saw the largest goldfish I’d ever seen – my estimate put it at approximately 30 cm from head to tail. “That’s not even their full size,” chuckles Willcox. The fish I saw was about the size of a small koi carp; in captivity, most koi grow to around 60 cm.

Willcox doesn’t sell to just anyone, though, especially not to those he thinks will mistreat their fish. “I turn people away sometimes. It’s hard because it’s all money, but I’ll say no, I don’t want to sell you my fish actually.”

At the other end of the country, in Dunedin, Lauren Hayes Jordaan unexpectedly found herself with a lifelong pigeon companion when she volunteered to help the local Bird Rescue. They gave her a baby homing pigeon to look after, and Jordaan wound up being the pigeon’s “person for life”.

“I didn’t really plan on keeping her,” says Jordaan. “I thought she’d leave so I just called her Pidgey… but she never left, [so] I tell everyone I named her after the Pokémon.”

Jordaan says Pidgey is a very needy pet, and will get anxious if she leaves for too long, or if there’s strangers around. She chalks up this need for attention to pigeons being quite flock orientated. But there are plenty of positives to owning a pet pigeon. Besides the cuddle time, Pidgey is quite handy to have in the kitchen. “She’ll clean up any little snacks on the floor,” Jordaan laughs.

But she doesn’t recommend others go and get a pigeon for themselves. “I’m a conservationist, so I don’t think people should be keeping pests as pets. It’s different if you’re rescuing one, [but] they will always prefer the natural habitat and being with the flock of other birds.” Jordaan says she’s giving Pidgey the best life she can have as she’s a rescue, but she doesn’t want others to start grabbing baby pigeons out of nests.

While pigeons aren’t classified as a pest species as they cause little issue on their own, anyone who lives near a flock knows “they can definitely get quite high in numbers,” Jordaan says.

“Ethically and morally, every animal has the right to be rehabilitated and have the opportunity of life. Even pests – it’s not their fault that they’re here. I would rescue any animal any day.” When it comes to choosing a pet, Jordaan urges people to give it plenty of thought. “Don’t just pick any animal; think about where you live, think about the environment you’re in, think about the behaviour of the animal you’re bringing in. What can you provide for it? And ultimately, would it be happier with you? Or would it be happier where it was?”

Auckland biologist Lucy Kelly shares this sentiment. She says she didn’t seek out her particular invertebrate companions, but ended up rescuing a number of stick insects over a few years, including one with only five legs that her friend found in the middle of the road. Her most recent stick insect companions, Steve and Leggy, were retired experiment subjects that Kelly’s close friend had collected for their master’s degree. She describes stick insects as “some of the coolest pets I’ve ever had,” but echoes Jordaan’s warning that people shouldn’t seek them out as pets.

All stick insects in New Zealand are native species, though they aren’t protected under the Wildlife Act 1953. Kelly describes the legislature as having “massive gaps” for certain classes of wildlife, such as insects and other invertebrates. But although collecting stick insects doesn’t require a permit as with some other wildlife, Kelly warns against collecting them “unless you know what you’re doing”.

“Stick insects aren’t doing very well, nationally,” she says. “We just don’t know that much about them. They’re very difficult to study, and things like invasive wasps, invasive birds [and] insecticides have really decimated their populations.”

Additionally, stick insects are really hard to care for in captivity, says Kelly. It’s more labour intensive than you might think too – she regularly gathers branches of fresh foliage, mostly mānuka and kānuka, for her stick insects. If you’re inexperienced, transporting plant material could also pose a risk to our natural environment by inadvertently spreading plant disease like myrtle rust. Stick insects also require a high level of humidity to periodically shed their skin. Kelly would mist hers every so often. But even this is a delicate operation, as keeping the enclosure too wet could lead to fungal disease.

But although finicky to care for, stick insects only live for about a year, and their adult form – the ones you’re most likely to spot, and the sort that Kelly was gifted from her friend – represent the end stages of their life. Kelly was looking forward to retiring her stick insect terrarium when the unexpected happened: her insects promptly began a weeks-long stick insect “orgy”, laying eggs before passing on. She didn’t bother to clean out the enclosure as she was told stick insects were difficult to hatch, but that advice would be proven wrong. Soon Kelly was dealing with hundreds of baby insects. The mesh over the terrarium was designed to stop the adults escaping, but it was too large to contain the minuscule baby insects; Kelly describes an afternoon of gently scraping newborn stick insects off the roof and walls around the enclosure. It was too cold to release them outside, so Kelly raised them, and began rehoming them with other biologist friends once they got too big.

Stick insects, like Wilcox’s fish, are another animal that have a surprising amount of personality once you get to know them. Kelly tells me about the biggest baby stick insect, Twiggy, who loved to dance. “She’d stick her front legs out and go back and forth,” said Kelly. Another insect, Stumpy, didn’t like Kelly much at all.

When the weather got warm enough for them to survive in the wild, Kelly organised a massive release into the Auckland Botanic Gardens. She said the experience was rewarding, as an unintended “hatch and release [conservation] effort,” but she doesn’t plan on raising more stick insects in the future due to conservation concerns.

“I think it’d be really cool for people to be able to interact with them. You know, hang out with them and see them, and maybe one day, we’ll be able to reach a point where everyone can have their own stick insect.”

But for now, Kelly recommends those looking to interact with stick insects to go out with a torch at dusk in the summertime and observe them. Totara Park is a good place to start if you’re in Tāmaki Makaurau. To spot them, Kelly recommends looking at native trees, as most species feed off native flora. For those looking to “keep” stick insects, you can make your garden or home a welcoming place for them by implementing pest control, planting native species, stopping the use of insecticides, and otherwise encouraging biodiversity.

As with other pets like cats or dogs, owning any type of animal comes with its own unique set of responsibilities and considerations. Imogen Bassett of Auckland Council notes that “almost all pets in Aotearoa are introduced species that have the potential to harm our native wildlife”. She cautions that any non-native species should never be released into the wild.