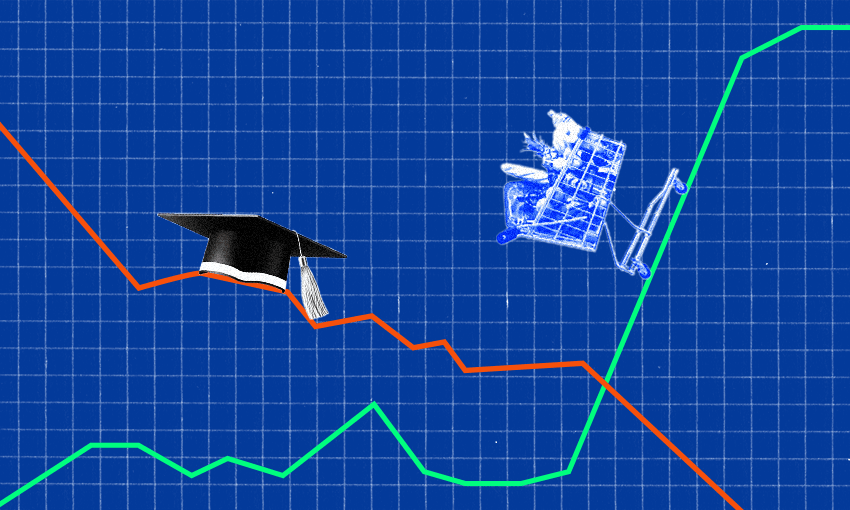

While your grocery bills suggest otherwise, high inflation is not all bad news – especially if you’ve got a New Zealand student loan, Emma Vitz explains.

High inflation sucks. The price of lettuce appears to be doubling every time you go to the supermarket. People who bought into the property market during the sugar rush of 2020 and 2021 are now feeling the crash as interest rates bite. Adrian Orr is the new, much less reassuring Ashley Bloomfield of our time.

Hidden among the high prices, however, is a small win for many New Zealanders that most of us aren’t even aware of. That win? Your student loans are being worn away by inflation.

In New Zealand, we don’t apply indexation (adjustments to account for inflation) to student loans. This means that if you took out $10,000 of student loans in 2000, they would still cost you $10,000 to repay today, even though hourly wages have doubled since then. That’s inflation eroding the value of your student loan, and it makes it faster to pay off.

New Zealand’s approach to student loans is fairly unusual. In Australia, indexation is applied to student loans once a year to maintain the real value of the debt that is owed to the government. Because inflation is so high right now, the indexation rate this year is 7.1%, which has many people panicking.

In the UK, student loans are charged an interest rate of the retail price index (RPI – a measure of inflation) plus up to an extra 3%, depending on how much you earn. In response to RPI being as high as 14.2% in the past year, interest rates on student loans have been capped at 6.9%.

So how much time and money is our unique approach saving borrowers in New Zealand?

According to the latest student loan scheme annual report, students who graduated in 2020 with a bachelor’s or graduate certificate/diploma had a median student loan balance of $35,940 at graduation. The median repayment time for these borrowers is projected to be 7.3 years. The median student loan balance was slightly higher for male students, but they are projected to pay it off a bit faster.

Using this information along with data on salaries for graduates, we can reverse engineer a payment trajectory that aligns with the overall results from the (much more sophisticated) model produced by the Ministry of Education using data from the IDI. We can then apply indexation to this to see how it would affect pay-off times.

I used the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to index the student loan balance on March 31 each year, to match the point in time where repayment thresholds (the amount of income you can earn before the 12% repayment rate kicks in) are currently adjusted. It would make more sense to use a measure of wage inflation to index student loans, since that is what is really eroding their value. However, other countries use CPI or something similar, so I decided to follow suit.

The results show that applying indexation would mean the average student took an extra year and a bit to pay off their student loan, and paid about $7,250 extra.

You can see that things would really heat up for a recent graduate in 2022 and 2023, when inflation spikes. Along with recent historical data, I used the RBNZ projections from the Monetary Policy Statement of May 2023 for future inflation. They forecast that inflation has peaked and will return to 2% in September 2025, which is why the loan balance increases by much less in the future. Of course, all of this is uncertain.

While the fact that the real value of student loans is being eroded faster due to high levels of inflation is a small win for borrowers, it also means that as the lender, the government is losing more money on the student loan scheme.

According to the Ministry of Education, in 2020/21, every dollar lent out as a student loan cost the government 32.75c. In 2021/22, this increased to 37.79c, reflecting the fact that the government is losing more money by not accounting for interest in a high-interest environment. The value of the student loan scheme to the government as a whole dropped by $1.67 billion between FY2021 and FY2022 because of changes in inflation and interest rates.

Recent graduates are being squeezed by a high cost of living, while simultaneously facing a labour market that might finally be slowing down. Whether or not you believe student loans should be indexed, those on the borrowing end of this equation will be glad that New Zealand is doing things differently.