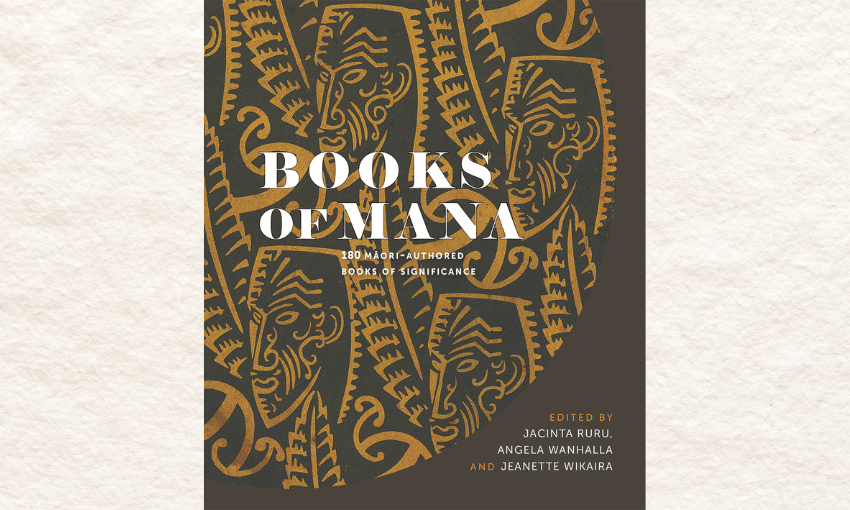

Books of Mana: 180 Māori-Authored Books of Significance, edited by Jacinta Ruru, Angela Wanhalla and Jeanette Wikaira has just been released by Otago University Press. In this essay, Books are Taonga, Jeanette Wikaira explores her personal relationship to books and their value.

For me, books are taonga. The knowledge they contain, the feel of them in my hands, the smell of the paper, the beauty of the object, the story of the author and the excitement of being transported somewhere new or the curiosity of learning something new are all important to how I experience a book. Books and taonga are two things that have loomed large in my life. Let me explain.

We didn’t have much growing up, but we had books. We also had a love of reading, learning and knowing something about the world beyond our community. My parents instilled in my brothers and myself a belief that education was the means to lift ourselves into a better future, and access to books was part of how they intended us to succeed. In my whānau there wasn’t much money for extras, but there was money for books. They were not grand books – we had comics, novels, encyclopedias: humble books that were passed between siblings. I was the youngest, so the books stopped and stayed with me.

As kids we read whatever came into the house – everything from Tolkien to Te Ao Hou periodicals, the Bible in te reo Māori, Best Bets, rugby almanacs, trashy novels, classic novels and my father’s whakapapa papers.

Both my parents were raised in small Māori communities on the Coromandel Peninsula and both had left school by the age of 16. My father grew up in the small settlement of Manaia and my mother was raised by her grandmother in the Waiomū valley, along the Thames Coast. Both were surrounded by extended whānau, where their connection to their whenua, awa, moana and maunga was central to their lives. Theirs was a life vital and alive in Māori knowledge systems and ways of being and thinking, even if they did not realise it at the time. So despite my parents not being formally educated in a Western sense, in our whānau, as in so many other Māori whānau, knowledge and learning are deeply entrenched and respected and books are revered.

My story with taonga begins in 1984, when I was 14 years old. Te Karere was still new to television and as a family we often sat and watched this wonderous advancement of te reo on the television. One day the Māori news coverage showed images of a barricaded Fifth Avenue in New York and a stream of yellow cabs halted outside an imposing and majestic building. On the steps of this building a group of Māori were gathered – kaumātua and rangatahi, waiting in the half light of dawn for the first words of ritual. The scene was electric and bristling with spiritual energy. I couldn’t comprehend that a Māori ritual scene so familiar to me was happening in such a foreign place. Witnessing the 1984 opening of the Te Maori exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York on television was my first introduction to the power of taonga. I was transfixed. It was both unsettling and profoundly moving to see our taonga come alive in the halls of such a physically imposing building so far from Aotearoa.

Two years later, in 1986, I saw the exhibition in person when it returned to Aotearoa. The emotions I experienced viewing Te Maori as a 16-year-old were so confronting that they have stayed with me over my lifetime, and eventually led me to work in the cultural heritage field. Encountering taonga of exquisite beauty within the confines of a museum was and often continues to be breathtaking and awe-inspiring, an experience of cultural pride mixed with confusion, loss, pain, grief and overwhelming wairua.

Spiritual and material taonga

Taonga have always been used as vehicles to channel knowledge, ideas and ancestral connections. Acting as a mnemonic to memory, when activated with cultural practice, taonga are crucial conduits for past knowledge to pass to current generations and into the future.

Taonga is a broad and encompassing word. In the Māori version of Te Tiriti o Waitangi the Crown granted te iwi Māori tino rangatiratanga over our whenua, kainga and taonga. Taonga, in this sense, includes everything that is important and has been handed down to us by our ancestors.

Te reo Māori is a taonga: ensuring te reo is taught in schools, Māori voices are encouraged in society and Māori ideologies flourish are ways we continue to activate and practise this taonga.

Mauri ora is a taonga: taking a holistic approach to the health of our people that utilises not just Western medicine but ancient Māori approaches of rongoa and oranga are ways in which we ensure this taonga can flourish.

Te ao tūroa is a taonga: making sure we work hard to clean our waterways and look after the native ngahere and creatures of this land, with whom we have a symbiotic relationship, are ways we protect this taonga.

When understood in this way, taonga represent myriad ancestral connections that reinforce te ao Māori.

Taonga are also material cultural artefacts. Material taonga have always performed a core function within the Māori world, marking important ancestral figures and key ancestral historical moments. Through art practices of whakairo, raranga and tā moko a sophisticated artistic language developed that enabled the transfer of oral knowledge systems within a material form that we know as taonga. Taonga, together with the oral tradition, are valid and robust primary sources in te ao Māori. When taonga are activated through cultural practices such as kōrero, pūrākau, whaikōrero, karakia and waiata, they become vessels that enable a constant weaving and reweaving of relationships between past, present and future, opening up pathways to other ways of knowing and understanding.

Symbols as taonga

Te ao Māori expressions of Māori knowledge relate to a complementary world of symbol. Symbols are deliberate human creations used to depict perceived reality: concepts, formulae, forms, ritualistic ceremonies, interpreted stories, maps, models and paradigms. These forms are visualised within the mind and manifested as material objects or taonga as a way of understanding the world behind space and time.

In the early period of Māori interaction with Pākehā, Māori rangatira sketched their moko on paper, utilising them as legal signatures for land transactions and as self-portraits. The moko at the time was the primary marker of Māori identity. Art historian Ngarino Ellis argues that these moko signatures and drawings are sites of intersection between Pākehā print literacy and Māori oral literacy. Like taonga, these moko drawings act as mnemonic devices in that they have the capacity to reveal the wider worlds in which our ancestors engaged, not only culturally, but also artistically and politically. Rangatira who signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi did so using symbols, many with marks representing their moko. Such marks are regarded by Māori as tohu ‘signs’ – not only physical markings on paper, but also visionary signs of the future.

Image as taonga

Painted and photographic portraits do two important things: they record likenesses and bring ancestral presence into the world of the living. Māori images of ancestors are not merely representations, they are considered to be an embodiment of those ancestors. These are taonga, to be treated with great care and reverence. In te ao Māori, after a person has died, their portrait may be hung on the walls of family homes and in the wharenui, to be spoken to, wept over, and cherished by people with genealogical connections to them. Even when Māori photographs and painted portraits are held in institutional collections and are absent from their whānau, the stories woven around them keep them alive and present. Many cultural heritage institutions, galleries and museums acknowledge these living links through enduring relationships with descendants of those whose painted portraits and photographs are held and cared for within institutional collections.

Bridget Reweti’s 2021 exhibition Pōkai Whenua, Pōkai Moana at the Hocken Gallery in Dunedin retraced the journey of ancestor Tamatea Pōkai Whenua Pōkai Moana, who arrived in Aotearoa on the Takitimu waka and travelled from Tauranga Moana in the north to Murihiku in the south. One aspect of the exhibition explores a contemporary Indigenous understanding of the concept of tapatapa whenua, of sighting and naming landscape. Through landscape photographs from 1889 (taken by Alfred Burton of the famed Burton Brothers) Reweti reclaims and re-records Burton’s original views with a consciousness of the silence of Indigneous existence and knowledge in the original Burton photographs. Reweti’s reframing of the Burton Brothers’ landscape photographs is a contemporary example of how Māori artists are claiming image as taonga.

Writing as taonga

Books combine paper, image, symbol and the material dimensions of taonga with words. The impact of the introduction of written material for Māori was profound. During the early period of Māori and Pākehā interaction, when print culture was first introduced, books and literacy carried a power and a value that Māori ancestors took up with enthusiasm. Tīmoti Kāretu writes that the introduction of literacy into the Māori world was both liberating and limiting.2 It was liberating in the sense that Māori no longer needed to commit large volumes of whakapapa and tribal histories to memory. For the first time, literacy allowed important kōrero to be committed to paper and referred to when necessary.

However, literacy also proved limiting, because once an oral whakapapa or tribal kōrero was committed to text, it tended to become the version, and errors captured in print were often perpetuated in use.

Māori ancestors wrote to express their anger at the loss of Māori land; they wrote to share their views of the politics of the day; and they were prolific writers of letters to each other, to newspapers and to colonial officials. These early writings are taonga because they tell the story of Māori mastering the art of literacy and using this new technology to become keen writers. Māori writers developed a writing convention based largely on the protocol of marae whaikōrero complete with waiata written to bring their writing to a close.

Libraries, archives and cultural heritage institutions have often grappled with this notion of books as taonga. While “traditional” material cultural artefacts are readily understood to be taonga, the acceptance that books, archives, photographs and paintings are also taonga in their own right has been a slower transition for many curators and institutions to make because it requires an understanding of the nature of taonga and their cultural connections that reinforce and activate te ao Māori.

Books as taonga

A book is a physical object, yet it also signifies something abstract, in the sense of the meaning conveyed by the words. Thus, I believe, a book can be seen as more than its contents alone. A book is a metonym for the words that we read, for the thoughts and ideas we have as we read it and the knowledge that is transmitted from author to reader. Māori-authored books, such as those featured in the Te Takarangi collection, have further value, containing the presence of many others from the past and important knowledge that may be lost to the current generation. The book becomes a vessel that embodies the mana of the author, the presence of others and the knowledge contained within.

Additionally, Māori-authored books are intricately connected to our history and experience as Indigenous people of this land. They have further significance for a people whose language and knowledge have been disrupted through the processes of colonisation. Books as taonga hold the power to affirm Māori identity and interrupt power struggles by the profoundly simple cultural practice of pūrākau, storytelling through the written form. In this sense the books in the Te Takarangi collection do something taonga never needed to do: they retell our stories from the brink of colonial loss; they reclaim Māori identity, culture and knowledge; and they remind us and future generations that mātauranga Māori continues to be vital.

The particular reverence that many Māori whānau, like mine, have for Māori books as taonga is linked to books possessing a life beyond the physical. For books can possess a life of their own. In my whānau, our love of books, nowadays scholarly books written by Māori, is a powerful thread woven through the generations. For my grandparents’ and parents’ generation, their taonga were whakapapa books, treasured tribal histories, and new stories found within the pages of the Te Ao Hou journals from the new urban Māori world. These were their opportunity to reclaim knowledge lost.

For me, I have found my taonga in the expansion of mātauranga Māori across the arts, philosophy and the historical and political work of Māori scholars. Te Takarangi’s body of published taonga is broad, thoughtful, culturally rich and mind-expanding.

Books of Mana: 180 Māori-Authored Books of Significance, edited by by Jacinta Ruru, Angela Wanhalla and Jeanette Wikaira (Otago University Press, $65) is available to purchase from Unity Books.