With the repeal of Section 7AA of the Oranga Tamariki Act looking set to go ahead, with some key changes, here’s what we can learn from North America.

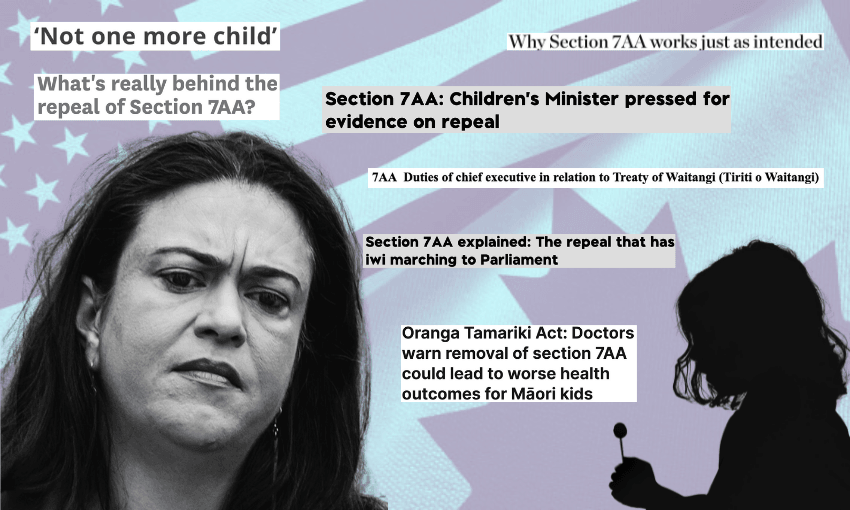

The Oranga Tamariki (Removal of Section 7AA) Amendment Bill recently had its second reading in parliament. The bill would repeal section 7AA of the Oranga Tamariki Act, a provision intended to uphold te Tiriti o Waitangi within our child protection system. The proposed removal comes despite widespread opposition from Māori and a 2024 Waitangi Tribunal report that found it would breach the principles of te Tiriti and harm Māori children and families. The report was scathing, with the tribunal concluding that “we are struggling to understand how any government having proper regard to the Treaty could conclude that the repeal of section 7AA was appropriate.”

Despite the above, the repeal of section 7AA looks set to continue. The government’s determination to move forward is hard to fathom, given the widespread evidence – including from Oranga Tamariki officials – that section 7AA has helped to improve outcomes for children. There is no evidence that the repeal will make Oranga Tamariki more efficient or effective. In light of the broad range of anti-Tiriti measures being championed by this government, it is difficult to see the repeal as anything but yet another attack on Māori.

However, last month’s second reading of the bill featured one notable change. Part of section 7AA compels Oranga Tamariki to consider forming “strategic partnerships” with iwi and Māori organisations. Ten such partnerships have already been formed, and these so-called “strategic partners” were some of the most vocal opponents of the repeal during the select committee process. Perhaps as a result, the revised version of the bill retains these partnerships, continuing to repeal section 7AA but incorporating the partnerships aspect of it elsewhere in the legislation. Will that dampen the opposition to the repeal? More importantly, will it actually uphold te Tiriti o Waitangi and improve things for tamariki and whānau Māori?

One source of answers to these questions may lie overseas. A recent research project, supported by Ngā Pae o te Maramatanga, has examined the issue of Indigenous child protection in Canada and the United States. Specifically, the project sought to understand the ways in which the legal and policy frameworks for child protection in those countries uphold the rights of Indigenous peoples, and how those frameworks differ from Aotearoa New Zealand. The project found that although the laws and policies of those countries are far from perfect, in some ways they are well ahead of us. In particular, there is a recognition that the care and protection of Indigenous children and families is first and foremost an issue of Indigenous sovereignty.

That is a major difference from the approach taken here in Aotearoa New Zealand, where the term “rangatiratanga” does not appear in the Oranga Tamariki Act. This is a significant shortcoming of that law, because tino rangatiratanga is arguably the most central aspect of te Tiriti o Waitangi. The term rangatiratanga has been variously translated as authority, independence or self-determination, with the intensifier “tino” in this context simply meaning “complete” or “absolute”.

So while reference to te Tiriti o Waitangi was finally added to the Oranga Tamariki Act for the first time in 2017, the lack of reference to rangatiratanga (let alone tino rangatiratanga) means those provisions still fall well short of fully upholding te Tiriti. An earlier Waitangi Tribunal report, published in 2021, found the failure of the law to acknowledge rangatiratanga amounted to a “fundamental and pervasive breach of te Tiriti/the Treaty and its principles”.

In contrast, the legal frameworks for Indigenous child protection in Canada and the US both start from a recognition of Indigenous sovereignty. This has been the case for almost 50 years in the US, with the passing of a law called the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) in 1978 being a key milestone. Developments in Canada are more recent and arguably more comprehensive, most notably in the form of a 2019 law called Bill-C92: An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children.

Both Bill C-92 and the ICWA affirm Indigenous peoples’ rights to raise their children according to their own laws, traditions and customs, framing child protection as an issue of Indigenous sovereignty. They establish that any government intervention in Indigenous families must be guided by this fundamental principle. Recently challenged in the Canadian and US Supreme Courts, both laws were upheld as constitutional, confirming their alignment with the broader legal frameworks of each country, including human rights protections. In effect, the highest courts in North America have decisively recognised Indigenous jurisdiction over child welfare, signalling a growing legal consensus that treating Indigenous child protection as a sovereignty matter is largely uncontroversial.

Despite Aotearoa not being identical to the US or Canada, we can learn from these examples. The development of iwi social services and other kaupapa Māori organisations over the past 40 years has left Māori communities better placed to resume control over our own child protection systems. Such organisations are part of what academic Kathie Irwin has termed “the Māori cultural infrastructure”, and are a key reason why now is the time for change. As Moana Eruera, chief executive of Ngāpuhi Iwi Social Services, said during the hearings into the repeal, “we have obligations to our people, and want accountability and responsibility for providing those solutions. We have them, we work on those solutions every day.”

In many respects, these developments on the ground mirror what is happening in Canada and the US, but our laws are yet to catch up. In New Zealand, successive governments have passed child protection laws which ignore rangatiratanga and fail to reflect te Tiriti. They have often claimed that doing so would be too complex, but this is simply not the case. Our child protection laws can, and should, start from a place of rangatiratanga. Reference to tino rangatiratanga in the principles of the Oranga Tamariki Act would be a good start, and genuine power sharing would be an important next step, but the ultimate goal should be a transition towards the “by Māori, for Māori” system described by the Waitangi Tribunal in 2021.

The opposition to the repeal of section 7AA should therefore continue, despite the government’s plan to retain strategic partnerships. The organisations within those partnerships do vital work for tamariki and whānau, but those agreements still fall short of what is envisaged by te Tiriti. Tamariki Māori remain significantly over-represented in the child protection system, and the repeal of section 7AA will make that worse, just as the Waitangi Tribunal predicted. But there is another way – as Indigenous peoples in Canada and the US are demonstrating. We should perhaps take greater note of that as the debate continues.