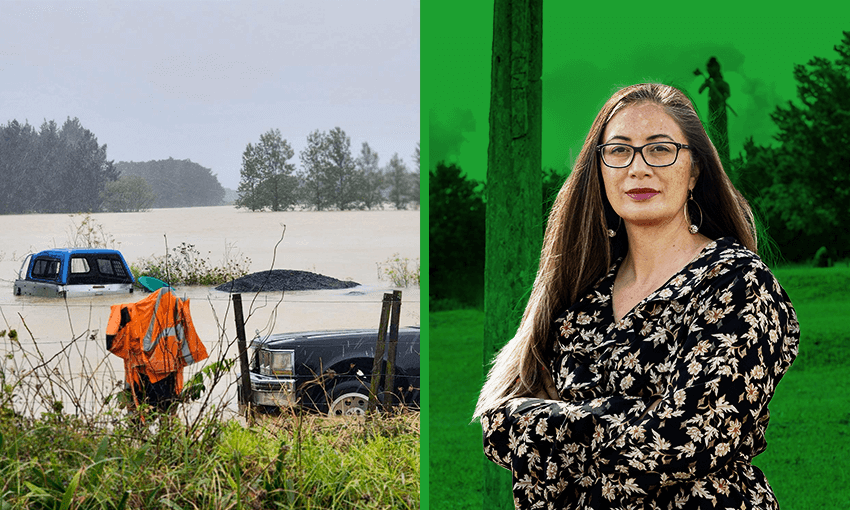

When Cyclone Gabrielle hit, the marae and haukāinga of Ngāti Wai jumped into action, offering safe haven to anyone who needed it. It was a similar story in many regions – so why aren’t Māori providers resourced in times of crisis?

Hūhana Lyndon (Ngāti Wai, Ngāti Hine, Te Waiariki, Ngāti Whātua, Ngāpuhi nui tōnu) is the Raukura CEO of Te Poari o Ngāti Wai, whose tribal rohe stretches from the Bay of Islands, through Whāngarei, Mahurangi and out to Aotea (Great Barrier). With one foot in the marae and one foot in the Green Party, Hūhana is able to see and describe up close the ways in which systemic inequity is playing out in the climate crisis.

As told to Nadine Anne Hura. This article is the third in a series of short features profiling New Zealanders who are often overlooked in news coverage.

Before the cyclone hit, we knew which papakāinga wanted to open and provide a space for those who might need to evacuate. We learnt a lot through Covid about how to work together as a hapū, and we knew that if we could just front-load our marae with resources, whether a dollar in their bank account or a load of shopping, they would be prepared. We know which areas are prone to flooding and where the slips are likely to happen, so we mobilised around that knowledge.

Marae aren’t considered “official” civil defence hubs, so there isn’t any government funding. That was a constraint and a challenge for us. Official agencies like health and social services didn’t come in until after the storm, but marae and haukāinga were on the ground from the start.

It’s a special tribute to marae, you know, that in times of crisis, we open our doors. People are at the heart of everything we do. The genealogical connections between us are our strength. It doesn’t matter about tribal boundaries. It’s all about the aroha and manaaki.

Each of our kāinga move in different ways. Some marae were delivering hot meals to our kaumātua who wanted to stay home. Others were taking in families who had to evacuate. Marae that had generators were a lifeline to many. They were humming and it was beautiful to see. That’s something we really learned, about the power of self-sufficiency.

Some marae are well connected with civil defence (CDEM) and were working together. Not all CDEM co-ordinators have strong connections into Māori communities, but we can help fill in the gaps. CDEM’s role is often one of conduit, sharing knowledge and information. When it works well it can be a well-oiled machine.

In Whangārei city, it was a different story. The CBD was evacuated, including the homeless shelter. In Covid times, our homeless were taken care of. These are whānau who live in the shadows, on the fringes, in the bushes and under bridges. How were they meant to cope in a cyclone with gale-force winds and when the bridge they sleep under floods?

Our urban marae, Whangārei Terenga Parāoa, were there. We had families who’d evacuated, elders who were lonely, kaimahi from the homeless shelter and other agencies from time to time, we even had freedom campers parked up next to the marae for security. People in the community were driving down dropping off kai, we had local nurses coming in to assist. It was a safe haven for everyone – and yet it was branded as a homeless shelter.

There was even a note on the civil defence Facebook page sending homeless people to the marae, whereas Kensington Stadium was presented as the official civil defence hub.

I ended up going up to Kensington Stadium to have a look. I’d heard some people had been turned away so I went to ask them what the story was. They had their camper beds set up, it was all kitted out, but there had only been about three whānau come through. I asked them why they wouldn’t send some of their resources down to the marae. I said we needed blankets and dry clothes and they said we should send our whānau up to them. That upset me. Terenga Parāoa was full and performing the same role as civil defence and yet it was only considered a “community response”.

I really want to acknowledge our kaimahi Māori within councils and inside the government. They are really good, trying to understand what was happening in our kāinga and translating the issues back into the machinery. They are an important link and need to be strengthened. But really, hapū and marae need to be brought into the conversation much earlier, so that we can be partners. We shouldn’t have resources sitting in a stadium with few people when others are in need and going without.

This situation is really hard to take because the only reason we’re in this situation is because of acts and omissions of the Crown. Our rivers have been altered, our wetlands drained for farms, our food basket contaminated with silt and tiko, we’re surrounded by developments that aren’t ours. We’re on remnant pieces of land prone to flooding because the government didn’t uphold its Te Tiriti obligations.

The tribes of Whangārei own only 4% of the land. Whangārei city is built on whenua raupatu (stolen land). When you’ve only got a little, you’re living on the edge of things and it’s very difficult to build an economic base to be self-sufficient and to thrive.

We might have to retreat, but retreat where? You can’t just rate us off the whenua. You can’t red zone us because there’s nowhere to go. This is an equity issue. A lot of whānau have lost everything but they don’t have insurance, so the conversation about insurance is irrelevant to them. It’s the same with our homeless whānau. If you didn’t have a home to lose, then what is there for the government to compensate? The government is prepared to compensate West Canterbury Finance over a billion dollars, but how do you compensate a landless people? What we are asking for as ngā hapū me ngā iwi o Te Tai Tokerau is simply fair and equitable access to the resources to support our kāinga and marae to prepare and respond in times of crisis.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.