Gang members say it will create more problems, but the government argues it’s about improving public safety, explains Stewart Sowman-Lund for The Bulletin.

To receive The Bulletin in full each weekday, sign up here.

New anti-gang rules now in force

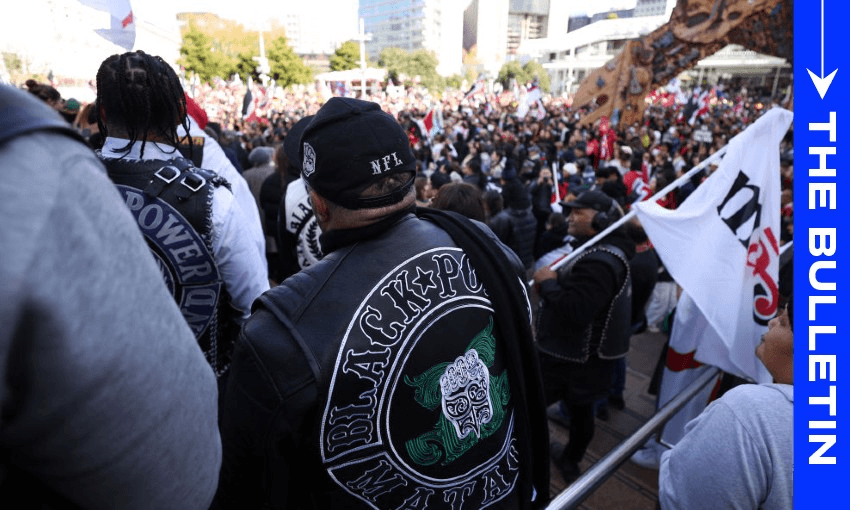

On Tuesday, patched gang members were pictured walking alongside members of the community as part of the nationwide hīkoi to parliament. There was a large police presence at the event and nothing happened. But now, new anti-gang rules are now in place as part of the government’s “tough on crime” crackdown – and that would mean those gang members at the event would have been breaking the law. As The Spinoff’s Alice Neville explains comprehensively this morning, the new legislation will see police given powers to “to disrupt and directly target gang activity”. That includes the outlawing of gang insignia in public, but also means police can also issue dispersal notices and courts can issue non-consorting orders. Gang membership also becomes an aggravating factor in sentencing.

As Newsroom explained at the time, the government also widened the law at the last minute to allow police to arrest people for insignia kept in their home in certain circumstances.

Ahead of the law being passed, police issued a direct warning to gang members to leave their patches at home, saying officers were as ready as they possibly could be to enforce the rules. Though, as Stuff’s Marty Sharpe reported, some front line officers have expressed concern that the new legislation could stretch resources. “We just don’t have the staff to implement it. That’s the biggest thing. The gang members will still wear their patches. The concern is that there’ll be a shitfight and we just don’t have the staff to deal with it,” one officer, speaking anonymously, said.

The ‘free ride’ is over, says government

The government has framed these new rules as an attempt to end public fear, declaring that the “free ride” for gangs was now over. Police minister Mark Mitchell argued in an opinion piece for the Herald that gang patches were designed to “intimidate” and that outlawing them will make New Zealanders feel safer. But the opposition has claimed that ditching patches won’t stop gang members committing criminal acts, nor convince anyone to leave a gang, and could instead risk pushing marginalised communities further to the fringe. In comments to Bridie Witton for ThreeNews last night, Te Pāti Māori co-leader Rawiri Waititi believed it was an “attack on the disenfranchised and marginalised”, while Labour leader Chris Hipkins said it was simply about optics. “This is a measure by the government to look tough on crime,” he said.

The government’s move to outlaw gang patches and clamp down on gang consorting follows similar action taken in Australia, where some believe gang activity has been driven underground as a result. Others, however, say the outcome has been a stronger perception of public safety. As reported by Newsroom’s Laura Walters, new police research released on the eve of the ban coming into effect here provided evidence against a suppression approach to policing gangs.

‘It’s about identity’

Those actually in gangs have had a mixed response, understandably. In an interview with RNZ, a senior member of Black Power said that what gangs wore wasn’t the problem. “It’s people’s behaviours, be it gang members or not, at the end of the day when it comes to the law, you do the bloody crime, you do the time.” Back in October, E-Tangata’s Tiraroa Reweti interviewed several gang members who she had spent time studying with. One, who was kept anonymous, compared gang patches to a military badge. “It’s about identity,” they said. “Getting a patch identifies someone who’s gone through the hardships of prospecting and they’re now part of the pack.” Mongrel Mob member Ching Poipoi also expressed concern to RNZ that gang members may get into altercations with police in order to keep their patches and risked damaging any positive interactions with officers. “I can see some of them doing horrible things for it, you know what I mean, not just us, there’s a lot of other gangs you know. Some of them will probably die for it,” Poipoi said.

But back in July, for the debut episode of ThreeNews, host Samantha Hayes spent time with members of Black Power Movement Whakatāne. Genesis Te Kuru-White, the chapter’s leader, said his father had helped create a 100-year road map for the group that included a plan to to make the patch a thing of the past. “He said to me, my brothers, my cousins, all of us, that one day the patch would become something of the past.”

Gang expert Jarrod Gilbert warned in an interview with The Post that some gang members will simply opt to substitute patches for something else: “That may mean more tattoos, for example. I personally don’t think a person is going to be any less intimidated by a guy with ‘Mongrel Mob’ written across his face than they would a person with a patch on.”

New police commissioner named

Meanwhile, the country’s new police commissioner was announced yesterday. Richard Chambers takes over from Andrew Coster, who has gone on to lead the government’s new social development agency. According to RNZ, Chambers has long aspired to take on the position of top cop and is popular with frontline officers. At a press conference yesterday, as reported by the Herald’s Adam Pearse, Chambers said an “absolute focus” on core policing was a top priority for him over his five-year term, which formally begins on Monday. He said it was important to focus on “doing the basics well”, and wanted to support the wellbeing of those working on the frontline. In a clear change of direction from his predecessor, Chambers said he didn’t talk about “policing by consent”, but instead wanted to bolster “trust and confidence”.

Coster, who came under fire from National while in opposition for a purportedly “woke” approach to policing, argued in favour of getting public support for the role of police. He told E-Tangata in 2023: “We rely on the support of most of the community to be successful and that depends on the way we operate and on the extent to which people feel that they can trust us and that what we’re doing is appropriate.”