Investigating a 118-year-old mystery about Wellington Zoo.

Last week, while researching for my column about Begonia House, I read the Wikipedia page for the Wellington Botanic Garden, where I stumbled upon this little nugget: “Some animals were kept at the Botanic Garden prior to the formation of Wellington Zoo in Newtown in 1906, including the ‘City Emu’ which died shortly after being relocated to the Zoo from the garden.”

When I followed the sourced link, I discovered something shocking: the city emu didn’t just die, it was murdered. (Allegedly.)

I spent days obsessively searching through PapersPast for any references to the emu to piece together the full story.

Let’s start at the beginning.

The Wellington Botanic Garden officially opened in 1869 as a public leisure ground and research station for scientists to test how introduced plants would respond to New Zealand conditions. From the early days, the garden contained small animal enclosures for pheasants and fowls and for a time, monkeys.

In 1905, Wellington city councillor George Frost acquired an emu on behalf of the city from the Canterbury Acclimatisation Society. It was kept in a paddock with a tin shed at the botanic garden near the caretaker’s house – probably about where Begonia House sits today.

The emu’s conditions were not ideal. A letter to the editor in March 1906 described a visit to the garden. “We came upon a poor Australian emu, encaged in a plot of ground about 9ft x 5ft, absolutely bare of all herbage and with very little chance of getting much sunshine – the two latter items being most essential to the existence of such a bird as an emu. And who ever heard of an emu being given a tin house to live in?”

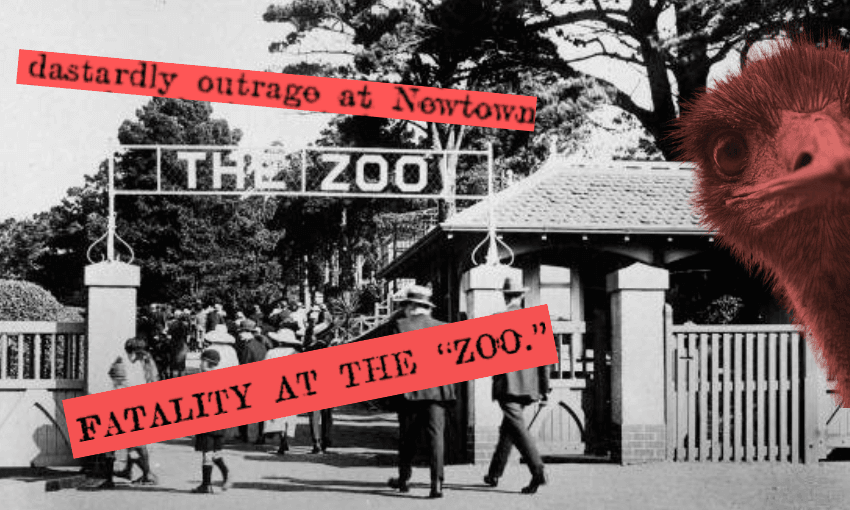

On April 23, 1907, the emu was transferred from the botanic garden to the newly opened Wellington Zoo in Newtown, where it had a large wire-netting enclosure. Ten days later, on Friday, May 3, the bird was found dead.

On Friday, May 8, The New Zealand Times reported the death with the dramatic headline and lede, “Fatality at the Zoo – The city emu is dead.” It became a national news story and was picked up by 32 newspapers around New Zealand. “It really seems as if the death of the emu at Newtown Park were a national loss, there is so much being said about the subject,” a New Zealand Times article opined.

Professor Harry Kirk, the inaugural chair of biology at Victoria University, examined the body. His report said the bird “had sustained two severe blows by some means or other – one on the body and one on the lower part of the neck – blows that might have been caused by a heavy stick or a stone”. The emu’s neck was ruptured with a three-inch wound. George Glen, Wellington’s director of parks and Rreserves, said he found “many large stones in the enclosure that were foreign to the place”. The evidence seemed to suggest the bird had been stoned to death.

But then, an alternative theory arose. Alfred Williams, an inspector for the SPCA, performed an autopsy and concluded that the emu died of natural causes: “The emu was 30 years old and had been ailing with colic for three days before death. The discolouration of the skin was probably due to inflammation.”

George Frost, the city councillor who originally acquired the emu for the city, was certain that Williams’ theory was wrong. He wrote to the Canterbury Acclimatisation Society asking for more information about the emu. C. Riders, the society’s curator, replied, saying, “I am very pleased to be able to inform you that the emu you got from us was quite a young bird. The lady who gave it to us says that she thinks it was just over four years old; she was sure it was not five years old.”

Theories about the emu’s death swirled across Wellington. The Evening Post blamed it on “some evilly-disposed person, or some boys”. The New Zealand Times said the death “points to a wicked act of cruelty practised on a harmless bird, and if the culprit could be caught a term of imprisonment would not be too much punishment for such a grossly inhuman act”. No one was ever caught, and the cause of death was never confirmed.

In July that year, an editorial in the Evening Post said, “The debate had one value; it did not prove conclusively how the unfortunate bird’s days were brought to a sudden end, but it did show something more important – the existence of a strong public interest in the zoo.”

After reading dozens of 118-year-old news reports about Wellington Zoo, I’m convinced that the SPCA inspector was wrong and the emu was almost certainly stoned to death. Why? Because there’s a pattern of behaviour. Between 1906 and 1909, Wellington Zoo dealt with a long list of animal abuse incidents:

- A man stabbed a kangaroo with a pocket knife because “the hooligan wanted to see the ‘kangi’ skip away vigorously”.

- A man was caught burning a monkey with a lit cigar and responded “It doesn’t hurt him, does it?”.

- People stuck needles into sticks so they could poke the monkeys – one of which was found with an abscess in its arm caused by a broken needle.

- A woman commanded her dog to attack the monkey cage. “The spectacle of frightened monkeys delighted the female tormentor.”

- A group of men were spotted feeding cigarettes to black sheep

- People threw lit matches at a tuatara to try to get it to move.

- Two small boys poked a wallaby with a pen knife to make it hop.

- Visitors smashed a nest of waterfowl eggs.

- Someone stole some rabbits from the petting zoo.

- Someone hit an Australian bittern with a stick, breaking its neck.

- A boy was caught firing a catapult at caged animals.

The string of incidents sparked a city-wide moral panic. The Citizens Zoological Gardens Committee held public meetings about the issue, where people were quoted as saying, “The mania of the young people of this country is to kill, kill, kill,” and “The hooligan insists on having a wilderness. Unless some of these destroyers are caught and severely punished as a warning to others, the friends of the zoo may naturally ease off their benefactions.” Another person said, “What good is it to place birds and animals in Newtown Park for the cruel and vicious to torture?” In 1909, the SPCA appointed two special constables to police the zoo.

Thankfully, the animal abuse seemed to die down after a couple of years as Wellingtonians got used to having a zoo. Perhaps, when presented with novelty, people have some strange instinct to break things – the same way everyone threw e-scooters into the harbour when they first arrived. Or perhaps humans are just the worst.