Why demolishing the bridge would make Te Ngākau Civic Square a much better public space.

Earlier this month, Wellington City Council voted to demolish the City to Sea Bridge and replace it with a ground-level pedestrian crossing on Jervois Quay. A new pedestrian bridge will be considered for funding at a later date. Councillors said demolition was significantly cheaper than strengthening the bridge to meet earthquake standards.

That decision hasn’t slowed the bridge-related discourse, though. Save-the-bridge campaigners are in full swing. A heritage or architecture group will almost certainly file a judicial review against the council, though those don’t often succeed.

On The Spinoff, Jeremy Hansen praised the bridge’s idiosyncratic design and layered bicultural elements. I argued that the bridge was a beloved icon but not worth the cost of fixing. Architect Caro Robertson argued that the bridge is too important to demolish. Last week, in the NZ Herald, Simon Wilson wrote a compelling essay describing the City to Sea Bridge as “our Eiffel Tower, except it’s more important”.

Sorry Simon, but your thesis on art and architecture has only radicalised me further. I used to think the bridge was nice but not worth saving. Now, I actively support its demolition. My reasoning has nothing to do with its artistic or cultural merits; it’s because it’s a bad piece of urban design. Te Ngākau Civic Precinct would be better without the bridge.

1. The bridge separates more than it connects

The City to Sea Bridge, as the name suggests, connects the city to the sea. On one side, you have Te Ngākau Civic Square, which is a bit of a dump right now but will be a vibrant space once the Central Library, Town Hall, and City Gallery reopen. On the other side, you have Whairepo Lagoon, Te Papa, the waterfront and a rich selection of bars and eateries.

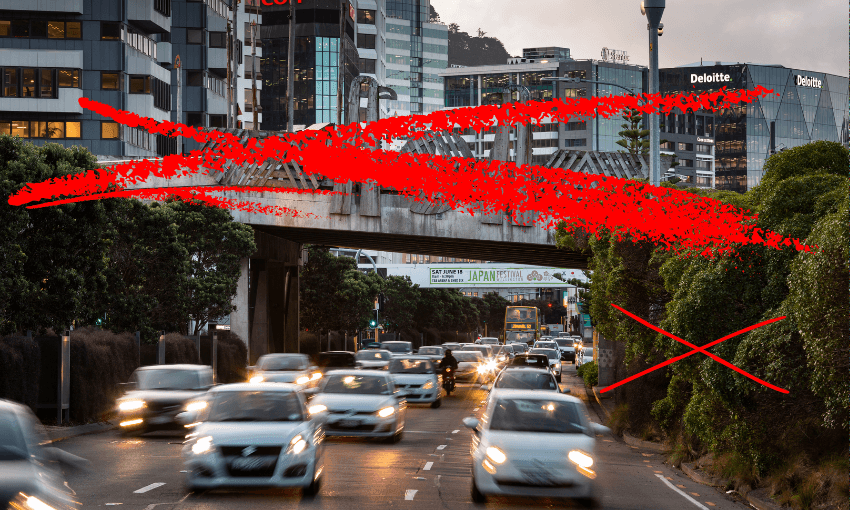

Rather than forming a connection, the bridge forms a visual barrier. They feel like two distinct areas separated by an artificial hill made of stone and wood. You can’t see Civic Square from the waterfront, and you can’t see Te Papa from Civic Square – you can barely make out of the lagoon.

Replacing the bridge with a ground-level pedestrian crossing will open up the area by creating a continuous flow of flat public space without visual interruption. Rather than two nice public spaces, it will be one larger and truly world-class precinct.

2. It inconveniences pedestrians

Replacing a beloved footbridge with a traffic light pedestrian crossing may not sound like a win for urbanism, but it is. Remember what the City to Sea Bridge crosses over? It’s not a body of water, it’s a road. The bridge was constructed as a monument to car-brained design, ensuring that automobile drivers would not have to be delayed by even a few seconds by people crossing the road.

The Global Street Design Guide, which Wellington City Council has endorsed, says pedestrians should be at the top of the transport hierarchy – and that’s especially true in busy central areas like Civic Square. But that’s not what the City to Sea Bridge does. It intentionally places cars at a higher priority than walkers.

Some pedestrians might find it slightly safer to cross a bridge than at a traffic light, but it also forces them to make a longer and steeper trip up stairs or ramps. For wheelchair users or anyone else on wheels who wants to cross Jervois Quay, the bridge turns a 10-metre flat crossing into a 220-metre quest over an extended ramp. I used to bike to work via the bridge, and most mornings, it was a pain in the arse; I would have much rather waited a few seconds to cross at some traffic lights.

Drivers wouldn’t even be inconvenienced by that much. Jervois Quay already has six other traffic light pedestrian crossings within 500m on either side of the bridge. If anything, drivers should be inconvenienced more. The waterfront is an incredible natural resource, but it is cut off from the city by a six-lane road. Ask any waterfront bar owner and they’ll tell you one of the biggest struggles is getting the people to cross the road, especially the lucrative after-work office crowd. The traffic lights should be rephased with longer and more frequent pedestrian crossing times, and every crossing should be painted with zebra stripes or some colourful street art.

In fairness to the bridge, it is more walkable than most pedestrian overpasses because it is designed with a long slope to minimise steepness. But that leads to the third problem.

3. It takes up too much space

Once a city starts developing, it’s pretty damn hard to find new space for parks and plazas, so it’s really important to hold onto the public spaces you’ve got. And yet, for decades, Wellingtonians have cheerily sacrificed half of Civic Square, the cultural heart of the city, for a long, wide ramp down from a bridge that goes over a road.

The flat part that makes up the “square” of Te Ngākau is 0.27 hectares. The area from where the steps of the bridge begin until it reaches the edge of Jervois Quay is also 0.27 hectares. And that’s not even considering the Jake Elliot Green, that chunk of grass you haven’t thought about in so long that you didn’t even realise that’s not its name. No one ever goes to the Jock Ilott Green because it is cut off from the rest of Civic Square on two sides by the bridge. The Jack Loite Green is best known for the Rugby World Cup Celebration sculpture, one of Weta Workshop’s least celebrated pieces of public art. Removing the bridge would make the John Lotto Green a cohesive part of the square, effectively tripling the usable space. We’d have so much room for activities.

It’s been a long year, and maybe I just need a break, but I hate the City to Sea Bridge and will celebrate its demise with popcorn and champagne.