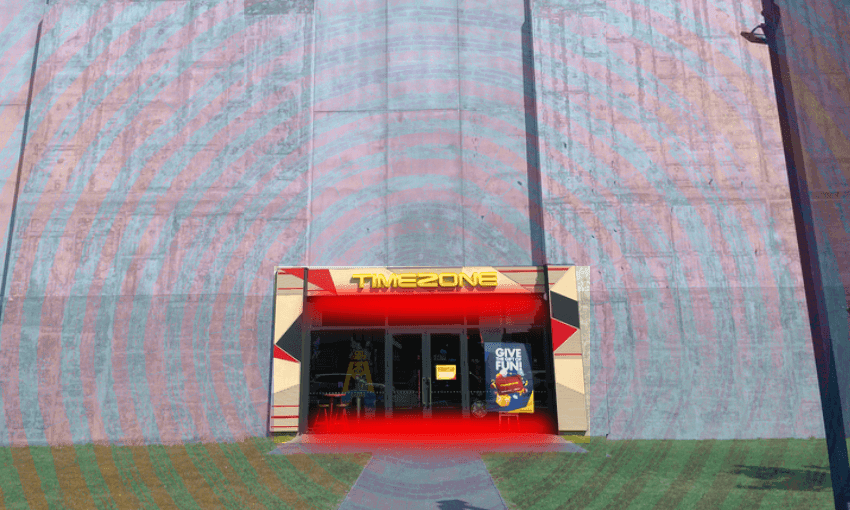

It’s become of one of Christchurch’s most famous landmarks online, but why? Alex Casey steps through the portal of the brutalist Timezone.

Ask anyone what Christchurch’s most iconic building is and you might expect to hear some of the dusty old classics like the Cathedral, or the Town Hall, or the Arts Centre. But for a growing number of locals, and hundreds of thousands of people obsessed with weird-looking buildings on the internet, a dazzlingly dystopian challenger has recently entered the arena: the “brutalist” Timezone entrance on Hereford Street.

A hallucinatory neon portal piercing through a 28-metre-high wall of concrete, the entrance to the central city Timezone arcade appears to elicit a powerful response in all those who encounter it. “I walked past this high as giraffe balls once and almost had a panic attack. Brutalist excellence,” recounted one visitor to the city. “I find this building deeply unnerving,” mused one CBD-dweller who works nearby. “It’s giving prison,” said another.

Frequently popping up on TikTok, Reddit and Instagram accounts dedicated to dystopian spaces, even those who have never seen the brutalist Timezone in real life are transfixed and unnerved by the facade. “Damn, that’s liminal,” mused one Instagram user. “I need the name of the town bc I must go to this,” one Redditor wrote. “Sci fi movie production designers couldn’t do better,” added another. “Maze Runner III – Timezone escape”.

Just as many comments wonder who – or indeed what – is responsible for the design.

‘It’s accidental architecture’

Although he is “honoured” that the building has captivated so many around the world, architect Richard Dalman has a confession to make about the brutalist Timezone – it was never part of the original plan for the building. “I can’t sit here and say, ‘yeah, look, we spent weeks, months, years thinking through that exact patterning’,” he laughs. “Because the truth is that facade was meant to have another building placed up against it and you were never meant to see it.”

The original plan for the building, which is largely used as a carpark, was that the Timezone would form a small part of a longer arcade that would run through the ground floor, all the way to Hereford Street. But when Timezone took over the entire ground floor tenancy, and the site in front of it remained empty, a makeshift “portal” was designed. “So this is all the result of the building in front not being constructed, because the demand just hasn’t been there.”

Even if it is the byproduct of the sluggish rebuild and a slow market, Dalman says the Timezone represents a kind of transience that is interesting in itself. “It has created this opportunity for the Timezone entry portal to exist in a place and space that it was never supposed to, and for those walls to be exposed which were never, ever supposed to be exposed,” he says. “It’s a kind of accidental architecture, which is really quite pleasing.”

Dalman encourages people who are drawn to the Timezone to also look at the more “architecturally articulated” facades which are just around the corner – AKA the ones that were actually designed to be looked at. “We’ve got these curving black metal panels which are inspired by the eels in the Avon,” he explains. “So it’s really interesting that people are picking up on the plain concrete facade, and not the one that we put all our time and effort into.”

‘We should use it for an album cover’

Regardless of whether the Timezone was intentionally part of the creative vision, the facade has already influenced artists working in other disciplines across the city. The debut album of Ōtautahi noise band Les Fuzz Minou, released this month, has a Tagalog title: ‘Fuza – Naknampucha Gumuho Na Naman Ang Kalawakan Dahil Sa Deputang Brutalistang Timezone Na Yan’. Broadly translated into English? A Cosmic Trip to the Brutalist Timezone.

Les Fuzz Minou bassist Robin remembers his first encounter with the Timezone, which popped up sometime in 2023, very well: “Me and some of the guys were just walking down Hereford Street, and suddenly there was this little tiny Timezone right there in the middle of this giant concrete wall.” Entranced by its “mystical qualities” that evoked “a time gate to Soviet Russia”, the band knew: “We should use it for an album cover some time.”

Local artist Dark Ballad, aka Joe Clarke, jumped at the opportunity to immortalise the brutalist Timezone for Les Fuzz Minou. “I think it is probably the coolest-looking thing in Christchurch at the moment,” he says. “It’s very dreamlike to have this huge concrete wall and then this little cut-out of something which feels like it is from the past buried in there.” Because as futuristic as it looks, Clarke says there is a feeling of nostalgia lurking beneath it all.

“I used to go to the old Timezone on Colombo Street everyday to play pool and Street Fighter,” he adds. “And after the earthquakes, it was just all gone.”

Playing on those themes of the past and the future, Clarke created a woodcut design of the brutalist Timezone for the album cover. Printing a limited run of 50 copies by hand in his New Brighton home, he says each rendering of the Timezone will look slightly different to the last. “And if you look closely, you can actually see there are things inside the Timezone. In my vision, it is this dark and mysterious arcade that has been abandoned for years and years.”

‘More than just bare concrete’

While “the brutalist Timezone” has become shorthand for the Hereford Street entrance, architectural historian Jess Halliday says there “is a heck of a lot more than just bare concrete” to the movement. “It’s so awesome to see this engagement with the city but, to me, it’s not actually brutalism,” she laughs. “Yes, concrete is a feature of that period of architecture, but just because you’re wearing a woollen coat, it doesn’t make you a sheep.”

Halliday says that the brutalist movement, which influenced the design of many Christchurch buildings during the middle of the 20th century, was “largely about expressing a building’s architectural essence – its structural truth, its material truth, and the truth of its internal organisation.” These expressions can be found nearby in the “big chunky exposed frame” of the civic building, or the “soaring columns” of the Town Hall.

Even if it’s not technically brutalist, Halliday says the Timezone has the movement to thank for legitimising concrete as a material. She also has no doubt that it has cemented its place in Ōtautahi’s architectural history. “We’re coming up to the 14th anniversary of the big earthquake, and we’ve still got this city that is constantly shifting and moving, and now the Timezone is a part of that experience of being in this transitional city,” she says.

Dalman agrees. “It’s not an intentional experiment, but it is an opportunity to see our city in a different way, with buildings being demolished and being built all at the same time. It’s also an example of how the earthquakes have changed our view of the city – we get to see big sides of buildings which normally wouldn’t be seen at all.” And while he says there is a “good chance” something will be built in front of the entrance soon, things can always change.

“Who knows,” he adds. “The council might decide to buy it and turn it into a park, all because there’s so much demand from overseas tourists coming to look at the Timezone.”