Last weekend, Spark Arena hosted Aotearoa’s largest gaming festival. Sam Brooks attended to see what all the fuss was about.

“ALL YOUR LIVES HAVE LED TO THIS.”

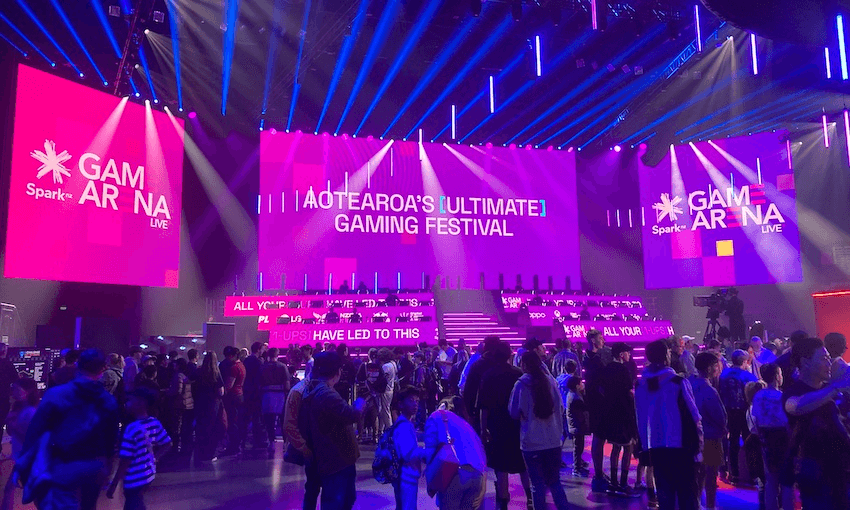

This slogan was emblazoned across multiple screens inside Spark Arena this past Saturday, as a couple thousand people attended the country’s “largest gaming festival”. Inside the main arena, lights flashed over booths where people played Playstation, Xbox and PCs alike. Outside that space, dotted around the hallways were smaller booths – retro arcade machines, a Just Dance dance floor and a small ring dedicated to local games (including a prime spot for local game Guardian Maia).

Despite the megachurch vibe of that slogan, the mission of Saturday was clear: Spark Arena was a place for games, and the people that love them.

One of my most formative gaming memories was at Armageddon, back when it was hosted at the Aotea Centre. I stood in line for 45 minutes for the chance to play literally 15 minutes of Final Fantasy X. Even though I’ve spent hundreds of hours with that game in the two decades since, those initial 15 minutes were electric. It wasn’t the game; it was the feeling of getting a sneak peek at something, a glimpse behind that particular wizard’s curtain.

Festivals like this – conventions or expos, really – have a tension to work through. On the surface all the marketing might be about having fun and being among likeminded people who just want to game, but at its core it is still a marketplace. The gamified aspect of the convention, where participants were tasked with finding and scanning QR codes around the arena, really hammered this home. People were literally rewarded and ranked based on how much product they engaged with.

It should not be a massive surprise that a gaming convention was gamified, however. The games sector has a similar tension to work through, which you’ll see in how it is treated in media across the world. Is it culture? Is it business? Is it tech? Is it all three? (After reporting on this sector for a decade, I can confirm it is all three. And yeah, that’s confusing.)

That’s for an adult to think about, though, not a child. When I think back to my own Armageddon experience, I don’t remember any of the logos. I don’t remember that it was as much a marketplace as it was a place to play a bunch of games for free, and maybe get some other free stuff (although, of course, there was a ticket price). I think about playing the game with the best graphics in the world and the rush of that. Kids see lights, not logos.

The highlight of the morning was undoubtedly the Rise Cup, a three-round Fortnite tournament with a total prize pool of $240K. First prize? $35,000. The MC, Ellieonthetelly, did her absolute best announcing 50 screen names that were definitely not meant to ever be read out loud, and kudos to her for the wide-eyed enthusiasm she brought to introducing “Jakethedog7” and “doglover21” onto the stage. After which, those 50 competitors played in front of a massive screen, stone-faced, while commentators in the bleachers spoke at a pace that should be expected at an event sponsored by Red Bull.

The tournament was also a demographic reflection of the festival, more generally. All 50 of the competitors were male-presenting, although a fair amount of them actually played with female-presenting skins. A quick ask of someone more acquainted with Fortnite than me confirmed what I’d assumed; female skins are smaller so are harder to spot, and therefore to shoot, in the game. It’s just like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie said: “As women we learn to shrink ourselves, to make our hitboxes smaller.”

While it was a slightly surreal experience for me – I will never be able to take commentators saying with straight faces, phrases like “my boy Soy Palace” or calling the players “experts in their craft” – I realised that for the bulk of people in attendance this was pretty normal. When I grew up, games were a thing that happened in the home, either by yourself or with people in the same room as you. They were absolutely not broadcast in arenas with money on the line. If you’ve grown up with games as things you can access anywhere, at almost any time, for free or close to free, a tournament like this is an easier pill to swallow.

By the end of the three games, SFG Falcon emerged victorious. A teenaged boy ambled from his computer to the front of the stage, mumbled a few words, and took his trophy. Gaming changes, gamers remain the same.

Down the other end of the arena, younger kids of all genders played Fall Guys, a demonstrably more wholesome game than Fortnite, and maybe a sign of where the future is. Or at least some of the future. Throughout the entire day, the only women I saw on the main stages had been paid to be there, which is some kind of progress, I suppose.

The latter half of the day, which had an R16 age restriction, frankly, lacked the enthusiasm of the morning. Adults are simply harder to whip up into the level of furore that a festival like this needs, and the choices of games on display on the big screens in the main arena – NBA2K25 and Valorant – are less visually chaotic than Fortnite, and not as fun to watch. At one point I scanned across the bleachers to see who was actually watching the massive screens and spotted barely more than a hundred.

Adults are savvier, and more cynical than kids. We know we’re being marketed to. We know what we want to line up for and what we don’t. We’re less likely to be tempted by gamification. It felt clear that the convention had been set up more for kids – and kids at heart – than for adults. William Waiirua, the MC for the NBA2K25 tournament, did his best to try to whip the audience into some kind of frenzy, but alas. The grown-ups were there to game, not to vibe.

On my way out of the afternoon session, I swung past the arcade machines. These were dotted throughout the outside of the main arena, and featured classic games – Pac-Man, Mortal Kombat 2, Point Blank, Street Fighter 2. A group of dudes in their 20s gathered around Street Fighter 2, playing it with the same level of giddiness that people have played it with for decades. Gaming might be culture, it might be tech, it might be business, but so long as it’s fun, isn’t that what really matters?