The prime minister says New Zealand has a culture of saying no to growth. When it comes to housing, he’s part of the problem.

Windbag is The Spinoff’s Wellington issues column, written by Wellington editor Joel MacManus. It’s made possible thanks to the support of The Spinoff Members.

“There’s always a reason to say no, but if we keep saying no, we’ll keep going nowhere,” prime minister Chris Luxon declared in his state of the nation speech on Thursday. “The bottom line is we need a lot less no and a lot more yes.”

His speech painted an aspirational vision for New Zealand, where major industries are turbocharged with greater development, competition and overseas investment. You’d be hard-pressed to find anyone, regardless of their political leaning, who thinks New Zealand doesn’t have a problem with growth. His central diagnosis of the problem is that well-intentioned regulations have morphed into barriers that stymie investment. As Luxon put it, “Too often, when it comes to economic growth, we’ve slipped into a culture of saying no. It’s always easy for someone to find a reason to get in the way and find a problem – but we need to shift our mindset and embrace growth.”

Luxon highlighted two specific examples: the Port of Tauranga, which has spent years battling for planning permission to expand, and concerts at Eden Park, which remain restricted by council rules. In both cases, local residents and groups have raised concerns about noise, health and quality of life. While these concerns are understandable, Luxon argued, the impacts are small and localised, vastly outweighed by the broader economic benefits that would flow to all New Zealanders.

For an example of just how pervasive this “culture of saying no” has become, consider the Quarterdeck complex. A developer, Box Property, purchased a disused service station in Cockle Bay, Auckland, and planned to transform it into a modern townhouse complex with 70 homes in buildings ranging from two to four storeys. It would have stimulated economic growth by providing much-needed housing in east Auckland and added more customers for local businesses. The construction itself would have created 177 full-time equivalent jobs over two years.

It was exactly the kind of economic growth opportunity Luxon extolled in his speech. But the Cockle Bay Residents and Ratepayers Association said no. They raised concerns about too many cars parking on the street, so the developer included 102 basement car parks. Then, residents worried about increased traffic. Later, the residents’ group shifted their argument to suggest (with little evidence) that the pipes wouldn’t be able to handle wastewater from another 70 homes.

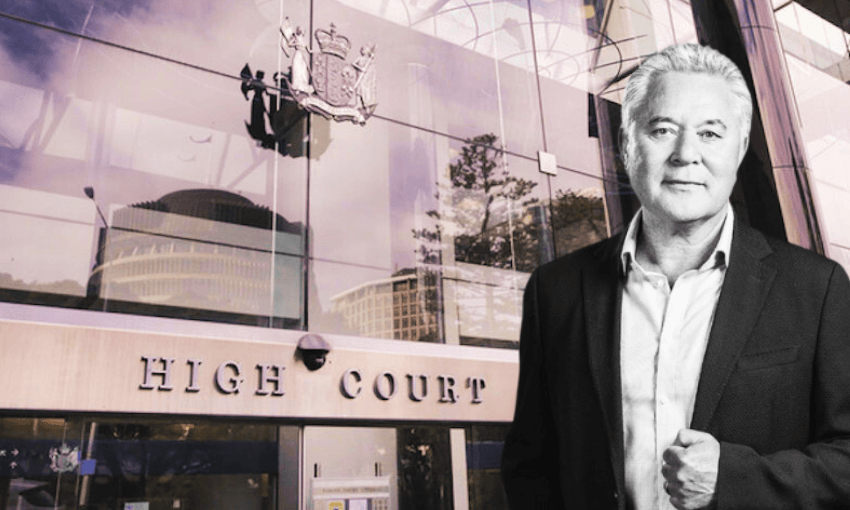

The local MP joined the residents’ association in opposing the development, launching a campaign to block it. For him, it was a nostalgic cause; he had attended primary school just across the road from the derelict service station. “I remember this place really well,” he said in a Facebook video from 2020, warning residents of developers who wanted to “plonk multi-unit dwellings” in their neighbourhood. “There are other parts of Auckland that make sense for us to put higher-density dwellings into… this is an area that should always stay a single-dwelling zone”. He praised the residents’ association for their anti-growth stance, declaring, “They’ve been doing a great job fighting back on this. They deserve a medal.”

That MP’s name, in case you hadn’t already guessed, was Christopher Mark Luxon.

In 2024, the Environment Court declined fast-track consent for the Quarterdeck development. Today, the site at 30 Sandspit Road, Cockle Bay remains a vacant service station, fenced off with chicken wire. An investor sought to inject significant funds into the Cockle Bay community, but New Zealand’s culture of saying no made it impossible.

This same story has played out countless times across the country. Instead of welcoming property developments as investments in their communities, residents’ associations treat them as invasions threatening the local character. They often make the same argument that Luxon did – that other areas are better suited to development, and their neighbourhood should remain untouched. The problem is that when every neighbourhood says this, new homes don’t get built anywhere.

This is happening right now in Wellington with the Mayfair development in Mount Victoria, where some residents argue a new seven-storey apartment block will ruin the area’s character. In this instance, however, the opposition is unlikely to succeed, thanks to critical policy reforms that have challenged the culture of saying no to new housing. These include the new Wellington District Plan, the Auckland Unitary Plan, and the National Policy Statement on Urban Development.

The most significant policy change of all was the Medium Density Residential Standards – a bipartisan agreement between National and Labour allowing three-storey townhouses on most residential land by default, without requiring developers to seek complex planning permission or fight with local community groups. It was a world-leading response to the housing crisis, but it collapsed in 2023 when National withdrew from the deal. Why? Because of a decision by the party’s new leader, Christopher Luxon.

It’s a hard thing for a politician to admit they were wrong, but Luxon should consider listening to his own words: “It’s always easy for someone to find a reason to get in the way and find a problem – but we need to shift our mindset and embrace growth.”