Parliament’s justice select committee held the first day of submissions on the Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Bill on Monday. Lyric Waiwiri-Smith and Joel MacManus report from parliament.

It’s the bill that inflamed a nation. It triggered the largest protest in New Zealand history. It smashed the record for public submissions and crashed parliament’s website. And now, the most anticipated select committee hearing parliament has ever seen.

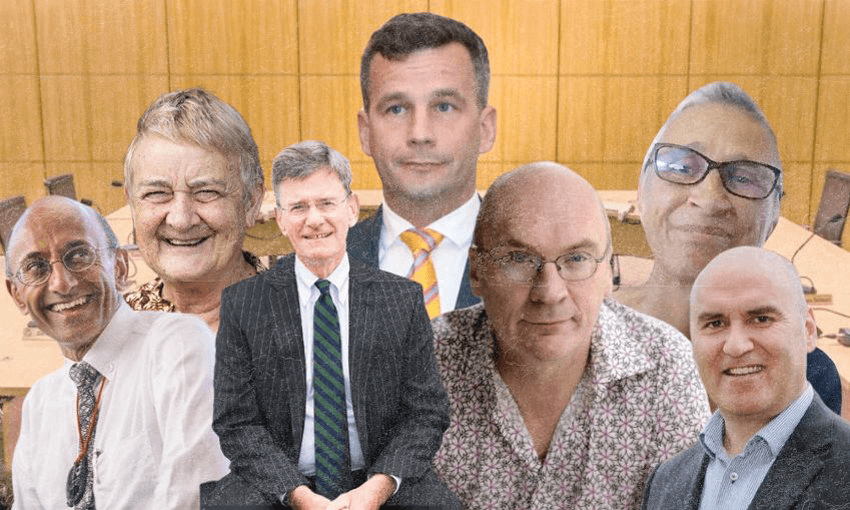

Over the next month, the justice committee will hear more than 80 hours of oral submissions from top lawyers, historians, community leaders and activists. It began on Monday with eight and a half hours of submissions, breaking only for half an hour at lunch.

It was a relatively dry and procedural process for an issue that has stirred such great passions. Select Committee Room 3 looks as if it were architecturally designed to be as boring as possible. The design had a calming presence on everyone in the room. The committee sat at an oval table, with chair James Meager at the head, and each submitter, in turn, sitting opposite him. At the end of the room, 40 seats were laid out for media, submitters and the occasional member of the public who came in to watch.

Questions from MPs were sharply pointed at times but never aggressive. Green MPs Steve Abel and Tamatha Paul, Te Pāti Māori MPs Debbie Ngarewa-Packer and Tākuta Ferris, and Labour’s Duncan Webb were particularly enthusiastic. The government MPs (Rima Nakhle, Cameron Brewer, Paulo Garcia, Jamie Arbuckle) on the committee were mostly silent throughout, though Act’s Todd Stephenson and National’s Joseph Mooney chimed in from time to time.

8.30am: ‘The British, you mean?’

The room was packed in anticipation of the first submission from the man spearheading the bill: Act leader David Seymour. In his allotted time, Seymour said that New Zealand had been split into two groups, “land people and treaty people”. As an example of this division, he referenced a concert in Christchurch hosted by a community group which originally featured racially-tiered ticketing – though that was a private event and in no way related to the Crown’s treaty obligations.

Seymour repeatedly conflated Te Tiriti of Waitangi with affirmative action policies – even suggesting Holocaust survivors in New Zealand were disadvantaged by the treaty because they were not Māori. There was a small media frenzy when he suggested that pre-European New Zealand was not a sovereign nation capable of signing international treaties. “The idea that there were two sovereign nations, I’m sorry, I don’t subscribe to that,” he said. The British Crown recognised New Zealand as a sovereign nation in 1835 following He Whakaputanga (the Declaration of Independence).

“Some say this bill will not pass this time – we shall see,” he said. He pointed out that the abolition of slavery in the UK, homosexual law reform and end-of-life choice in New Zealand didn’t succeed on their first attempt either.

Despite telling reporters outside the room he’d be keen to hear submissions and have his mind changed, he left swiftly out the door, followed by a crowd of journalists, disrupting the beginning of Te Kōhao Health and the National Urban Māori Authority’s submission led by Lady Tureiti Moxon. “We have to sit here and listen to people telling us we don’t belong here,” she said to the thinned-out room. “[This bill] is designed to subjugate, humiliate and oppress Māori”.

Gary Judd KC, barrister and uncle to Seymour, was the first of the submitters to speak in support of the bill. He urged parliament to use its powers to put a definition of the Treaty into legislation, because “parliament should be jealous of its sovereignty.”

He said the interpretations of the treaty have changed over the course of history at a “whim”. Labour MP Duncan Webb asked how the Crown could have asserted sovereignty when parliament hadn’t been established until 1854. When Judd allowed for too long a pause, Webb replied with a short, “Yeah, OK.”

“Do you think it’s OK that one group changes the deal without informing the other?” Ferris asked. “Well, no, I don’t agree with that characterisation because it’s impossible to categorise a collection of warring peoples—” Judd began, and Ferris didn’t miss a beat: “The British, you mean?”

Ngāti Toa rangatira chief executive Helmut Modlik said parliament had established itself on his iwi’s territory. “Ngāti Toa refutes the power of parliament.” He said it was a “logical impossibility” that his ancestors would have ceded complete sovereignty. He described Seymour’s attempt to conflate the Treaty of Waitangi with all race-based policies as a “shameful race-based dog whistle.” Asked to reflect on the leadership of Christopher Luxon, Modlik laughed: “You’ve asked me to step on a landmine here.

“The biggest question for every society is ‘who decides?’ and ‘who decides who decides?’”

9am: ‘Everyone has these rights, but it hasn’t always happened’

Treaty expert and collector Spencer Scoular, who told the committee he was there as a voice for the Treaty, presented several original documents, including the official English translation that was sent to London to be ratified. He argued that the English translation differs so severely from te Tiriti that there may not have been an agreement at all. Tākuta Ferris pointed out that this reasoning was flawed, as international law always prioritises the language of the indigenous people when interpreting agreements such as Te Tiriti.

Lawyer Graeme Edgeler focused on the third proposed principle, which aligns with the third article of the Treaty, granting all individuals equal rights. This was a distraction, he said. Individual rights were already entrenched in several other pieces of constitutional law. The Treaty principles should relate to relationships between the Crown and iwi. Act MP Todd Stephenson asked how he felt about Article 3 of the Treaty only granting rights to Māori. This caused some confusion. “British subjects already had the rights of British subjects,” Edgeler said, slightly bemused.

“If the bill were to pass, I believe our government would be the laughing stock of the Western world,” Sir Edward Durie said in a submission by the New Zealand Māori Council, alongside Anne Kendall, Donna Hall and Betsan Martin.

10am: ‘This whole process would be laughable’

Conservative influencer Geoff Neal stood out from the crowd. Firstly, because he spoke with the intonations of a self-help podcaster. Secondly, because he didn’t make any substantive legal points, instead he focused on polling. His presentation mostly consisted of polls showing majority support for the bill – and pre-emptively arguing that polls which found a different outcome were flawed. He dived the topic of media bias and social media algorithms, which garnered an awkward smirk from Meager, and pitied laughs from the press gallery. He concluded by claiming that only 9% of New Zealanders were Māori by blood – less than half the official census figure.

Te Kupenga Hauora Māori associate professor Rhys Jones (Ngāti Kahungunu), appearing over Zoom in front of a Toitū Te Tiriti banner, spoke in his role as a health professional. “This whole process would be laughable if it wasn’t for the serious harm it’s causing,” he told the select committee.

“Racism is a powerful driver of adverse health incomes,” he said. He drew on the “huge body of evidence” connecting exposure to racism to higher risks of mortality. “The mere introduction of this bill and the associated incitement of racist violence is having predictable health impacts. That’s making people sick … I would say that those enabling this process, even if they don’t plan to support the bill to the next stage, are complicit in that.” The prime minister has stated, on many, many occasions, that National would vote in favour of the bill at first reading but not beyond select committee.

11am: ‘This really is a case of much ado about nothing’

Former Treaty negotiations minister Chris Finlayson made a surprise cameo as the speaker for the New Zealand Bar Association. It took him less than a minute to tear into the bill, saying the principles were “not particularly well-crafted”.

He offered his own interpretation of the principles of te Tiriti. “There aren’t many principles, and they’re reasonably benign: to act with dignity towards one another, to properly consult tangata whenua, to protect their treasures, and so on. They’re pretty innocent principles; they’ve been interpreted in a very conservative way by judges over the years. This really is a case of much ado about nothing.”

Finlayson said there could be unintended consequences to the bill in instances where the Crown has already confirmed certain rights to iwi through the Treaty settlement process. “I refer particularly to the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1992. Be very careful what you wish for, because it may give Ngāi Tahu a lot more authority over Te Waipounamu, whether that is Seymour and his cohort’s intent.”

Sixteen-year-old Te Kanawa Wilson, winner of last year’s Ngā Manu Kōreo, gave his submission entirely in te reo Māori. He questioned the absence of mana motuhake for Māori within the bill, leaving a wide-open question mark over whether the proposed principles provide any protection for the self-determination of Māori.

“I was raised within the Māori language and tikanga Māori; they’re embedded in my heart,” he said. “They’re the values of my Māori world, so my thoughts, my voice is all in Māori, so I can stand with mobility and pride within my identity at all times.”

On a different note, pollster, blogger, and former National Party staffer David Farrar spoke in support of the bill. He argued for the need for parliament to decide on a definitive translation of the Treaty. “I would happily go with principles decided by parliament that I only partially argue with,” he said.

12pm: ‘There can be no racial justice for any of us’

Hauora Taiwhenua Rural Health Network’s Tania Chamberlain and Fiona Bolden spoke about poor health outcomes for Māori—in cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, life expectancy and more. “We’re in a relentless fight for equity,” Chamberlain said. “People who are Māori and rural do worse than people who are just poor and rural … We need that information to decide how we change outcomes.”

Kirsty Fong and Mengzhu Fu, from Asians Supporting Tino Rangatiratanga, opposed the bill on the grounds that “our communities are not separate but interdependent, and that our liberation is therefore interlinked”. They spoke of the rise in emboldened racism against tangata whenua, which they had observed growing within their own community.

“We see that racism in this country stems from the history of colonial racism and the treatment of Māori, and all other racism as migrants that we experience is connected to that foundational violence of colonialism,” Fu said. “If we do not address that foundational violence, there can be no racial justice for any of us.”

1pm: ‘Are you suggesting that David Lange was a racist?’

Kerry Dalton, chief executive of the Citizens Advice Bureau, expressed concern that the government was effectively rewriting the Treaty unilaterally, without the agreement or involvement of the other Treaty partner, especially given the history of breaches of te Tiriti by the Crown.

“It was distressing to hear that some of those hapū and iwi who have gone through the settlement process are now questioning the apologies given by the Crown … it means that the Crown is acting as if te Tiriti doesn’t exist,” she said.

Marine biologist Kendall Clements, one of the seven University of Auckland academics who penned a controversial letter in The Listener questioning the scientific merit of mātauranga Māori, supported the bill. He quoted excerpts from former prime minister David Lange’s Bruce Jesson lecture, where Lange argued that the government could allow Māori autonomy or iwi delegation over some issues, but “what it cannot do is acknowledge the existence of a separate sovereignty”.

“I attended that David Lange speech in 2000, and it was very disappointing at the time,” Steve Abel replied, earning light laughter from the crowd. He posed to Clements that perhaps underlying the desire to strip Māori of their rights are the traditions of colonialism, and at the root of that, white supremacy. “Are you suggesting that David Lange was a racist?” Clements asked.

Academic Elizabeth Rata, another Listener letter signee, opened her oral submission with a reference to the Education Act 1877 as an example of effective liberal democracy. It was a point that came back to bite her very quickly during question time when Webb pointed out that the free and compulsory education outlined in the Act was available only to Pākehā children until 1890. Asked by Ferris whether she could name a modern colonial society where indigenous people have thrived under liberal democracy, Rata argued that we need only look in our own backyards to the “burgeoning Māori middle class”. She said Aotearoa has two choices: to be a “first-world liberal democracy,” or a “third-world re-tribalised state”.

2pm: ‘I’ll send you some links’

Maui Capital’s Paul Chrystall pushed the claims of the English text of the Treaty, that rangatira had ceded absolute sovereignty over New Zealand. “Where does it say in the Māori text that they ceded sovereignty?” Ferris asked. “In the first principle,” Chrystall replied. “But where is it?” Ferris shot back. Chrystall hesitated and said he could not read te reo Māori. His submission ended with three minutes left on the clock.

Former policy adviser Paul Goldstone, speaking in favour of the bill, argued parliament has a constitutional right to define the principles of the Treaty. He got some shtick from Tamatha Paul after the two failed to see eye to eye on the possibility that things such as language and land must be protected too. “I’ll send you some links,” she said.

Former leader of New Conservatives Elliot Ikilei led the submission for Hobson’s Pledge alongside lawyer Thomas Newman. Ikilei began by claiming Hobson’s Pledge had initially been denied a spot to speak. This was “outrageous” and “incomprehensible”, he declared. Meager replied that Hobson’s Pledge did indeed receive an invitation to speak, but no one replied*. They ended up taking a speaking slot from another group. “Sounds like special rights,” quipped Tamatha Paul.

* The Justice Committee’s principle clerk later said Meager’s comment was based on incorrect information, and Hobson’s Pledge did reply by deadline but after all the speaking slots had been allocated.

Speaking to the substance of their submission, Newman said Hobson’s Pledge supported Principles 1 and 3 in the bill, but wanted to rewrite Principle 2 to remove references to tino rangatiratanga, defining it more narrowly as property rights. They also asked the committee to amend the third principle, keeping the reference to “equal rights” but removing the promise of “equal benefits”.

Marilyn Waring, academic and former National Party MP, mused on the meaning of “equality” in her opening remarks. “The meaning of equality is so highly contested that there’s no universal agreement as to what it means,” she said, “and this bill is based on the old approach that pretends that everybody’s born equal and that people can have the same treatment regardless of differences.” She reflected on the four generations of family farming that preceded her – land her family gained after Waikato-Tainui members were forced to desert it. “We’ve watched our families bear the fruits of the subsidies of farming, and profit – from there not being property speculation tax – and we watched how those generations talked about that,” Waring said. “They never wanted to remember that many people were murdered, exploited, disenfranchised so that those families could be successful.”

Jane Kelsey, who spoke with enough candour to fill the entire room, described the process of the bill as “provocative”, and criticised David Seymour for pushing it. “I believe that it is a political stunt that is about political opportunism,” she said. “The fact that there is this disingenuous approach of the same minister to regulatory responsibility and to Treaty principles suggests that he himself doesn’t have principles.”

The second former Treaty negotiations minister to appear in Room 3, Andrew Little, also spoke against the bill. “The Treaty, if it represents anything, is a recognition of the pre-existing rights and interests of Māori and the protection of those rights,” he said. “And the journey we’ve been on is not only to see the wholesale and egregious breach of those rights over decades and decades but, in the last 50 or so years, the duty of reconciliation and restoration.

“Correcting the wrongs does not create inequality. It restores the situation to what it was or should have been. To deny the ability to uphold the terms of the Treaty would itself be an act of inequality. It would make Treaty rights secondary or inferior to other legal rights and would therefore make them unequal.” Little said Treaty commitments held him accountable for ensuring positive outcomes for Māori, especially as minister of health. “A minister considering their obligations under the Treaty will be thinking about Māori and their health at the time.”

Lawyer Ani Mikaere said she “took heart” from previous opposing speakers. She argued that the Treaty reaffirmed “supreme political authority to tino rangatiratanga of the rangatira” but “delegated kāwanatanga to the Crown so that it could regulate the conduct of British citizens who were living here in Aotearoa.

“The Crown occupies its current position of privilege by virtue of the fact that it has lied, cheated, and infected its way to dominance during the decades immediately following the Treaty of Waitangi,” Mikaere said. “Now, the precise detail of the process by which the Crown acquired dominance may vary from iwi to iwi, from rohe to rohe, but the general pattern remains depressingly constant.”

4pm: ‘I ask the member to leave the room’

Economist Ganesh Nana described the bill as “thoroughly repulsive”. His primary concern was the level of hurt caused to Māori since discussions about the bill began. “This bill is not and should not be treated by this committee as any ordinary bill. It requires more than standard processing. Your task is so much more than that,” he said.

“There must be a formal apology from this House that this repulsive bill ever got introduced in the first place, and there must be consistent and genuine efforts to repair the bridge between Māori and the Crown,” Nana said. “I am waiting for the adults in the room to stand up and take responsibility. Sadly, I find myself asking if there are actually any adults in the room or in the House.”

National MP Rima Nakhle, who had kept silent throughout the entire affair, finally spoke to pose a question to Nana. But it wasn’t a question, nor did it have anything to do with the issue at hand. Instead she asked Nana to explain the current economic state. The comment earned groans from the public seats.

And yet, it wasn’t Nakhle who was eventually reprimanded by Meager. When Nana returned to his seat, a member of the audience performed a mihi to honour his words, telling him, “You were born here, you are tangata whenua.” But after Meager’s repeated requests for silence were ignored, he ordered Room 3 to be emptied.

The audience member let out an exhausted “auē”. A priest in the back row clapped Nana on the back: “That was just so bloody wrong, and says it all.” Meager gave the room a stern warning: we’re on limited time, and no interruptions will be entertained.

Historian Vincent O’Malley, who has published several works on the Treaty, patiently waited to offer his evidence against the bill. He reflected on the Treaty’s role in New Zealand’s national identity. “We look at ourselves in the mirror and what we see reflected back at us has not always been flattering,” he said. “It’s been a difficult, messy and protracted process, but also an essential one for the future of our country. This bill would put at risk the considerable progress that has been made since the 1970s and needs to be rejected.”

Seven hours earlier, Gary Judd had suggested that pre-Treaty Māori could not have had sovereign rights because several tribes were at war throughout the early 1800s. As the day wound down, Tamatha Paul asked O’Malley what he thought of Judd’s argument. “Has he heard about the 100 Years’ War in Europe?” O’Malley quipped.

5.20pm: Private time

The day ended 20 minutes late, probably not as bad as the committee may have feared. There were yawns and stretches as the public filed out of Room 3, but Meager and co. remained glued to their seats – they still had half an hour of private hearings to get through.

January 28, 10am: This post has been updated with extra information and to amend a misattributed comment