Are members of parliament able to say whatever they want in the debating chamber without suffering any consequences? Well, no … but also, sort of yes. Andrew Geddis explains.

Apparently something happened in parliament yesterday, but I blinked and missed it. Catch me up?

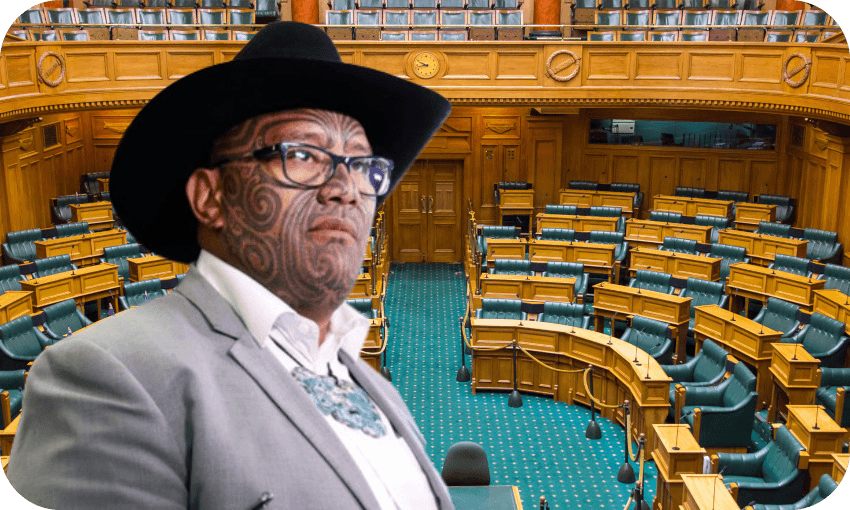

Don’t worry – The Spinoff’s Live Updates always has you covered! In a nutshell, following on from questions by David Seymour to the PM Chris Hipkins, Te Pāti Māori co-leader Rawiri Waititi asked a supplementary question that referred to something Waititi himself said was suppressed by a court.

Hang on – publicly referring to matters suppressed by a court. Isn’t that, you know, a crime?

Yep. Knowingly publishing information in breach of a suppression order can get you locked up in prison for up to six months.

Oh dear. Can Waititi expect a visit from the police some time soon?

No. Because Waititi was asking a question of a minister, he was engaged in a “proceeding in parliament”. And everything said in all such proceedings gets an “absolute privilege”, meaning that evidence of what he said cannot be used in court proceedings to establish any legal liability.

Wait – so even if Waititi committed a crime by asking his question, what he said can’t be used to convict him?

You got it!

That’s a pretty big get out of jail free card!

Only sort of. Because there are other consequences that may flow from his actions. MPs using this free speech privilege to undermine the courts’ business (such as deciding whether to suppress publication of the identity of individuals accused of specific crimes) is A Very Bad Thing. Accordingly, the rules of parliament require that they get specific permission from the Speaker before making reference to matters currently before the courts. Waititi didn’t do this.

Naughty! What does that mean?

Well, under parliament’s own rules, it may be a “contempt” to “knowingly making reference to a matter that is suppressed by an order of a New Zealand court, contrary to the Standing Orders, in any proceedings of the House”. And the House can then itself choose to punish such a contempt.

How does it decide whether or not to do so?

The matter goes to its privileges committee, which by journalistic convention must always be referred to as “powerful”. Basically, it’s made up of senior MPs from all the parties. They then hold a kind of in-house trial, decide if what has happened is a contempt, and then decide what penalty should apply.

How likely is it that Waititi will have to front this committee? And what might happen to him?

It’s almost certain, I’d say. Any MP can complain to the Speaker that a contempt has been committed. This undoubtedly will happen. And if the Speaker accepts the matter is serious enough, he must send it on to the (powerful!) privileges committee. I can’t see any basis on which the Speaker will refuse to do so here, although there simply may not be time for the committee to deal with the issue before parliament is dissolved for the election. Meaning that it might be the next parliament that has to pick the issue back up.

If the (powerful!) privileges committee eventually finds Waititi has committed a contempt, then it effectively decides on the appropriate punishment. This can range from: a censure (formal telling off); a requirement to apologise to the House (as Michael Wood had to do yesterday); a fine of up to $1000; a period of suspension from the House; and even imprisonment for the remaining term of parliament. This last punishment has never been applied in Aotearoa New Zealand, and it won’t be here.

Huh! But there’s still one thing I don’t get.

Just the one thing? Surprising! But, do go on.

If it’s a crime to publish things in breach of a suppression order, how come some people have been sharing what Waititi said in parliament all over the socials?

Because the same legislation – the Parliamentary Privileges Act 2014 – that sets out the absolute privilege enjoyed by those involved in parliamentary proceedings also gives legal protection to anyone who communicates those proceedings to the public. Basically, if all you are doing is saying what happened in parliament, you are granted “an immunity from any civil or criminal liability for the relevant communication.”

So, even if you’re saying what an MP said in parliament is a crime, you can’t be found guilty of it?

Pretty much – unless it can be shown that you “acted in bad faith” or “acted with a predominant motive of ill will.” Which are very high hurdles for anyone bringing charges to get over.

But, equally, if what Waititi said in the House discloses something that the courts have decided ought to be kept out of the public arena then perhaps openly repeating it isn’t such a good idea. Just because we can do something doesn’t mean that we have to do it.