International aid serves a number of purposes beyond helping the world’s poor and vulnerable, and Trump’s decision will have implications for every one of us.

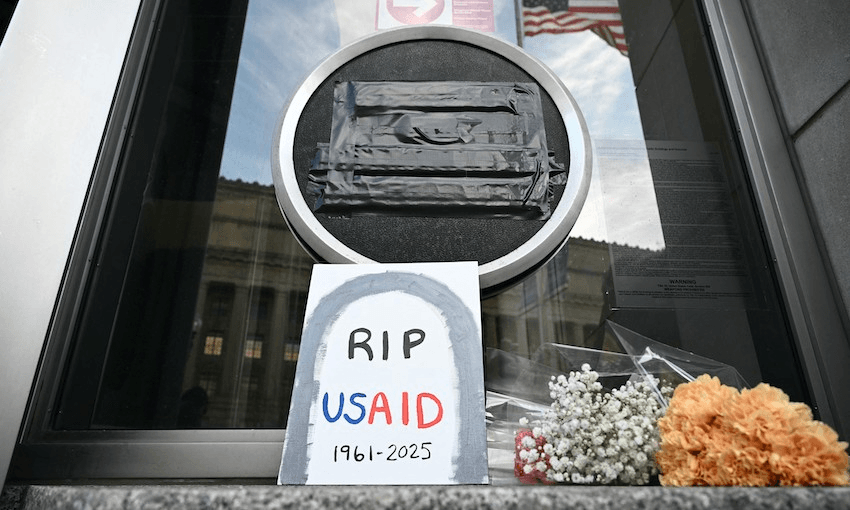

The decision by American president Donald Trump to disestablish the USAID – the world’s largest international aid organisation, with an annual budget of over US$40 billion – with the stroke of a pen is being lamented across the world. Spending on international aid might seem unjustified when many Americans are facing a cost of living crisis, but in reality that $40 billion a year in aid pales in comparison to the almost $900 billion the US spends on defence annually. And it is less than 1% of the federal government’s budget. In short, there are other places where belts could be tightened.

The closure of USAID cuts will undoubtedly hurt millions of people, but some of them may not be the ones you expect. As international development specialists, we identify three groups that will likely suffer as a result of this decision.

The first and most obvious group affected are the millions of recipients of forms of USAID globally. These are among the world’s poorest and most vulnerable. In Afghanistan, for example, where some families are so desperate they will sell a child in order to get some money to feed the rest of the family, the US has contributed more than US$3.7bn in humanitarian aid since the return of the Taliban, much through UN and other international organisations. The freeze on funds could leave nine million people with no access to healthcare and it has already shut down a major midwifery programme – mothers and babies will die.

We are sickened and appalled at the hypocrisy in the world’s richest man freezing international aid flows from the world’s largest economy to millions of the world’s most vulnerable and poorest. This is what Elon Musk, Donald Trump’s austerity hatchet man, has done, shuttering the doors and the accounts of USAID, recalling all of its overseas employees, escorting more than 60 senior staff off the premises and sending thousands of its employees home on leave. USAID money contributes about a fifth to all of global development programmes that uplift or protect basic food, shelter, health and education of the world’s poorest families.

Aside from Musk’s more outlandish and hysterical claims about USAID being a “criminal organisation” (it is clearly not), “rotten to the core”, and that it supports terrorism (no, although the case of Afghanistan is complex), we could certainly list weaknesses and inefficiencies of USAID – as we could for any large aid programmes. The White House’s cherry-picked list of projects and programmes it objects to (while stunningly incorrect in several cases) still amounted to less than 0.01% of the USAID budget. But despite claims to the contrary, no large-scale abuse or fraud has been unearthed to date. Thus we suggest care is needed before “throwing out the baby/ies) with the bathwater”.

USAID does a huge amount of good globally through thousands of projects, large and small. There has been an immediate stop to some very good programmes in our region, from funding to build adaptive capacity for climate change, and the training and livelihood support for poultry farmers in the Eastern Highlands province of Papua New Guinea. In health there has been significant work across the Pacific with TB, malaria and HIV health programmes, and a polio vaccination programme in PNG that has immunised 3.1 million children and got on top of a major outbreak of the disease.

The disestablishment of USAID is, as the American journalist Nicholas Kristof summarised pointedly, a case of “the world’s richest men take on the world’s poorest children”.

A second group that will be hurting are American citizens who have lost aid-related jobs and business. Tens of thousands of US citizens work as aid professionals, contractors or suppliers to USAID and its many programmes. The largest amount of donor funds are typically spent “at home”. In the US’s case, one estimate by a congressional research report was that two-thirds of US foreign assistance funds in 2018 were expended on US-based entities. Their generous donations of food aid to the World Food Programme come from purchasing vast quantities of grain from the Midwest: in 2024 the USAID spent $70m on commodities from Minnesota vendors alone. As the Washington Post headline put it, “Gutting USAID threatens billions of dollars for US farms, businesses”.

Our third identified group is… everyone else, including you! International aid serves a number of purposes beyond helping the world’s poor and vulnerable, and humanitarian support after natural disasters. Aid is an important source of “soft diplomacy” for donor countries. Among Pacific Island states, USAID had been ramping up its efforts to counter what the Biden regime saw as the significant threat of Chinese influence extending and deepening across the region. Aid funding has been used to counter China’s growing influence globally. Geopolitics has always shaped the focus and direction of international aid – it is never purely about helping the poor and most vulnerable – and to drop the ball in such a spectacular fashion has strategically opened up opportunity for others in various parts of the world, as well as increasing the need for defence spending. This potentially heightens the prospects for “hard diplomacy” and conflict such as we have seen in Ukraine and Gaza.

Linked to this, the decision to eliminate a government agency by executive order undermines the rule of law in the United States, which in turn reduces the credibility of the US in international eyes. If the US can arbitrarily and immediately rip up bilateral contracts and agreements with countries, then so surely can these partner countries? This follows on from other Trump-instigated withdrawals of global agreements and arrangements – the Paris climate accord and the WHO – and taken together, we lose any sense of security that comes from an already eroding “global compact”.

And, finally, international aid connects us with the world. A former USAID director noted, “For much of the world population … the work of USAID makes up the primary (and often only) contact with the United States.” Aid is relational, it builds, works off and succeeds because of relationships as an enduring two-way thing, not as a momentary, monetary one-way transaction. Through aid programmes and the hundreds of thousands of people working in the aid sector, people in the US – and in Aotearoa New Zealand – are connected to people in Panama and Samoa. We learn about each other’s perspectives. We are part of the humanitarian project that believes in doing our part to alleviate suffering and maintain human dignity. Aid helps us turn to each other as global neighbours, knowing who to approach and how to approach each other, especially when we need to talk to our neighbours. Such as when we worry about access to the Panama Canal, or when we feel embarrassed about running a navy ship aground in someone’s backyard.

If the aid budget is cut back in the world’s richest countries, we become ignorant of other communities’ lives. And if we do not want to know how our neighbours live and feel, we also become insignificant in their eyes.