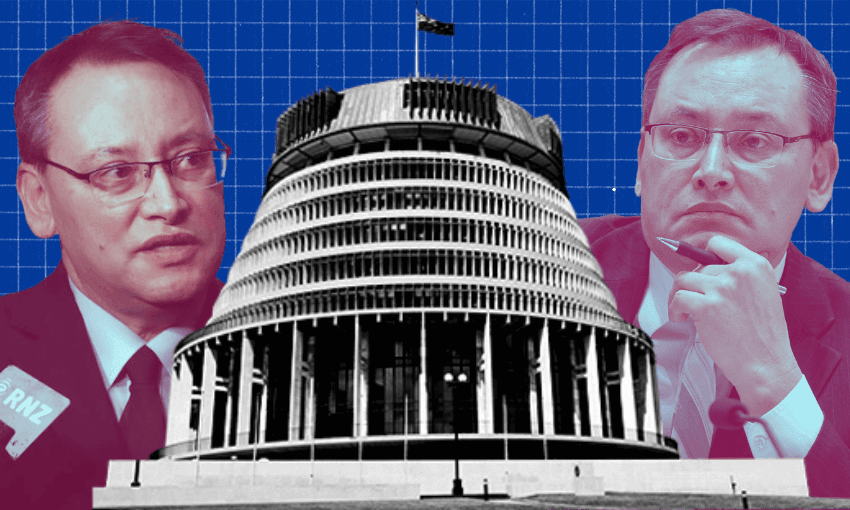

Shane Reti’s demotion is a reminder that the best experience for being a minister is being a minister, writes Henry Cooke.

First published in Henry Cooke’s politics newsletter, Museum Street.

Shane Reti – or “Doctor Shane”, as Judith Collins would always call him – is a lovely man.

The first time we had a proper interview he spent about 10 minutes explaining his mission to build a Hundertwasser Art Centre in Whangārei, which had nothing at all to do with the story I was there to talk about, and then whipped out a whiteboard to explain the interview subject. I forget the details of the story itself, but I remember his manner easily endearing him to me, as one would expect of any decent GP.

But a good bedside manner does not make you a good minister. And experience within a field does not necessarily make you well-suited to run it.

Reti was demoted out of the health portfolio and kitchen cabinet by Christopher Luxon today, amid some very poor polling for National and widespread reports that the healthcare system is not in fact able to save much money without any cuts impacting frontline services. Whether the problems in health can really be placed on Reti’s door is not an easy question to answer: he’s not the one holding the purse strings, or the one who created an integrated jobs market with the richer country of Australia, or responsible for the fact that our population is getting older, and new ways of helping them do so at greater comfort cost a lot of money.

Then, it is hard to say that there is nothing Reti could have done better. He has not exuded ministerial confidence. He has not managed to get much of the sector onside, or paint a compelling vision of where it is going. And he is surely somewhat culpable in the Pharmac debacle at the last budget – which saw his finance minister eventually forced to spend $604m of this year’s budget last year, twice what she had committed in the election campaign.

Reti’s fall can seem surprising given his successful career on the pointy end of the health system as a GP in a deprived area. Shouldn’t that experience have made him just the man to shepherd through National’s programme here? Well, no.

The first problem is with the specifics of the Reti case. Being a good GP involves being good at medicine and at running a small business. These skills may well be useful for being a minister of health, but they are not directly related in the way you might think. Knowing how to take someone’s blood pressure (I know I know, it’s much more than that) is not particularly useful when you are managing a budget in the tens of billions of dollars and the union boss across from you is threatening to strike, or indeed, your old peak body is demanding more money. The problem is one of scale: as a GP it is normal to spend a lot of time caring for a single family, as minister you have to allocate resources so that the health of five million New Zealanders is looked after.

(There is also a very small country tension you get from actually knowing people in the sector you have to regulate. You could well have to declare so many conflicts of interest that you lose a lot of crucial “delegations” – roles, essentially – to your associate. Or of course you risk a corruption allegation.)

The second problem, and I think the real core of the matter, is that past careers have a very limited value as a frame for political analysis.

Sometimes, they are the main recommendation for a new MP on their way to power – did you know this guy used to run Air NZ? More often they are whipped out only in the negative as a boring partisan attack on MPs whose main job before politics was other politics, such as the absurd attacks on Jacinda Ardern’s teenage job at a fish and chip store.

But really, a career largely in politics can lead to you being an incredibly successful politician. Helen Clark and Bill English spent most of their professional lives as politicians before becoming prime minister, with English doing a stint at Treasury and Clark working as as lecturer in their 20s before election to parliament at the dawn of their 30s. They were both incredibly consequential and successful politicians.

You could say the same about Chris Bishop, who worked for politicians and then as a lobbyist before entering parliament, or Chris Hipkins, etc etc etc. The list of successful politicians who have never done much not related to politics is long and bipartisan, and can be extended to world-changing politicians like FDR.

This shouldn’t be surprising – getting things done in Wellington is complicated. If you’ve been up close to others doing it for many years you will probably be better at it than someone whose only experience of government is adversarial.

Conversely, there are plenty of people whose past careers do seem to have set them up well for the job of running a country or ministry. Dwight D Eisenhower’s experience as the supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe during the second world war was undoubtedly crucial to his successful presidency. John Key’s massive success in business set him up for massive success in politics. And it is clear that being a natural performer was crucial to the electoral success of Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump.

There are also people with impressive success outside of politics who can’t really make it happen inside it, such as David Shearer. And there are people who have only ever worked in politics or Government who really do falter once they have a sniff of power – like Jami-Lee Ross. I am not sure there is really a particularly meaningful pattern one can draw here.

Politics is a skill in and of itself and most people don’t know if they are any good at it until they actually try. Subject matter expertise is certainly of great use, but a good minister doesn’t need to be down in the details, and if they are they may waste their precious time there. This doesn’t mean they should just outsource their brains to their policy officials, but they should be comfortable with knowing that some limit on their knowledge of the minutiae is sensible. Being comfortable with this, yet also being comfortable enough with your brief that you can engage in the really big questions, argue your side in Cabinet, swot down the Opposition in Question Time, and have a long back and fourth with a journalist, is the meat of being a good minister. I don’t think there is any “profession” that really lends itself to this.

And yet, when writing about politicians one needs some content to work with. And since most maiden speeches are anodyne and most modern MPs are terrified of saying anything interesting to a journalist about their beliefs, we naturally circle back to their former careers as something to pick over and analyse. It probably does matter. Just a lot less than you might think.