With dozens of Māori seats up for referendum, this year’s local elections will reveal where Aotearoa truly stands on representation.

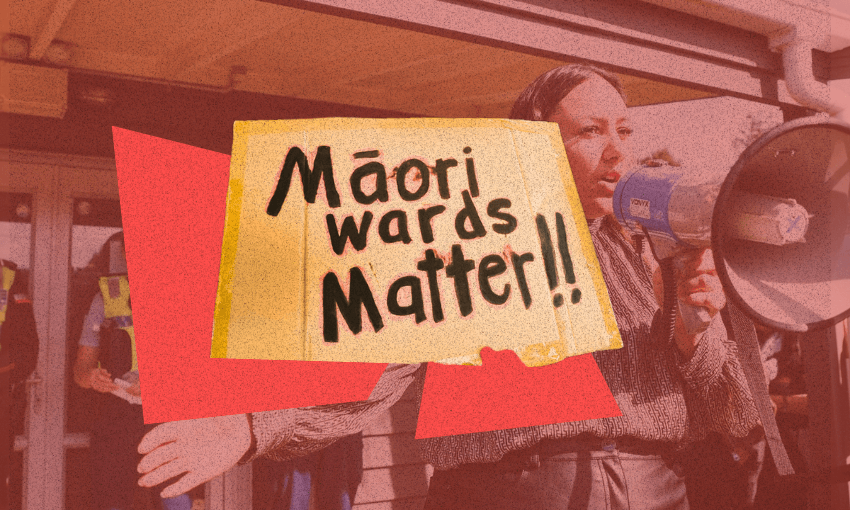

Last year, the government introduced legislation requiring all local authorities that had established Māori wards and constituencies to hold a referendum on these seats during this year’s local government elections. The policy, which faced strong opposition from councils and Māori communities, has resulted in a total of 42 authorities set to hold a referendum on Māori wards in October.

The cost of these referendums is estimated to exceed $2 million, with the Greater Wellington Regional Council alone projecting costs of $350,000. This financial burden, coupled with the likelihood of anti-Māori representation outcomes, has fuelled frustration among advocates of Māori representation.

The move reverses a Labour government policy that had removed citizen-initiated binding referendums on Māori wards. Critics see this shift as a blow to Māori wards, given the anticipated majority opposition in October’s votes. The challenge for them now lies in mobilising enough public support to retain these wards through the ballot box in local elections with notoriously low voter turnout.

In a December High Court ruling, Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Whātua’s appeal against Kaipara District Council’s decision to abolish its Māori ward was dismissed. Among New Zealand’s 78 councils, only Kaipara District Council and Upper Hutt City Council opted to disestablish Māori wards. Councils that established wards through votes were not required to hold referendums, and others, like the Far North District Council, continue to explore the ramifications of avoiding a public vote.

Six months ago, I wrote about the evolution of Māori activism, emphasising the need for collective efforts beyond hīkoi and grassroots protests. Late last year, one of the largest ever hīkoi to parliament took place, opposing perceived anti-Māori policies. The movement led to a record number of submissions on the Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Bill – which is apparently “dead in the water” – and a surge in Māori voter registrations. Over 3,000 people enrolled on the Māori electoral roll during the hīkoi, driven by calls from prominent Māori leaders.

Stats NZ data from June 2023 compiled by the Local Government Commission indicates that if all eligible Māori voters registered on the Māori roll, and all local authorities had Māori wards, there could be 113 Māori seats across local authorities, which would make up approximately 13% of all council seats. With the growth in the Māori electoral population in the year and a half since, that number is now likely to be even higher. However, civic engagement remains a challenge. Despite growing awareness, voter turnout at local elections has steadily declined in recent years.

In the last general election, total voter turnout was 78.2%, down from 82.2% in 2020. Turnout for Māori voters on both the general and Māori rolls was 70.3%, slightly lower than the 72.9% in 2020. Yet, young Māori voters defied the trend. Turnout among 18 to 24-year-old Māori rose to 70.3%, marking a significant increase over previous years.

In 2023, parliament published an inquiry into the 2022 Local Elections, with low voter turnout being a primary focus. A statistical analysis conducted by Auckland Council found that those who identified as being of Māori descent when enrolling were less likely to vote than those of non-Māori descent, with 25% of Māori likely to vote vs 39% of non-Māori. In 1989, there was an average turnout of 60% across all local authorities. By 2022, that average had decreased to 42%. The inquiry made a number of recommendations to improve a range of areas like resources, processes and even trials for online and electronic voting. The aim was to implement key changes before this year’s local elections.

The referendums on Māori seats are about more than local governance; their outcomes will shape the trajectory of representation and inclusivity in New Zealand for years to come. They serve as a barometer for the country’s evolving views on equity and partnership under Te Tiriti o Waitangi. A vote to remove the wards would signal a retreat from efforts to uplift underrepresented voices, while a result that keeps them could bolster momentum for broader structural change. As voters cast their ballots, the implications of their decisions will ripple beyond local councils, influencing debates on national identity and governance in ways that will be felt for generations.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.