Proposed changes to the Fisheries Act 1996 could see on-board cameras, introduced to protect endangered marine and seabird species, shut off from public view. Lyric Waiwiri-Smith explains.

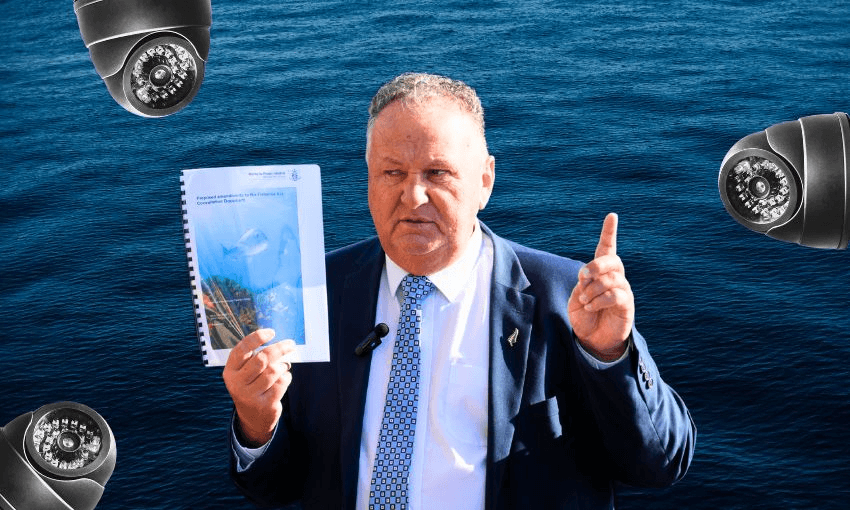

Minister for oceans and fisheries Shane Jones was in his element on Wellington’s waterfront on Wednesday morning. While waves crashed onto the rocks down Lady Elizabeth Lane and seagulls squawked overhead, the NZ First minister announced plans for a revamped Fisheries Act 1996, with the official line that proposed reforms to the bill would see the removal of “unnecessary regulations that impede productivity”, which will help the country “fight its way back to economic prosperity”.

Jones dubbed the proposed fisheries reforms, which include major changes to the Quota Management System, the most significant in decades. Though cutting red tape and rebuilding a “nah, yeah” economy rather than a “yeah, nah” economy has been a major focus of the coalition government this year, one proposed change, highlighted by Jones, was less expected: footage captured on commercial fishing vessels could become ineligible for release under the Official Information Act.

A new consultation document sets out “Options for enhanced protections to provide certainty for fishers in terms of privacy and commercial sensitivity of camera footage”. One of the options is to stick with the status quo, which already allows the Ministry of Primary Industries (MPI) to withhold footage under various sections of the OIA, but MPI would “confirm our practices for assessing requests for camera footage with the Ombudsman”. The second is to “remove the ability for requesters to use the OIA to ask for footage collected from on-board cameras”, which would require an amendment to the Fisheries Act.

Jones said the final decision would be Cabinet’s, but made it clear that exempting the footage from the OIA was his preference.

So … Do we really need to see some blurry fish videos?

Desperately lodging Official Information Act requests to check footage across hundreds of commercial fishing boats is definitely not how most New Zealanders are spending their time, despite Jones’ reckons the industry is now at risk of being “charged on TikTok” for its fishing practices. Though most of us will likely never request this footage specifically, Jones said he hoped exempting it from the Official Information Act would stop it from falling “into the hands or onto the laps of people that, in my experience, hope to do damage to this valuable industry”. The fishing industry has long expressed concerns over the public being able to access the footage via the OIA, warning that the material “could be reduced down to a collection of stark instances to create a distorted and misleading picture of the seafood industry”.

Capturing video on commercial fishing boats has grown around the world in recent years in line with concerns around fishing sustainability – the aim is to monitor illegal fish dumping and bycatch of endangered species. Regulations brought in by the National government in 2017 specified that certain fishing vessels should have electronic monitoring equipment (including cameras), with the footage captured to be provided to MPI, but implementation was deferred. It was then postponed by new fisheries minister Stuart Nash when the Labour-NZ First government came in in 2017 (Nash shortly after rejected an official request from the industry to exempt footage from the OIA). The rollout was delayed again in 2019, before certain vessels in areas where Māui dolphins were at highest risk were finally equipped with cameras later that year. A wider rollout was promised during the 2020 election campaign and began in 2022.

Jones, as minister of fisheries in the National-NZ First-Act government, announced a review of the rollout in February 2024, but it eventually resumed in September, albeit with fewer rules and reduced costs. As reported by Stuff, 158 inshore fishing vessels are now equipped with cameras, with another 100 or so to be completed by May this year, which MPI says will cover around 85% of the total catch by volume of inshore fisheries in New Zealand.

Though the Labour government had considered deep-sea trawlers (including those used specifically for catching scampi) as the next round of vessels to be fitted, Jones told Newsroom the government had no plans to see this out.

Self-described as “no fan of cameras”, Jones has regularly voiced his disapproval, but was met with pushback from both Cabinet and those within the fishing sector during the review for the rollout.

Footage is intended to provide further evidence, alongside commercial fishers’ reports of bycatch and fish that is sent to MPI, but Jones said the industry should not be “charged in the court of public opinion”. “Does the public have a right to know what’s happening in every cow shed tonight? Does the public have a right to know what’s happening on every egg farm? Does the public have a right to know what’s happening in your home? No, they don’t,” he said. “I do not accept state surveillance of industry.”

What do the cameras actually show?

Their greatest worth is not necessarily in revealing anything egregious, but rather that their presence encourages more honest reporting from fishers. In April 2024, the Ministry for Primary Industries released an overview of data collected from 123 vessels fitted with cameras. Compared to reporting from before cameras were installed, there had been a 3.5-times increase in reports of albatross interactions (which Newsroom reports means mostly deaths), a 6.8-times increase in reports of dolphin captures, a 34% increase in the number of fish species reported in a catch, a 2.1-times increase in the number of fish species reported in discards, and a 46% increase in the reported volume of fish discards.

The cameras can influence policy change too. In June, Fisheries New Zealand introduced new rules for commercial fishers using surface longline methods – the use of special hook shielding devices, or the use of tori lines, line weighting and gear setting at nighttime – to avoid catching protected seabirds. The change was spurred by scientific modelling, public feedback and a review of the on-board camera programme. Fisheries management director Emma Taylor told RNZ the cameras “provide independent verification of fishing activity, including accidental bycatch of protected species”.

The reforms to the Fisheries Act 1996 also come as the Department of Conservation prepares its next survey of the Māui dolphin population. The last survey, taken in 2021, found only 54 Māui dolphins over a year old left worldwide.

What does the industry think?

Iwi-owned fishery Moana New Zealand has had cameras installed on all of its vessels for nearly a decade. Its inshore general manager, Mark Ngata, said cameras were integral for capturing accurate data to inform sustainability decisions and keep Moana NZ’s status as a “good kaitiaki” in the sector. One of the sustainability resolutions Moana NZ has committed to since 2016 is the protection of Māui dolphins, in partnership with seafood giant Sanford, by removing net fishing in Māui habitats and requiring all fishing methods since 2022 to be Māui-safe.

Ngata said having cameras on vessels had given his customers and the public “some surety and certainty” about the fishery’s practices, but admitted the company had heard concerns regarding lack of privacy around the cameras. “Our fishers are out at sea, as with the other gents, anywhere from two days to a week,” Ngata said. “We feel the privacy of the fishers, and the information that we get is important, but MPI has full access to it.” He agreed with Jones that a regulator should be able to determine whether the public should be able to access this information too.

Seafood New Zealand chief executive Lisa Futschek said the proposals were “absolutely positive for everybody” and “all about sustainability”. She highlighted the proposed reformed law’s potential for economic growth, though this must be “ensuring sustainability is maintained, and nothing about that changes through these proposals”. She argued this is shown through the proposal to allow vessels that have cameras or observers on board to return over-quota fish to the ocean rather than being brought to landfill. The proposals do not mention any changes to the legality of high grading, the practice of discarding low-value fish in favour of more valuable fish.

What do the critics say?

The threat to transparency of the OIA proposal was a key theme, with WWF-New Zealand’s Kayla Kingdon-Bebb telling The Post, “Greater transparency and accuracy in the reporting of protected species bycatch and non-target discards is incredibly important to ensure the sustainability of our marine resources now and into the future.” Added LegaSea’s Sam Woolford, “Cameras on boats have shown 46% more discards than what was previously being reported. How can we take this proposal to limit transparency seriously?:

Where to from here, captain?

With the full consultation document now available to the public, the government is seeking feedback on the proposed reforms, which will close at 5pm on March 28. “I know that it’s a consultation process and there’ll be a variety of views that eventually we’ll have to take account of as a Cabinet,” Jones said. “My expectation is that legislation will be passed before the next election.”