Could iwi and hapū be the unexpected solution to the government’s asset dilemma?

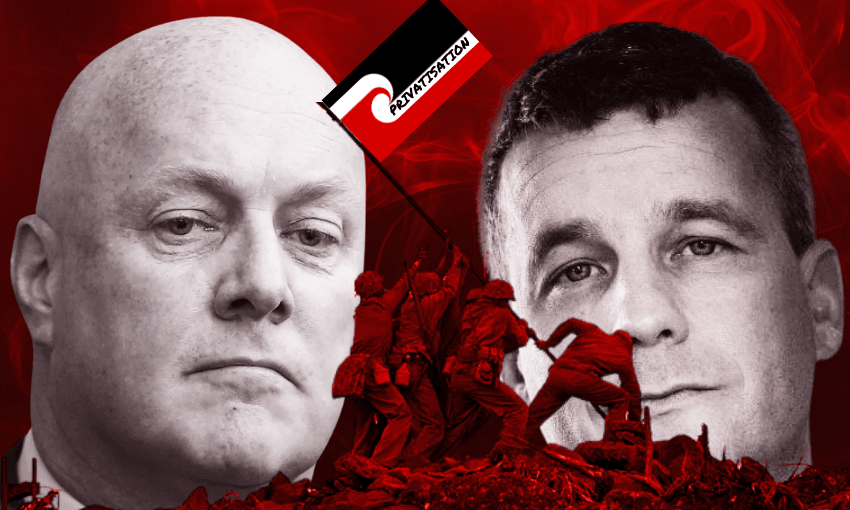

David Seymour pressured the prime minister into an unwelcome conversation, and in the couple of weeks since the Act leader raised the issue in his state of the nation speech, privatisation has shifted from absent in the growth agenda to “open for discussion” long term, to the Treasury now reportedly reviewing state assets and management options.

Former prime minister John Key waded into the conversation, saying there was “not a hell of a lot to sell”. This is, of course, is against the backdrop that in 2013, Key’s government sold 49% of the Crown’s holdings in power companies Meridian Energy, Genesis and Mighty River Power (now Mercury) to investors. But as NZ Herald’s Claire Trevett put it, “[Key] had the political capital to do it and he took the time to do it. Luxon has time but does not have the same capital.”

Which turns us to the unashamed politics of this discussion. While the soon-to-be deputy prime minister has forced the prime minister’s hand, the current deputy prime minister, Winston Peters, is proudly reaffirming that he has spent his whole political career “ensuring that our assets stay in our possession”. NZ First’s enduring view is that state-owned assets belong to all New Zealanders.

So what is a prime minister to do?

Despite being thrust into a conversation that doesn’t seem like a high priority, the privatisation debate presents National a unique opportunity to pacify both coalition parties while upholding a commitment to its own values of limited government and recognition of the Treaty of Waitangi as the founding document of New Zealand.

In a serious conversation about privatisation of state-owned assets that are retained onshore, there is no better partner for the Crown than the partner it already has – iwi/hapū Māori. If Act is serious about privatisation, then it needn’t look further than its leader’s own iwi, Ngāpuhi.

The government has already made clear that reaching a settlement with Ngāpuhi is a high priority, but the form of that settlement is likely to be a challenge. In October, Te Rau Allen-Arena, chair of Ngāpuhi hapū Te Whiu, told Treaty negotiations minister Paul Goldsmith that Ngāpuhi should get $8.43bn in redress. For a government that slashed $3.9bn of government expenditure in its first year, with savings estimated to be $23bn over four years, cash compensation of that size is an improbability of the highest order – even before you consider the need for relativity across settlements.

Instead, Seymour’s apparent insatiable lust for a conversation on privatisation has had the unintended consequence of elucidating the need for the Crown to place greater assets on the table when working towards settlement with Ngāpuhi.

Former Treaty negotiations minister Christopher Finlayson has said that sometimes he needed to push the boundaries in Treaty settlements when dealing with natural resources. I say the time has come for National to be bold once again.

Tupu Tonu to one side, there are ample assets in the north that the Crown could divest from, helping to reach a settlement that goes much further than cash.

Take Northpower Fibre Limited. The Crown has a single shareholding in the organisation, because it was established as a local fibre company by virtue of the government-led ultra-fast broadband programme. There is no denying this public-private partnership has been an overwhelming success, and with Ngāpuhi and Northpower sharing geographical interests, we have a prime example of where privatisation could be used for mutual benefit.

Another example is NorthTec, which is currently a business division of Te Pūkenga. The government has already said it is supporting the return of vocational education decision-making to the regions by amending the Education and Training Act 2020 to disestablish Te Pūkenga, and will support technology and polytechnics to be established as autonomous entities. Carving a place for NorthTec to be a joint venture between the Crown and Ngāpuhi as part of the Treaty settlement could help ensure Te Tai Tokerau grows the skills that iwi and hapū leaders already know they need.

Or take the government’s recently released minerals strategy, which identifies three minerals of potential in the north: gold, sulphur and lithium. Toitū Te Whenua manages over two million hectares of land on behalf of the Crown. It makes sense that where economic opportunity relating to mineral production exists in land in the north that is currently under stewardship of the Crown, a right of first refusal (in the absence of returning that land) for permits and consents could be made to Ngāpuhi.

It takes zero political will to sell an asset to the highest bidder, but it takes enormous circumspection to entertain privatisation through the lens of penance for one’s own goal – the Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Bill.

For a prime minister with a penchant for a good “turnaround”, what better turnaround of Māori and Crown relations than being the prime minister who dared to set a course for productive asset privatisation through iwi/hapū Māori?

After all, if devolution is a government priority, there is nothing more devolved than returning parts of the Crown’s asset base to those whose suffering helped build the asset base in the first place.