We dust off the abacus.

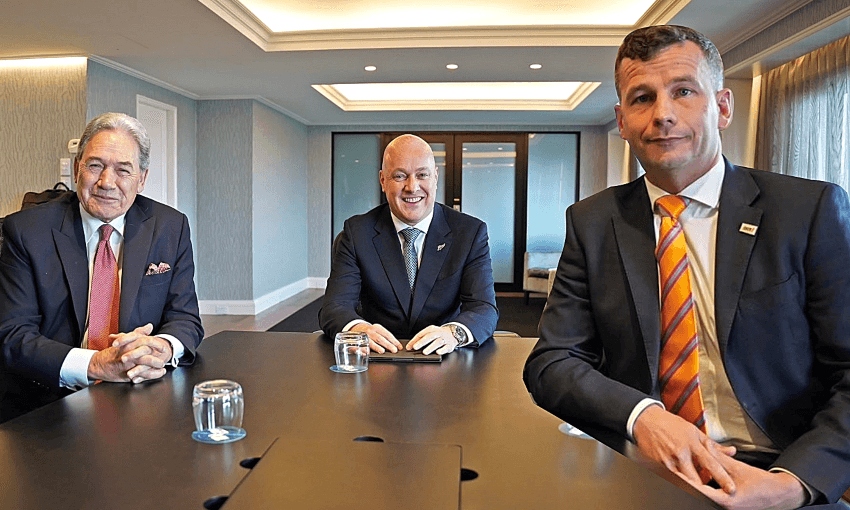

There was a bit of throat clearing and chest thumping about the leader interviews to mark last week’s first birthday of the first fully fledged three-party coalition government in New Zealand. Among them was David Seymour, who told RNZ: “I think we’ve made a disproportionate contribution to policies of the government.”

Is he right? It depends, of course, how you cut it. Sadly, we have no transcripts of the discussions in cabinet from which to judge who is bossing the room. The broad assessment of pundits has been: yes, they probably did. But can we find any numbers that bear that out? Let’s do what we can.

The first thing to say is that, together, the three parties in the coalition collected 52.8% of votes cast. Of that governing total, if we’re to be brutally proportionate for a moment, it would look, rounded to the nearest percentage point, like this:

♦ National 72%

♦ Act 16%

♦ NZ First 12%

Of course, proportional government does not mean proportional clout, evidenced most obviously in the percentage support of the opposition parties largely vanishing in a puff of loserness.

And just as it does not translate neatly to coalition deals, nor does it translate neatly to the ministerial roles within the executive. There are 30 ministers, and if we assign those inside cabinet a point and those outside half a point, the distribution looks like this:

♦ National 16.5 or 66%

♦ Act 4.5 or 18%

♦ NZ First 4 or 16%

Pretty close to the numbers above, but another imperfect measure. The two most powerful members of the executive are the prime minister and the finance minister, both roles held by National MPs. A better metric might involve counting the various portfolios, assessing the relative influence of all those portfolios and adding again, but not today, sorry.

The evidence to which Seymour points is the quarterly plans. “If you look at these quarterly plans, often half the ideas come from the party that has only one sixth of the MPs in the government,” he told RNZ (and the Post).

When the most recent quarterly plan emerged in September, Act boasted that “of the 43 actions listed, 22 are led by Act ministers, advance Act coalition commitments, or reflect Act policies”. You only have to go as far as the first examples listed, however – the RMA reform bills – to see that many can equally be claimed by other parties. National campaigned on reforming the Resource Management Act. Changing the legislation was in the coalition deals with both Act and New Zealand First.

As far as the work programme is concerned, we can also pull up the spreadsheet that tells us the progress of legislation for the 54th parliament of New Zealand. To date 109 government bills have been introduced – or were in the last parliament and have been reinstated. Each bill has a minister in charge, and this is how they break down according to party stripe:

♦ National 87 or 80%

♦ Act 15 or 14%

♦ NZ First 7 or 6%

Again, we can only draw so much from this. When you have the finance minister, justice minister and leader of the house on your team, that’s going to distort things a bit. And some bills, needless to say, are massively more consequential than other bills. Still, a compellingly disproportionate result for Team Luxon. (If you count only the bills that have been passed into law, it’s National 37, Act 8 and NZ First 3. Act’s result improves to 17%.)

How about impact in the media? The tools at my disposal, and the generic qualities of the party names, mean the best proxy is the leaders.

Google News tells me that New Zealand domain-based news sites have over the last 12 months included the name Christopher (or Chris) Luxon 30,300 times, David Seymour 24,600 times and Winston Peters trails back on 10,500.

Expressed as a percentage of the total, we get:

♦ Luxon 46%

♦ Seymour 38%

♦ Peters 16%

Google News is a big old soup of stuff, mind you. What if we defer to the public broadcasters, and jump on the RNZ search engine? Very different results, it turns out, with Luxon mentioned in 1,550 stories, Peters 734 and Seymour 653.

♦ Luxon 52%

♦ Seymour 22%

♦ Peters 25%

Finally, what and who are piquing people’s interest?

On the chart above, blue is National, yellow is Act and red is – apologies to all – NZ First. Google Trends measures search activity, counts the peak of search as “100” (in this case the first flush of the coalition being secured) and measures the rest as a proportion of that peak. The average rating for the three parties, transposed into a percentage, is as follows:

♦ National 54%

♦ Act 30%

♦ NZ First 17%

As a measure of visibility, if nothing else, that doesn’t feel a mile off. (Note: the numbers sometimes don’t add to 100 owing to rounding.)

If we perform the same exercise but for the leaders, meanwhile, it looks a little different.

For which the average search interest extrapolates to:

♦ National 48%

♦ Act 30%

♦ NZ First 21%

That dramatic yellow spike around November, of course, reflects David Seymour’s introduction to the house of the Treaty principles bill, and the vociferous response that prompted, including hīkoi and haka.

On one hand, a bill that has been pronounced dead by the prime minister can hardly count towards influence in policy. On the other, Seymour insists that even if it is binned next year, it will move his argument forward. Which leaves us with a hackneyed but inescapable answer to the question of the headline: only time will tell.

Did I overlook other available non-pundit-based numbers to measure influence? Let me know.