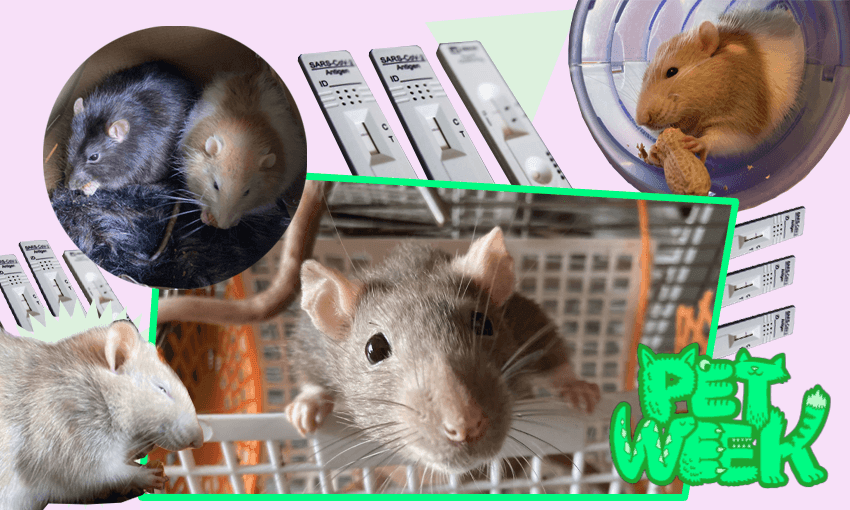

Pet Week: Everyone is talking about the demand for RATs, but nobody is talking about the demand for rats. Alex Casey investigates.

All week we are examining and celebrating our relationship with animals in Aotearoa. Click here for more Pet Week content.

They’re not so different, rat parties and human parties. As the festivities wear on, the more aggro lads start to swing punches at each other, teeth chattering in rage. A spaced-out loner sits in the corner, eyes boggling out of his head while he nibbles on Burger King hash bites. There’s a sudden and tremendous clang – the girls have just smashed a bowl of snacks onto the floor. “It’s not a party until something gets broken, right?” says the chaperone, tidying up behind them.

Although some may recoil at the idea of a room crawling with domesticated rats, Belinda Clarke, owner of A Rat’s Tail rattery and the host of this particular West Auckland rat party, tells me there are over 180 people across the country currently on her waiting list to adopt one of her rats. And she’s relatively new to the rat breeding scene – a more established Auckland rattery has over 500 people in line, clamouring for a domesticated rodent of their own.

Why the demand? Like most things, it comes down to Covid. “There was quite a big jump in the waitlist for rats during the last couple of lockdowns,” Clarke explains. “I think people were looking for pet companions and when the SPCA is all out and you can’t find any dogs or cats, people started to turn to rats.” She describes her rats as “mini dogs” – when she comes home from work she is greeted by her mischief (the collective noun for rats) rattling the sides of their cages and begging to be released for pats.

There’s an even simpler, and much funnier, explanation for the uptick in rat interest: Google. More New Zealanders than ever are searching “buy rats” and getting redirected to boutique ratteries while on the hunt for rapid antigen tests. “For sure they [RATs] have had an impact,” says Clarke. “I’ve had a 50% jump in site traffic in the past month. There must be some people out there looking up rapid antigen tests and going ‘oh, look at these cute rats’!”

The rat vs RAT confusion is one that Clarke has fallen victim to herself. In the very early stages of the RAT rollout in New Zealand, before the acronym was widely known, Clarke and her fellow rat breeders were delighted to see a job advertised for a role in rat distribution. “But at the bottom of the advert it said ‘please be advised, you will not be working with animal rats’ and we were quite disappointed,” she recalls. “A couple of us had been considering it as a real job.”

Clarke has been breeding rats for two years – she took her first pair down to Hamilton to stay with her parents for the first lockdown – and is a part of the New Zealand Registered Rat Breeders Association. “It is essentially a group of breeders that work together towards providing ethically bred rats with great health and temperament, just because we want to avoid backyard breeding and inbreeding as much as possible.” They have tracked their rats for generations, recently assembling a giant family tree dating all the way back to 2008.

A new litter arrives every two months or so, and Clarke is very particular about who breeds and when. Females are bred between six to 12 months, and males are bred at over 18 months to allow them time to be monitored for any issues. Then, the chosen couple will go on a “special holiday” together for two weeks, not unlike two contestants on Married at First Sight. Otherwise, boys and girls must be kept separate at all times. “The boys have pretty big rockets,” Clarke’s partner mutters from the fringes of the rat party. “They only have to mount for like two seconds.”

Clarke then cradles two squirming bright pink rat babies from her latest litter, only three days old, in the palm of her hand. They look like something out of Wellington Paranormal, making almost imperceptible squeaking sounds from indiscernible mouths, eyes still welded shut. The mother rat cautiously approaches the opening of the cage and tenderly lifts them out of Clarke’s hand with her teeth, carrying them back one by one to the rest of the litter.

As involved as it is, rat breeding doesn’t pay the bills. Clarke still works part-time at an indoor airsoft field, where players participate in simulated military action, and spends the rest of the time working on diversifying her rat business, including making rat treats and rat enrichment toys. Sharing a home with another breeder, she predicts there are over 100 rats residing in their garage. But this is no slum: think imported three storey cages featuring luxury bamboo groves, each decorated with repurposed office supplies and homewares for their residents to explore. One rat snoozed in the “in” of an “in out tray”.

The rat parties – where a large group of rats are set free in a row of trestle tables to socialise – are a regular highlight. The rats swing from hammocks, do puzzles, explore tubes, and forage through pine cones for treats. Clarke brings out some peanuts, still in their shell, to demonstrate the dexterity of Cheese, one her prized rats. He holds the peanut in his tiny rat hands like he is praying, and then goes to town with his tiny teeth. She hands me a very fluffy white rat named Odin who is noshing on a Burger King hash bite with both hands. I feel an instant connection.

“Most rats you see on TV and movies will be quite ugly, but Odin is pretty much just a cloud of fluff and he has the cutest little face and he loves cuddles,” says Clarke. But rats like Odin – with white hair and pink eyes – often come with negative connotations. “Lab rats”, Clarke explains. “People generally don’t like pink-eyed whites – there’s a stigma that they are evil, or that they are inbred.” Her fellow breeder, Caitlin from White Rose, picks up one of her own white rats and gives it a kiss. “I love you anyway, I don’t care if you have pink eyes, I still think you are pretty.”

It is also a fact that wild rats are considered pests in New Zealand and, just down the road in Titirangi, have been terrorising Clarke’s neighbourhood for years. But Clarke has nothing to do with this unruly bunch – they are Rattus rattus and she breeds Rattus norvegicus, or fancy rats. “I don’t think people realise that what we are breeding is technically a different species – a wild rat cannot mate with a domesticated rat,” she says. Her rats stay in their cages and have absolutely no interest in going outside. If they are put on the ground, they will beg to be picked back up. They would much rather sit on her shoulder while she does the dishes or watch TV on the couch.

“Unfortunately throughout the years with rats being part of the plague, people think they are just disgusting and don’t realise how great companions they are,” Clarke says. Overseas, some domesticated rats are even registered as emotional support animals. “They are just really in tune with human emotions. They know when you are going through something and they will cuddle you,” she explains. “They are super great companions, they are really smart, they are really surprisingly clean as well – mine are all litter trained.”

At the moment, Clarke is enjoying the newfound attention on her rats, courtesy of RATs. “I’m happy to spread the word about rats and the fact that they are actually pretty amazing pets and companions. I don’t think I could ever go back to dogs and cats, feeling the way I do about rats.” She tells me that she recently had to come home sick from work and told her fiance she would need to take a RAT. On arrival home, he handed her one of her favourite rats, and then quickly took it back for assessment.

“Well, the test results look positive,” he said. “You have a 100% chance of cuddles today.” Her RAT, on the other hand, was thankfully negative.

Pet Week is proudly presented by our friends at Animates. For more Pet Week content keep an eye on The Spinoff and watch The Project, 7pm weeknights on Three.