While attention has been focused on the Treaty Principles Bill, the government has quietly begun reviewing Treaty of Waitangi clauses in 28 pieces of legislation – a move that could have consequences beyond Māori-Crown relations.

The key to being a good politician magician is misdirection – artfully guiding the audience’s attention away from where the magician doesn’t want them to look. A good magician excels at controlling what the audience sees, hears and focuses on, allowing them to perform seemingly impossible feats right in front of viewers’ eyes. It’s a combination of sleight of hand, storytelling and psychological manipulation.

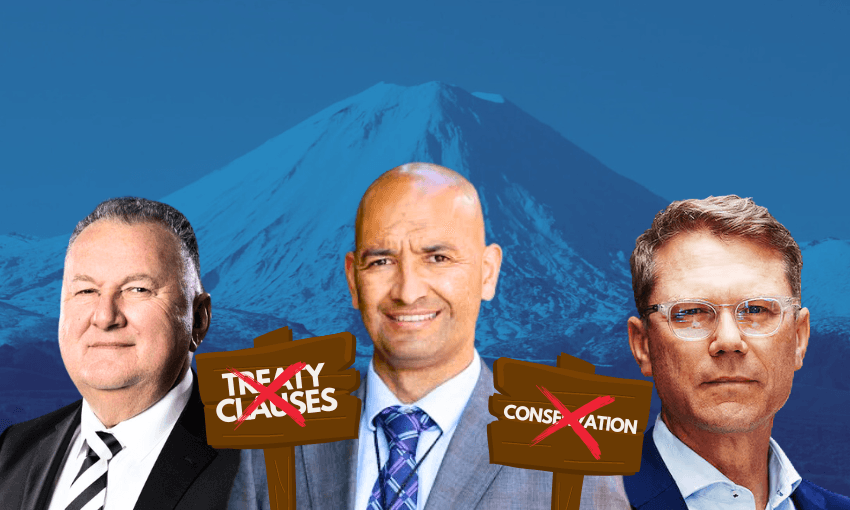

While Māordom has been in an uproar about the Treaty Principles Bill, which New Zealand First MP Shane Jones says is “dead in the water”, the coalition government has quietly set the wheels in motion for at least 28 pieces of legislation to have their Treaty clauses reviewed and potentially removed.

“Seymour gets this [Treaty Principles] bill. Winston Peters and New Zealand First get their review of all of the Treaty clauses in legislation – that might have far more substantive impacts, but it’s flown totally under the radar,” Ben Thomas, director of government relations and communications firm Capital, recently told Gone By Lunchtime listeners.

A review of all Treaty clauses in legislation, apart from Treaty settlements, was a part of New Zealand First’s coalition deal with National. The agreement states that the coalition will: “Conduct a comprehensive review of all legislation (except when it is related to, or substantive to, existing full and final Treaty settlements) that includes ‘The Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi’ and replace all such references with specific words relating to the relevance and application of the Treaty, or repeal the references.”

Jones has publicly maintained the key reason for the review is to remove ambiguity and confusion caused by the inclusion of generic Treaty references in legislation. There are around 50 pieces of legislation that include some reference to the Treaty of Waitangi, and Cabinet has identified 28 of them for review. However, speaking exclusively to The Spinoff, Jones revealed that he was particularly interested in reviewing section four of the Conservation Act, which requires anyone working under the act to give effect to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi when interpreting or administering anything under the act.

“I’ve found as the regional development minister that particular legislation has been very problematic because there’s a set of expectations within the local tangata whenua community around what the Department of Conservation’s obligations are when issuing concessions,” says Jones.

The partnership between iwi and the Department of Conservation (DOC) is central in effectively managing New Zealand’s natural environment. A recent Supreme Court case, Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki Tribal Trust v Minister of Conservation, set a precedent for how the department should interpret and apply section four, ruling that iwi preferences and potential economic benefits must be considered when granting concessions (ie permits or licences to carry out certain activity) on conservation land. This strengthens the role of the Treaty in conservation decisions.

The ruling was significant for iwi, establishing new guidelines for DOC to follow and ensuring that the Treaty principles would be given substantial consideration in future decision-making. The judgment built on previous legal cases such as the “Whales Case” and has had national implications for how the department engages with iwi, particularly around commercial opportunities on public conservation lands. While the Ngāi Tai case did not grant iwi veto powers, or exclusive rights over concessions in their rohe, it did find that the department should consider preference and potential economic benefits for iwi when granting concessions.

“We need to ensure that concessions and rights that business investors need in order to profit from the conservation estate are not frustrated through section four obligations that may have arisen because of various legal interpretations,” Jones says. “Consultation is one thing, but the power of veto, in my view, is a step too far.”

A specific example of the concessions process affecting investor confidence is the ongoing case of the Whakapapa ski field at Mount Ruapehu, which received around $20m in bailouts from the government, following issues with the granting of concessions by the Department of Conservation due to its section four obligations. According to Jones, a host of investors are uncertain about investing in businesses on the conservation estate because of the risk of a long-term concession not being granted.

“I think none of us are happy with how the process turned out in relation to the ski field investments at Ruapehu maunga,” says Jones.

“Projects are brought to my attention for funding purposes from various investors who feel that section four is a major handbrake in terms of economic development… often they’re talking with iwi or hapū who don’t want a long-term concession because they fear that it might represent alienation.”

It’s not just operating ski fields – another activity with a much higher potential environmental impact has been in the spotlight recently, after infrastructure minister Chris Bishop failed to rule out new mining activity on conservation lands. Combined with the Fast-track Approvals Bill, the removal of Treaty obligations under section four of the Conservation Act could open up the conservation estate for a raft of activities, including mining.

“We’re going to work very closely with Minister Tama Potaka to ensure that the way in which section four of the Conservation Act is administered does not thwart economic development and does not undermine investment,” says Jones.

The review of Treaty clauses actually began under the previous government, which established the Treaty Provisions Oversight Group in 2021. Led by Te Arawhiti: the Office for Māori Crown Relations, the group also includes Te Puni Kōkiri: the Ministry of Māori Development, the Ministry of Justice, Crown Law and law-drafters the Parliamentary Counsel Office. The group was formed to act as a committee of final approval for Treaty clauses in new legislation, following advice that an inconsistent approach to the clauses had created unnecessary risks, including potentially damaging the government’s relations with iwi. However, with no new “generic, open-ended Treaty clauses” expected to be included in any of the current government’s legislation, the current scope of work of the Treaty Provisions Oversight Group remains unknown.

In 2022, Te Arawhiti released a paper titled Providing for the Treaty of Waitangi in Legislation and Supporting Policy Design, which sought to guide policy-makers in when and how to include the Treaty in legislation. Despite the work that had gone into producing the 20-page document, Jones was uncertain it would be given much consideration throughout the new review process, which will be led by Treaty negotiations minister Paul Goldsmith, Te Arawhiti minister Tama Potaka, and New Zealand First.

“This time around, the mandate for the work comes from the coalition agreement… I wouldn’t suggest that our government’s going to follow any of the dictates that Jacinda Ardern put in place. We’re not in the Jacinda Ardern government,” says Jones.

“New Zealand First will be integrally involved because we need to ensure that the body of work which Cabinet addresses passes muster with what we put in place via the coalition agreement.”

As part of its review of the proposed Treaty Principles Bill, the Waitangi Tribunal also reported on the Treaty clause review, recommending it be put on hold while it was “re-conceptualised through collaboration and co-design engagement with Māori”. The tribunal report identified concerns that indigenous rights would be eroded through the removal of the clauses, and Ministry of Justice officials warned it would “have a detrimental effect on Māori-Crown relations”, but Jones disagrees.

“The existence of a Treaty reference in a piece of legislation doesn’t necessarily translate into a particular right. I think rights need to be respected where they’re subject to a Treaty of Waitangi full and final settlement but if the Treaty of Waitangi, for example, is in the Disabilities Act, what does that actually mean? Does that give whānau Māori a higher entitlement for disability services beyond other New Zealanders? That can’t possibly be right? What does it mean? No one’s able to tell me.”

The government has a complex and delicate balancing act on its hands. While Shane Jones and New Zealand First push for clarity and consistency in Treaty-related obligations, critics warn that the removal of these clauses could undermine the hard-fought recognition of iwi partnerships. As New Zealand navigates these waters, the future of legislation involving the Treaty of Waitangi could play a crucial role in shaping not only Māori-Crown relations, but the country’s commitment to equity, economic development and conservation.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.