Summer reissue: Adopted in 1834 the first national flag of New Zealand (Te Kara o Te Whakaminenga o Ngā Hapū o Nu Tīreni) symbolises more than just necessity – it represents Māori autonomy and a legacy of self-determination that continues today.

The Spinoff needs to double the number of paying members we have to continue telling these kinds of stories. Please read our open letter and sign up to be a member today.

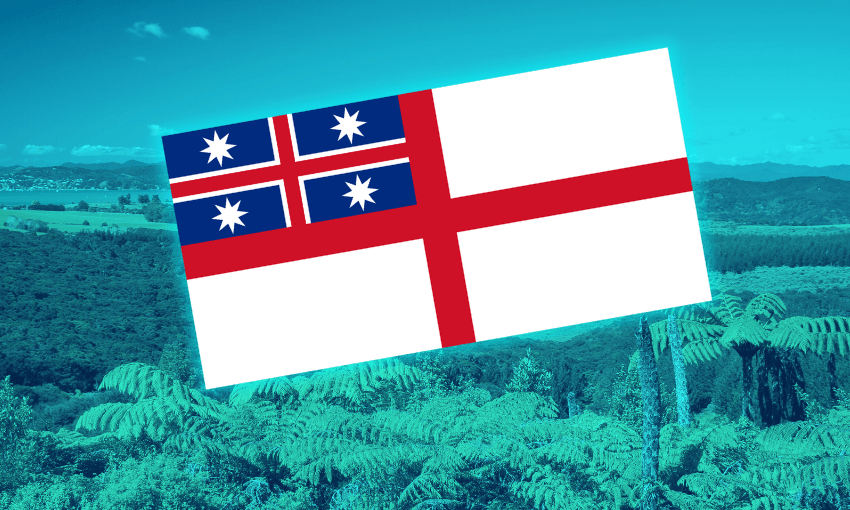

If you’ve ever ventured into the Far North, chances are you’ve probably seen a flag flying somewhere that sort of looks like the English flag, but with four white stars in the top left corner. It’s Te Kara o Te Whakaminenga o Ngā Hapū o Nu Tīreni – The Flag of the United Tribes of New Zealand, or Te Kara for short. It’s one of the most significant symbols in our country’s history, the first ever official flag of Aotearoa, and remains a symbol of mana motuhake for Māori across Aoteraoa, particularly in Te Tai Tokerau.

Te Kara represents the first formal declaration of New Zealand as a distinct nation-state, before te Tiriti o Waitangi and the establishment of colonial governance in Aotearoa. Understanding the origins, purpose, and legacy of this flag offers insight into the mana motuhake and rangatiratanga of hapū during a period of immense change in the early 19th century.

The origins of a flag

In the early 1800s, Aotearoa was being visited by an increasing number of European traders, whalers, and missionaries. Māori were networking and trading around Australia and the Pacific and travelling as far afield as Britain and North and South America by the mid-1800s. However, the country and its people lacked a formalised nation-state status, which created a legal and diplomatic problem – ships built in Aotearoa were not recognised under international maritime law, which required vessels to sail under a recognised national flag. This meant ships owned by Māori and Pākehā traders were vulnerable to seizure and faced difficulties entering foreign ports.

This issue apparently came to a head in 1830 when the trading ship Sir George Murray, built in the Hokianga, was seized in Port Jackson, Sydney, due to its lack of a flag representing a recognised sovereign nation (some claim the ship was seized due to financial issues). The British Resident in New Zealand, James Busby, recognising the growing importance of New Zealand in international trade and the threat this posed to Māori and Pākehā interests, looked to address the issue.

The adoption of Te Kara

In 1834, Busby convened a gathering of rangatira from various northern iwi, representing Te Whakaminenga o Ngā Hapū o Nu Tīreni, also known as the Confederation of United Tribes of New Zealand. Te Whakaminenga had been meeting around Northland since as early as 1808 to work collectively and manage their relationships with Pākehā.

Busby presented three flag designs to the rangatira, all designed by British naval officials. After deliberation, the rangatira selected the design that became known as Te Kara o Te Whakaminenga o Ngā Hapū o Nu Tīreni. The chosen flag featured a red St. George’s Cross on a white background, with a smaller red cross in the top left quarter, and four stars on a blue field. These stars represented the Southern Cross, a symbol of the Pacific and Māori connection to the land and sea.

On March 20, 1834, at a formal ceremony in Waitangi, the rangatira officially adopted the flag. The event was marked by a 21-gun salute, and the new flag was hoisted on a flagpole, symbolising Māori unity and New Zealand’s entry into international relations. The adoption of the flag was officially recognised by the British government, effectively acknowledging New Zealand as a distinct entity in international law. This was a crucial step towards the assertion of mana motuhake.

Te Kara is rich with both Māori and European symbolism, reflecting the convergence of Māori and European worlds during this period. The St. George’s Cross signifies the British influence, while the blue field and stars represent the Pacific and Māori cosmology. The combination of these elements is significant as it reflects a Māori decision to engage with Pākehā international systems while retaining distinct Māori identity and mana.

The flag was more than a solution to a maritime issue – it was also a symbol of the political aspirations of te Whakaminenga. The Confederation was an early attempt by Māori to present a unified front to the outside world, emphasising their rangatiratanga and mana motuhake. The adoption of Te Kara demonstrated that Māori sought to engage with global powers on their own terms, exercising mana over their whenua and people.

On October 28, 1835, te Whakaminenga further asserted its mana motuhake by issuing He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tīreni. Signed by 52 rangatira, He Whakaputanga stated that all sovereign power and authority in Aotearoa resided in the hands of the chiefs in their collective capacity. He Whakaputanga reinforced the symbolic role of Te Kara as a marker of nationhood and Māori independence.

Te Kara and te Tiriti o Waitangi

The significance of Te Kara took grew with the signing of te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840. Many rangatira saw te Tiriti as a formal continuation of the relationship established by He Whakaputanga and the adoption of Te Kara. While te Tiriti introduced British sovereignty, many chiefs believed that it did so in a way that preserved Māori autonomy, as the flag had signified.

As we know, interpretation of te Tiriti has been a constant source of debate, with many arguing the promises of Māori sovereignty were not upheld. In this light, Te Kara remains a powerful reminder of the political aspirations and rights of Māori, symbolising the inherent rangatiratanga promised to them.

Today, Te Kara o Te Whakaminenga o Ngā Hapū o Nu Tīreni remains a strong symbol of mana motuhake and rangatiratanga. It continues to be flown at Māori gatherings and events, particularly those focused on issues of Māori rights and governance. It’s also printed on T-shirts and hoodies, and stitched on vests my sovereigntist uncles wear. It has been embraced by various Māori political movements as a symbol of the ongoing struggle for recognition and sovereignty.

For many Māori, Te Kara is also a reminder of the promises made under He Whakaputanga and the te Tiriti – promises that remain unfulfilled in the eyes of many. Its continued use and prominence underscores the enduring relevance of the principles of mana motuhake, collective governance, and indigenous rights.

Te Kara o Te Whakaminenga o Ngā Hapū o Nu Tīreni is more than a historical artefact – it is a living symbol of the complex and evolving relationship between Māori and the Crown. Its adoption in 1834 marked a significant moment in the assertion of Māori nationhood and sovereignty, a legacy that lives on today. As a symbol, it speaks to the lasting strength of Māori identity, the ongoing fight for rangatiratanga, and the resilience of Māori governance in the face of colonial pressures. Its significance in Aotearoa history is profound, serving as a reminder of the nation’s bicultural foundations and the uncompromising mana of Māori.

First published October 28, 2024.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded by NZ On Air.