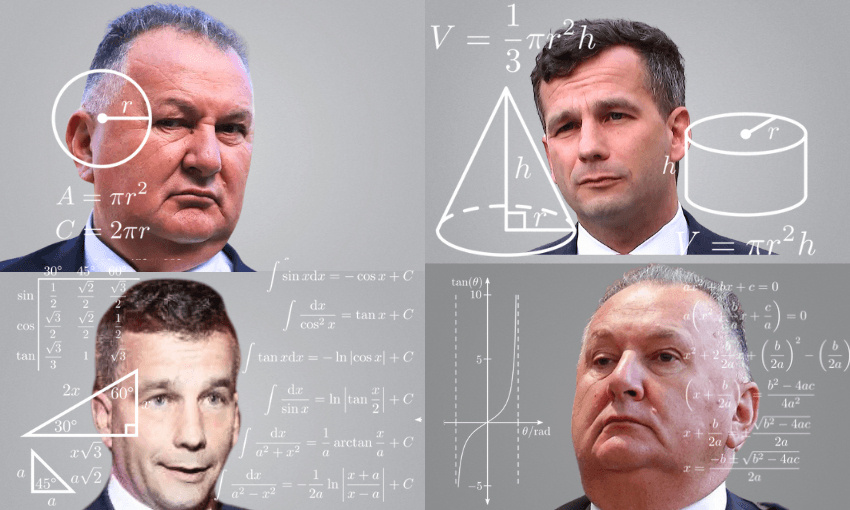

Despite decades of legal clarity, David Seymour and Shane Jones are claiming the principles are ambiguous in order to justify their push to undermine them, argues Māori legal scholar Carwyn Jones.

The government seems determined to pretend that the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi are currently unknown and unknowable. Despite nearly 50 years of reports from the Waitangi Tribunal and nearly 40 years of case law on the subject from our senior courts, the politicians would have you believe that Treaty principles are a source of great legal uncertainty. Nothing could be further from the truth.

David Seymour says we need to define “the principles of the Treaty” in legislation to have certainty, yet provides no evidence of the alleged current uncertainty. In fact, the regulatory impact statement prepared by the Ministry of Justice makes it clear that Seymour’s proposed Treaty Principles Bill would be less certain than the current situation, noting “the status quo also provides a higher degree of certainty about what the Treaty principles are and how they operate in New Zealand law”.

Shane Jones, meanwhile, tells us that we need to review, amend or replace Treaty principles provisions in 28 pieces of legislation in order to clarify their meaning and application. Jones (no relation, I hasten to add) chose an interesting example to illustrate his point. He was recently reported as saying: “…if the Treaty of Waitangi, for example, is in the Disabilities Act, what does that actually mean? Does that give whānau Māori a higher entitlement for disability services beyond other New Zealanders? That can’t possibly be right? What does it mean? No one’s able to tell me.”

Now, let’s start with the fact that there is no such thing as the Disabilities Act. I would concede that it is difficult to determine how Treaty principles would apply in an imaginary statute. But let’s assume the minister was intending to refer to the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2000. Sure, that law is no longer in force, after having been repealed by the Pae Ora (Health Futures) Act 2022, but at least the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act was at least once a real law and did contain a Treaty principles clause.

In fact, the reason that the minister may have been grasping for the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act is because its Treaty principles clause was much commented upon. That clause has been the subject of significant commentary because it did set out in detail how the Treaty principles provision was to operate in the context of the act.

Section 4 of that act stated: “In order to recognise and respect the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, and with a view to improving health outcomes for Maori, Part 3 provides for mechanisms to enable Maori to contribute to decision-making on, and to participate in the delivery of, health and disability services.”

The “Part 3” that is referred to contained the provisions relating to district health boards with clauses that specified exactly how Māori were enabled “to contribute to decision-making on, and to participate in the delivery of, health and disability services”. There was a direct and explicit link from the recognition of Treaty principles to the particulars of how they applied in the context of the act. All very straightforward.

If anything, the legislation that replaced the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act went into even greater detail about how Treaty principles would apply. The Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act contained a list of 14 particular requirements to provide for the Crown’s intention to give effect to the principles of the Treaty. Though some of these provisions (those relating to the Māori Health Authority) have themselves now been repealed, the Pae Ora Act still contains nine specific requirements, including that a permanent committee (the Hauora Māori Advisory Committee) be established to advise the minister, and that the Government Policy Statement contain priorities for hauora Māori.The current Treaty principles provision in that act also appears to be clear and specific.

Granted, some Treaty principles provisions are not as specific as that. Section 9 of the State-Owned Enterprises Act 1986 states: “Nothing in this Act shall permit the Crown to act in a manner that is inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi.” That is much broader and, in 1986, there may well have been some uncertainty as to how that clause would apply. But in 1987, the Court of Appeal made things very clear. In its decision in the famous New Zealand Māori Council v Attorney-General case, the court identified relevant principles of partnership, active protection and redress. The application of those principles, in that case, ultimately required the government to agree, with the New Zealand Māori Council, a mechanism to protect potential Māori interests in state-owned enterprise land before further steps were taken under the act. That was a specific application of Treaty principles to a specific context.

Every decision of the courts that has dealt with Treaty principles since that time has provided another specific application of those principles. We now have lots of examples of what Treaty principles mean and how they apply, even when the provision of the statute is broadly worded. This body of cases gives us a very settled and certain area of law.