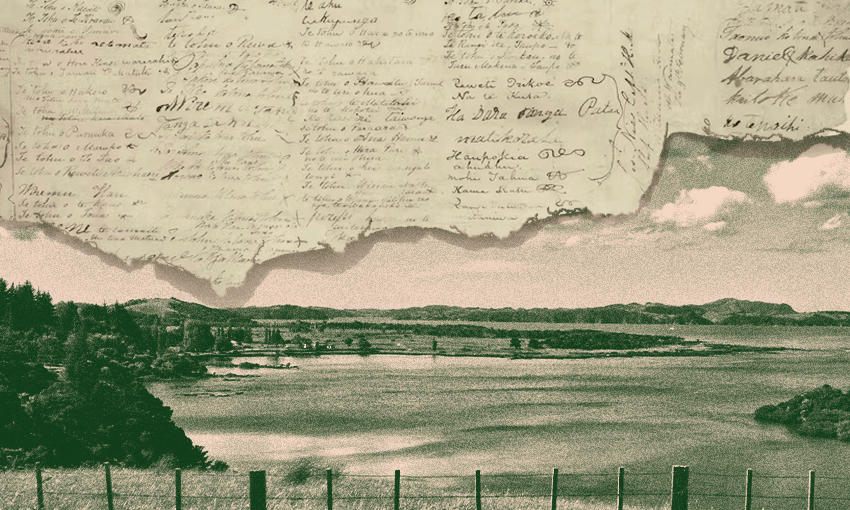

The Waitangi Tribunal has a broad remit, but it’s not new, writes Carwyn Jones in this handy explainer.

New Zealand First MP Shane Jones has raised concerns about the Waitangi Tribunal going beyond its remit by addressing contemporary issues including the planned inquiry into a possible new constitution. The coalition agreement between National and New Zealand First includes an agreement to “Amend the Waitangi Tribunal legislation to refocus the scope, purpose, and nature of its inquiries back to the original intent of that legislation”. The original intent of the Treaty of Waitangi Act was for the Tribunal to inquire into contemporary issues of Crown policy and practice. This is precisely the focus of the Tribunal’s current kaupapa inquiry programme.

The inception

The Waitangi Tribunal was established as a commission of inquiry by the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975. It inquires into claims of breaches of the principles of the Treaty, makes findings as to whether Crown actions are consistent with the principles of the Treaty and makes recommendations to the Crown for the practical application of those principles. The long title of the Treaty of Waitangi Act records that it is “An Act to provide for the observance, and confirmation, of the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi by establishing a Tribunal to make recommendations on claims relating to the practical application of the Treaty and to determine whether certain matters are inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty.”

The Treaty of Waitangi Act does not define what the principles of the Treaty are but requires the Tribunal to consider both the English text and Māori text of the Treaty in carrying out its functions. For the purposes of the Act, the Waitangi Tribunal has “exclusive authority to determine the meaning and effect of the Treaty as embodied in the 2 texts and to decide issues raised by the differences between them”. The Tribunal has applied principles such as partnership, active protection, equity, and equal treatment.

For a claim to be registered with the Tribunal, it must meet four criteria:

- The claim must be made by a Māori person (on behalf of themselves or a broader group);

- It must relate to some Crown action or omission;

- There must be an allegation that the Crown act or omission is in breach of the principles of the Treaty; and

- The claim must allege that the claimant or claimant group is prejudicially affected by that breach.

If a claim meets those criteria, there are only limited circumstances in which the Tribunal can refuse to inquire into it. The Tribunal is prohibited from inquiring into claims relating to private land or matters which have already been the subject of a settlement. The Tribunal may decline to inquire into claims which it determines are frivolous or vexatious. As a commission of inquiry, the Tribunal is largely able to set its own process and procedures.

The concerns

Claimants have sometimes been frustrated by the length of time that it takes for the Tribunal to inquire into and report on claims. With the establishment of the Treaty settlement process, the Tribunal aimed to deliver the style of report the claimants required to engage in direct negotiation with the Crown, rather than the more detailed and comprehensive findings and recommendations produced in earlier inquiries. Now, claims are grouped thematically as part of the kaupapa inquiry programme.

Inquiries are heard by panels of Tribunal members who have knowledge and experience in fields such as law, history, Te Ao Māori, business, and public policy. Members are appointed on the recommendation of the Minister of Māori Affairs on the basis of their knowledge and personal attributes and with “regard to the partnership between the two parties to the Treaty” (which has generally been taken to mean that the membership of the Tribunal should be comprised of Tangata Whenua and Tangata Tiriti).

The scope and its evolution

When the Treaty of Waitangi Act was enacted in 1975, the Waitangi Tribunal did not have jurisdiction to inquire into historical claims. At that time, it could only examine actions taken by the Crown (or continuing) after the Act came into force, that is, from 1975 onwards. The Tribunal’s original jurisdiction was, therefore, specifically focused on contemporary law, policy, and practice.

In 1985, the Treaty of Waitangi Act was amended to enable the Tribunal to inquire into claims relating to Crown actions going back to the signing of Te Tiriti in 1840. This covered the period in which large scale land alienation took place in breach of the guarantees in Te Tiriti and these historical claims became a central focus of the Tribunal’s work for a number of years. However, the Tribunal always retained its original jurisdiction to inquire into claims relating to contemporary law and policy and, as early as the 1970s and 1980s, the Tribunal heard important claims relating to fisheries regulations, te reo Māori, and of contemporary environmental issues. Significant claims have also been heard in relation to intellectual property and traditional knowledge, policy proposals in relation to the foreshore and seabed, and prisoner voting rights, amongst a host of other contemporary policy issues.

In 2006, the Treaty of Waitangi Act was amended again so that from 2008 onwards the Tribunal could no longer receive any new claims that related to historical Crown action. Historical claims are defined as those claims which relate to Crown acts or omissions that took place before September 21, 1992. That date is chosen as effectively representing the beginning of the modern Treaty settlement process as it was the date at which Cabinet, in the context of the settlement of commercial fishing claims (in what became known as “the Sealord deal”), approved principles for the settlement of historical claims. The Tribunal is still completing some of its historical inquiries but its focus is now returning to its original jurisdiction of contemporary claims, which it is addressing through a programme of thematic or kaupapa inquiries.

The kaupapa inquiries and recommendations

The Tribunal has begun kaupapa inquiries into a range of topics including health services and outcomes, housing policy and services, the justice system, fresh water and geothermal resources, mana wāhine, and constitutional claims. The Tribunal has already reported on the first stages of some of these inquiries. For example, the report on Stage One of the Health Services and Outcomes Kaupapa Inquiry was published in 2019 and recommended, among other things, that the Crown explore establishing a stand-alone Māori primary health authority.

The establishment of an independent Māori health authority was one recommendation that was taken up by the Crown, though, of course, will be disestablished by the new government. But the Crown is not obliged to follow the Waitangi Tribunal’s recommendations. The only binding powers that the Waitangi Tribunal has is in relation to Crown Forest License land or former State-owned Enterprise land. These powers were granted to the Tribunal following specific agreements between the Crown and the New Zealand Māori Council in the 1980s and they have never been fully exercised by the Tribunal.

Otherwise, the Tribunal makes recommendations to the Crown that the Crown can choose to accept or reject or ignore. For example, the recommendations to make Māori an official language and create a Māori language commission were adopted, whereas the recommendation that the Government abandon its policy in relation to the foreshore and seabed in 2003 was, emphatically, not taken up.

It is also important to note that the Tribunal cannot constrain the legislative function of Parliament. In fact, the Tribunal is prohibited from hearing claims relating to matters that are the subject of bills before parliament, unless such a bill is specifically referred to the Tribunal by the house of representatives, which has never happened. So, there is no possibility for the Tribunal’s findings or recommendations on constitutional or any other matters to usurp the role of parliament. The Tribunal is a statutory body – it was created by parliament and its jurisdiction is set by parliament and can be amended by parliament, as it has happened a number of times since 1975.